the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Eco-morphological changes and potential salmon habitat suitability since pre-industrial times in the Mulde River system (Germany)

Martin Offermann

Michael Hein

Ronja Hegemann

Kay Gödecke

Lucas Hegner

Yamuna Henke

Nele Schäfer

Hanna Shelukhina

Erik Liebscher

Severin Opel

Johannes Rabiger-Völlmer

Lukas Werther

Christoph Zielhofer

Offermann, M., Hein, M., Hegemann, R., Gödecke, K., Hegner, L., Henke, Y., Schäfer, N., Shelukhina, H., Liebscher, E., Opel, S., Rabiger-Völlmer, J., Werther, L., and Zielhofer, C.: Eco-morphological changes and potential salmon habitat suitability since pre-industrial times in the Mulde River system (Germany), E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 74, 325–354, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-74-325-2025, 2025.

Channel patterns and river connectivity are widely recognised to be representative parameters for the fluvial–geomorphological behaviour and the eco-morphological properties of rivers. They are sensitive to climate and land-use changes and, in turn, can indicate the habitat suitability for aquatic fauna, i.e. expressed by the diversity of channel width, flow velocity, and depositional regimes. Both habitat potential and the overall river connectivity since medieval times have also been influenced by barriers such as weirs and dams. Here we present the results of a multi-temporal study investigating river morphology, river connectivity, and floodplain land use in the Mulde River system. The study is motivated by the local extinction of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) within the last 2 centuries and reintroduction endeavours that have met with very limited success. In order to test for salmon presence in relation to waterbody structures, we make use of old maps (Sächsische Meilenblätter, 1780–1821; Von Deckersche Quadratmeilenblätter, 1816–1821) to pinpoint (i) historical barriers and (ii) anthropogenic changes in channel patterns that may have affected migratory fish populations. Furthermore, we evaluate (iii) historical floodplain land use as a pollution proxy, presuming that this also influences salmon habitat suitability. Our initial results point to a negative relation between an increasing number of cumulative barriers, as well as increased floodplain land use, and the presence of salmon populations during past periods. Finally, sinuous and meandering channel patterns correspond to higher probabilities of salmon presence.

Gerinnebettmuster und freier Wasserfluss sind wichtige Parameter für die Gewässerstruktur und damit verknüpfte ökomorphologische Eigenschaften von Flüssen. Beide Parameter sind empfindlich gegenüber Klima- und Landnutzungsänderungen und geben wiederum Aufschluss über die Qualität des Flusshabitats für die aquatische Fauna, ausgedrückt beispielsweise über die Breitendiversität des Flussbettes, Fliessgeschwindigkeit und fluviale Ablagerungsregime. Sowohl das Gerinnebettmuster als auch freier Wasserfluss wurden seit dem Mittelalter durch Barrieren wie Wehre und Dämme beeinflusst. Hier präsentieren wir die Ergebnisse einer multitemporalen Studie, die Flussgerinnemuster, freien Wasserfluss und die Landnutzung in den Auenräumen der Mulde und ihrer Zuflüsse untersucht. Anlass für die Studie ist das Aussterben des Atlantischen Lachses (Salmo salar) innerhalb des Zeitraums der letzten zweihundert Jahre und die nur sehr begrenzt erfolgreichen Wiederansiedlungsprogramme. Um das Vorkommen von Lachsen in Bezug auf die Gewässerstruktur zu untersuchen, verwenden wir Informationen aus Altkarten (Sächsische Meilenblätter, 1780–1821; Von Deckersche Quadratmeilenblätter, 1816–1821). Hierbei werden (i) historische Barrieren und (ii) anthropogene Veränderungen des Gerinnebettmusters identifiziert und verortet, denn diese hatten möglicherweise Auswirkungen auf die Ausdehnung des Lebensraumes der Wanderfische. Darüber hinaus bewerten wir (iii) die Intensität der historischen Landnutzung in Auenräumen als Zeigerwert für die potentielle Flussverschmutzung, da wir davon ausgehen, dass diese die Lebensraumqualität der Lachse erheblich beeinflusst hat. Erste Ergebnisse deuten auf einen gegenläufigen Zusammenhang zwischen zunehmender Anzahl aufsummierter Barrieren und erhöhter Landnutzungsintensität in der Aue einerseits und dem Vorkommen von historischen Lachsbeständen andererseits. Schließlich korrespondieren die früher natürlich gewundenen und mäandrierenden Flussläufe mit einer höheren Wahrscheinlichkeit an historischen Lachsvorkommen.

- Article

(19817 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(453 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

1.1 Eco-hydrological downturn in rivers

The fauna associated with rivers has been hit particularly hard by the global biodiversity crisis. Migratory fish populations in particular are among the species most affected by a decline in biodiversity worldwide (He et al., 2019; Sayer et al., 2025). Even before the major river regulations of modern times, people intervened in river structures and floodplains in order to adapt them to their needs. For the purposes of transport, hydropower, and food and water supply, artificial features were installed, for example, in the form of bridges, weirs, and locks, as well as hydraulic engineering measures such as bank reinforcements or dikes (Holbach and Selzer, 2020; Mauch and Zeller, 2008). The hydraulic connectivity of the rivers was increasingly reduced in pre-industrial times, and, in addition, pollution and overfishing often led to a significant decline in migratory fish populations (Bartosiewicz et al., 2008; Galik et al., 2015; Haidvogl et al., 2015).

1.2 Salmon habitat suitability and waterbody structure

Salmon populations are affected by river connectivity and habitat suitability. Depending on their life stage, salmon have different habitat requirements (Füllner et al., 2004a): for example, for spawning, they require a gravel bed (Geist and Dauble, 1998). Salmon eggs have a long development period (approx. 180 d) and, during this time, are sensitive to changes in bed shear stress or shear forces that can be caused by floods (MUNLV, 2006). This effect can be intensified by anthropogenic river straightening or by severe incision (Aruga et al., 2023). Straightening in particular prevents the self-regulation of the watercourse during floods (Newson and Newson, 2000). Young salmon prefer waters with a low proportion of fine sediment. An excess of fine-grained sediments may clog the spaces between pebbles and boulders, thus reducing the availability of hiding places in their nursery habitats (Armstrong et al., 2003). Increased sediment mobilisation, e.g. through increased flow velocities, is unfavourable at this stage. The yolk sac larvae of the salmon require riffles for their development. These are shallow sections with turbulent currents. Even at high water, young salmon like to move into shallow water at the edge of rivers. If these areas are missing, e.g. in deeply incised rivers or in areas that have been anthropogenically straightened or dammed, this is also unfavourable for the establishment of salmon. From the final freshwater (parr) stage onwards, salmon prefer deeper, stronger-flowing areas. It is important that a river has all of these diverse areas downstream (Armstrong et al., 2003), but the distance between the individual areas must not be too high so that the larvae can still reach them (MUNLV, 2006). Later in the life cycle, when adult salmon are ascending upstream to spawn, they wait in deep pools for the onset of spawning maturity.

Geologically induced narrowing of the river cross-section or abrupt changes in gradient lead to abrupt changes in flow conditions (laminar or turbulent) and increased erosion capacity. However, human-induced barriers such as weirs can also have this effect (Downward and Skinner, 2005; Fehér et al., 2014; He et al., 2024; Meybeck and Vörösmarty, 2005). Therefore, artificial changes in the river morphology disturb the balance of the natural interplay of the riverbed characteristics, cross-sectional profile, ground plan pattern, and bed gradient that functions as the self-regulation process in fluvial systems.

The longitudinal richness and heterogeneity of waterbody structure therefore have a direct impact on migratory fish populations. These features regulate flow velocities, riffle–pool distributions, riverbed substrates, and access to thermal refuges, with the latter preventing heat stress (Dugdale et al., 2015; Ebersole et al., 2003). The construction of barriers and river embankments and the homogenisation of discharge (Clavero and Hermoso, 2015; He et al., 2024) have, accordingly, reduced riverine structural diversity. To mitigate this development, the EU formulated the European Water Framework Directive as a political instrument facilitating both the documentation and improvement of habitat suitability and river connectivity. In general, it aims to restore and maintain a good physico-chemical condition of all EU-wide ground and surface waterbodies (Hering et al., 2010), which is one of the preconditions for a good ecological status of rivers. The operational analysis method for this is the assessment of waterbody structure based on on-site surveys and map evaluation (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999).

1.3 River pollution and its effects on salmon populations

Apart from their specific structural habitat requirements, salmon react most sensitively to the chemical water quality. Juvenile salmon imprint on the chemical and olfactory signature of their natal river, thus providing the adult fish with an orientation cue during their upstream migration for spawning (Bett et al., 2016). Changes in the chemical composition of the river water might lead to a confusion of this homing mechanism and an avoidance of the natal river (Saunders and Sprague, 1967). Furthermore, exposure to river pollutants such as heavy metals (e.g. from mining activity) and organic contaminants (e.g. from agricultural practices and municipal and industrial effluents), even in fairly low (i.e. sublethal) concentrations, poses a threat to the livelihood of salmons in multiple ways. The chief impacts are growth impairment and disruption of the sensory system, as well as reduced predator avoidance and reproduction rates (Cobelo-García et al., 2017; Dubé et al., 2005; Hecht et al., 2007; Morán et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2013; Sauliutė and Svecevičius, 2017). In addition, organic pollutants and nutrient inputs may cause the depletion of oxygen in the water, another parameter of which salmon have particular requirements (Armstrong et al., 2003; Manitcharoen et al., 2020; Sánchez et al., 2007).

1.4 Historical perspective on the eco-hydrological downturn of rivers

The impact pattern of fluvial–geomorphological habitat suitability and pollution on migratory fish populations can be understood from an actualistic perspective. However, not much is yet known about how human influence has affected habitat suitability and pollution and, therefore, also migratory fish populations in the past. Such knowledge is important in order to better understand the current reintroduction projects and possible setbacks. What is the baseline of the natural river habitat and how have disturbances developed over time in river systems on the way to the fluvial anthroposphere (Werther et al., 2021)?

In order to identify the pre-industrial baseline of the waterbody structure, it is advisable to reconstruct the historical channel pattern of pre-industrial rivers using old maps, which are often the sole source of exploitable information for spatially explicit reconstructions (Hohensinner et al. 2021; Witkowski, 2021).

In order to assess the potential for historical river pollution in floodplains, the reconstruction of historical floodplain land use is an initial proxy. Agronomic and other intensive forms of land use in floodplains have direct consequences on nutrient inputs into rivers (Krause et al., 2008), and they also act as a source of suspended river sediment (Yu and Rhoads, 2018), with adverse effects on the spawning success and juvenile vitality of salmon (Armstrong et al., 2003). Urban and industrial development and crafts and manufacturing in the floodplain result in the discharge of residential and commercial wastewater (Derx et al., 2016; Español et al., 2017; Lyubimova et al., 2016). Historical mining activities in particular have a significant influence on pollutant input into rivers, especially in low mountain river catchments (Mills et al., 2014; Resongles et al., 2014). While the mines themselves are usually located outside the floodplain, secondary structures for ore processing, as well as spoil tips or mining settlements, are often positioned within the floodplain or at its margins (Cembrzyński, 2019; Derner et al., 2024; Knittel et al., 2005). Furthermore, flooded adits and shafts in former mining districts often have a direct connection to groundwater and/or surface waters in the floodplain (Bozau et al., 2017; Greif et al., 2008).

The populations of fish in the past, especially migratory fish, can be reconstructed in various ways, e.g. based on zoological remains (Schaal et al., 2020) biomolecular approaches such as sedimentary DNA (Brown et al., 2018), and written sources (Andreska and Hanel, 2015; Haidvogl et al., 2014). Because of the fishing rights reserved for the nobility and their associated cultural significance, migratory fish such as Atlantic salmon are often mentioned in archival records and early writings on modern natural history (Kentmann, 1549), as well as in more recent fishing reports (Füllner et al., 2004b; Wolter, 2015). Historical data on migratory fish can therefore be used as a proxy parameter for historical aquatic biodiversity (Winiwarter et al., 2013; Haidvogl et al., 2015). In the Elbe River, a main stem river system in central Europe, the long-term population decline of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) led to its extinction in the middle 20th century. After decades of the complete absence of salmon, the Saxonian state fishing authorities launched a reintroduction programme in the 1990s that is ongoing.

1.5 Aim of the study

- a.

In order to develop a pre-industrial baseline for and a basic understanding of historical river connectivity and migratory fish habitat suitability, this study aims to compile a systematic, quantitative dataset covering the spatial and temporal development of (i) channel patterns, (ii) floodplain land use, and (iii) barriers for the Mulde River system since the onset of the 19th century. For validation purposes, the acquired data will be evaluated in tandem with geological and historical information at a broad observational level. The Mulde River system is part of the Elbe River system and was selected for this pilot study due to its high diversity of natural channel patterns and the extensive anthropogenic interventions that date back to pre-industrial times. Floodplain land use serves as a proxy parameter for human impact and the corresponding potential for floodplain pollution.

- b.

In order to compare and validate eco-morphological data on historical waterbody structure and river connectivity with a biotic parameter referencing historical migratory fish dynamics, we use self-collected data on historical Atlantic salmon presence. This study constructs an initial open-access database on modern and historical salmon catches in the Mulde River main tributary system and the main stem, the Elbe River. The data acquired using secondary historical sources are spatialised by applying a semi-quantitative grid approach (Clavero and Hermoso, 2015; Zielhofer et al., 2022) and are subsequently compared with the historical eco-morphological parameters.

- c.

Finally, our goal is to carry out a critical assessment of the previous results and to highlight research perspectives for further development.

2.1 Catchment hydrology of the Mulde River

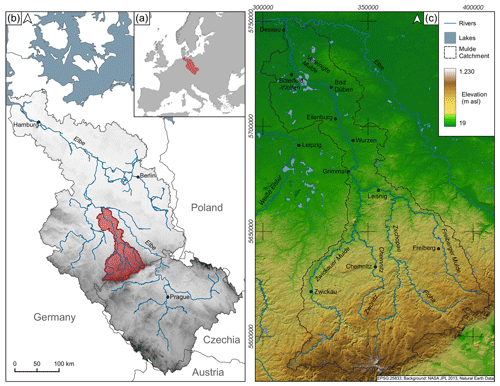

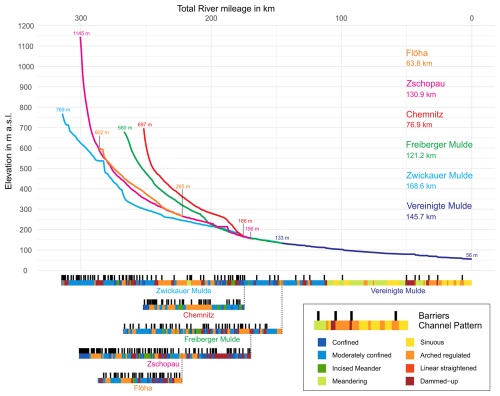

The Mulde River (Vereinigte Mulde), situated in eastern Germany, is among the largest tributaries within the Elbe River system (Fig. 1). It forms at the confluence of its branches, the Zwickauer and the Freiberger Mulde. Both of the latter and their major subordinate tributaries (e.g. Chemnitz, Zschopau) originate in the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge). The Mulde River flows through the Leipzig lowland basin (Decker, 2014) and, at Dessau-Roßlau, joins the Elbe River (Fig. 1). It has an overall catchment area of 7345 km2 and a length of 147 km (plus lengths of 167 and 124 km for the Zwickauer and Freiberger Mulde, respectively, before their confluence). From the headwaters to the mouth of the Mulde River, stream gradients range from ca. 14 % to 0.3 % (Otto and Mleinek, 1997). Its flow regime is dominated by snowmelt in the Ore Mountains so that discharge maxima usually occur in March–April, while minima occur in autumn. In deviating from this pattern, extreme flooding is more likely to happen in the summer season, when the mean discharge values of ca. 70 m3 s−1 can be exceeded many times over (e.g. approx. 2500 m3 s−1 in August 2002) (Vetter, 2011b).

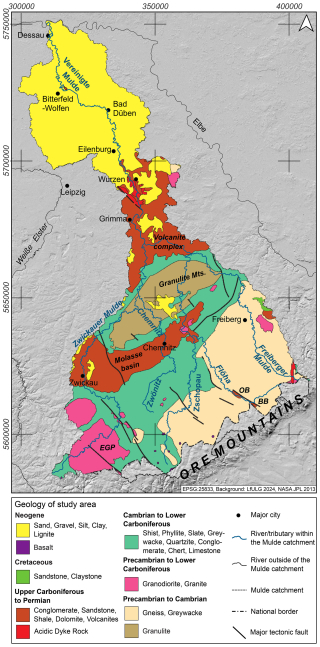

2.2 Geology and climate

The headwaters of the Mulde River system are located in the ridge area of the Ore Mountains (highest elevation: Klínovec, 1244 m a.s.l. (metres above sea level)). They were formed during the Variscan orogeny and mainly consist of Palaeozoic, highly metamorphic, and magmatic rocks (Ulrich, 2013). Structurally, the Molasse Basin (Erzgebirgsbecken), the Granulite Mountains, and the Saxonian Volcanite Complex are also a product of the Variscan orogeny or its direct after-effects and are dominated by conglomerates, granulite, and rhyolite, respectively (Fig. 2). After an applanation in the Permian, Neogene intra-plate tectonics affected the aforementioned units and created a fault block that was uplifted and tilted to the northwest. This resulted in a gently inclined low mountain area with rather uniform relief features apart from the varying incision depths of the river valleys (Wagenbreth and Steiner, 1990).

Figure 2Pre-Quaternary lithological map of the Mulde River catchment. EGP: Eibenstock Granite Pluton, OB: Olbernhau Basin, BB: Brandov Basin. Drawing: Martin Offermann and Michael Hein.

In the lower course north of Wurzen, the landscape is characterised by unconsolidated sediments from the Neogene (marine and fluvial deposits, lignites) and Quaternary (mainly glaciofluvial sands and glacial tills from the Elsterian and Saalian) (Eissmann, 2002a, b).

The Holocene floodplain of the Mulde River features gravel beds and fine-grained overbank deposits in the lower and middle courses. These overbank deposits have been largely supplied by historical and pre-historical land-use-driven soil erosion in the Ore Mountains and corresponding forelands (Vetter, 2011b; Tinapp et al., 2008, 2019; Ballasus et al., 2022; Derner et al., 2024).

The lower and middle reaches of the Mulde River are characterised by a lowland climate in the transition zone from temperate Cfb to cold Dfb Köppen climate (Peel et al., 2007). Precipitation values range from around 600–700 mm in the lower reaches to over 1000 mm at the headwaters, with average annual temperatures of 10 to 7 °C, respectively (Scholz et al., 2005).

2.3 Land use

The landscape of the Ore Mountains is predominantly characterised by forests. Along the Zwickauer Mulde River, however, there are various agricultural areas and isolated settlement areas (Mannsfeld and Syrbe, 2008). The situation is similar in the Freiberger Mulde catchment. To some extent, and in spite of reforestation measures since the 1800s, the forest–open-land distribution in these upper reaches still reflects the centuries-long intensive and timber-consuming mining activities in the Ore Mountains (Kaiser et al., 2023; Theuerkauf and Kaiser, 2024). Downstream, the agricultural utilisation of the landscape increases in the direction of the Leipzig Basin, where both rivers join. In the area of the Vereinigte Mulde River, there is a mixed land use of forests and fields (Mannsfeld and Syrbe, 2008). The region saw a relatively early onset and rapid progression of industrialisation in the 19th century. Therefore, the chemical water quality is heavily affected by agricultural, municipal, and industrial effluents, and the Mulde River was considered to be a highly polluted river from around 1900 to the 1990s (Otto and Mleinek, 1997).

3.1 Cartographic resources used in this study

In recent decades, multiple studies have been published on past waterbody parameters before river regulation programmes were implemented. The majority of them concentrate on particular river segments (Hohensinner et al., 2013; Schielein, 2010; Zielhofer et al., 2025). However, even at a broader regional scale, old maps are a promising tool for reconstructing historical waterbody structure, as has already been developed for historical channel patterns (Hohensinner et al., 2021; Witkowski, 2021).

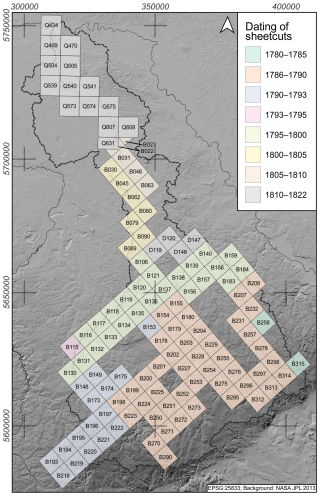

The oldest map series appropriate for this task in the study region, fulfilling the demand for both reliable geodetic surveying and extensive coverage, was produced in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. At that time, driven by military and administrative motives, German states ordered medium-scaled maps depicting their territories. In 1780, engineer major Friedrich Ludwig Aster was tasked with conducting a military topographical survey of Saxony based on a state-wide triangulation. The resulting map was later coined Sächsische Meilenblätter (Witschas, 2002). Three copies exist, two of which are used in this study. The original, which was heavily used and is now stored in Dresden, and the king's copy, which was transferred to Prussia in the aftermath of the Battle of the Nations (1813) and is well preserved. Most of the sheets in this study were mapped completed by 1806, and the last four sheets were mapped by 1821 (Fig. 3). Detailed metadata after Schmidt et al. (2024) are presented in Table S2 in the Supplement.

Each sheet measures one square cubit (one cubit corresponds to approximately 56.6 cm) and depicts one square mile (one mile corresponds to 12 000 Dresden cubits, which equates to approximately 6.8 km). The scale is therefore 1 : 12 000. The map content illustrates boundaries, road networks, waterbodies, woodland, and meadows. Even within the villages, houses are depicted individually. The relief is characterised by the use of graphically prominent Lehmann Mountain hachuring (Witschas, 2002). However, a legend explaining the map symbols and pattern fills is absent.

The downstream part of the Vereinigte Mulde River north of Gruna to Dessau-Roßlau is not covered by the Sächsische Meilenblätter because it was not mapped before its territorial loss to Prussia in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. For this section, we used the contemporaneous Von Deckersche Quadratmeilenblätter, mapped between 1816 and 1821 by Carl von Decker and Karl Ferdinand von Rau following von Decker's experiences in topographic mapping during the Napoleonic Wars (von Decker, 1816).

3.2 Selection of parameters for historical waterbody structure mapping

Waterbody structure mapping (Gewässerstrukturgütekartierung) is a procedure that was developed in accordance with the European Water Framework Directive (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999). It records the eco-morphologically relevant structural conditions of waterbodies required to be monitored for the directive. The initial basis for the assessment is the objective and consistently comprehensible identification of structural elements of the watercourse and its surroundings, employing a predefined parameter system for on-site inspections. These structural elements are referred to as individual parameters, which are especially relevant for the assessment of the ecological functionality of watercourses. Additionally, or as an alternative to detailed on-site mapping, data acquisition procedures also comprise quick map-based assessments for overviews (Übersichtskartierung). As this abridged overview mode is already optimised for map applications, we made use of it for retrieving information from the old map sections and from current topographic maps (DTK10, DTK25), as well for comparison purposes. According to their indicator function, six main parameter groups are constructed, namely course development, longitudinal profile, bed structure, transversal profile, bank structure, and water environment, which are subsequently divided into 25 individual parameters.

Figure 3Overview of old maps used for mapping historical channel patterns, floodplain land use, and barriers. Oblique orientation/alignment: Sächsische Meilenblätter (B: Berlin copy, D: Dresden copy); straight orientation/alignment: Von Deckersche Quadratmeilenblätter (Q).

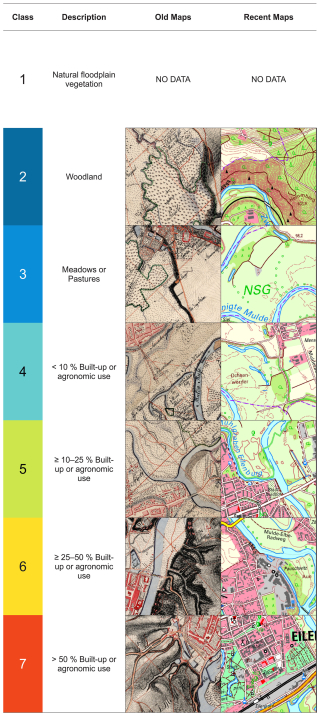

From these 25 individual parameters for waterbody structure mapping, we select 3 that might be relevant for salmon habitat suitability and, at the same time, are widely represented in historical cartographical material. The selected parameters are channel pattern (Sect. 3.3), proxying for substrate diversity, riffle–pool distributions, and spawning-habitat suitability (Geist and Dauble, 1998; Vetter, 2011b), as well as human impacts on natural river structures; floodplain land use (Sect. 3.4) as a proxy of human impact and pollution; and barriers (Sect. 3.5) as a proxy for river connectivity. Other potentially salmon-relevant parameters such as riverbed substrate composition, riverbed width variance, channel bars, special river course features (e.g. dead wood), and bank vegetation are omitted because they are not reliably mappable solely based on old maps.

All structural parameters are recorded using a standardised 1 km2 grid covering the entire Mulde River course and those of the main tributaries, Chemnitz–Zwönitz, Zschopau, and Flöha. Within the joint research programme DFG-SPP 2361 “On the Way to the Fluvial Anthroposphere” and the virtual research environment Spacialist, the grid approach is designed to facilitate data synthesis across heterogeneous sources such as written sources, old maps, and modern topographic maps with different spatial and chronological scales (Lang et al., 2020; Morrison et al., 2021; Werther et al., 2021; Zielhofer et al., 2022).

3.3 Channel patterns

Distinct fluvial channel patterns evolve from an interplay of multiple factors, such as discharge (variability), velocity, (suspended) sediment load, gradient, tectonic activity, and geology, and they also respond to climatic and land-use changes. The combination of these factors produces river styles with specific structural properties and diversities, e.g. regarding channel bars (Payne and Lapointe, 1997), stream width variance, and riffle–pool sequences. In this way, channel patterns are informative of the overall geomorphic and ecological functioning alike and can be used as an integral indicator of in-stream salmon habitat suitability and diversity (Brierley and Fryirs, 2004; Cianfrani et al., 2009; Moir et al., 2004; Stefankiv et al., 2019; Twidale, 2004). For classification, (i) the coherence of the streambed (single vs. multiple threads), (ii) the sinuosity, and (iii) lateral migration (or confinement) are among the most significant parameters. Usually, the single-thread types “straight” and “meandering” and the multi-threaded “anastomosing” and “braided” are distinguished, along with various transitional forms (Alabyan and Chalov, 1998; Vandenberghe, 2002). However, due to the inherently complex nature and geographic differences of river systems, no generally accepted definitions or naming conventions exist, though some have been proposed recently (Fryirs and Brierley, 2018).

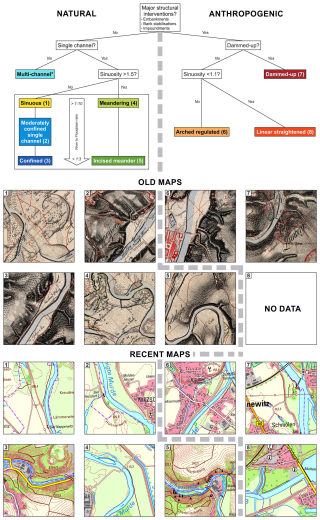

Here, we use the nomenclature and map-based approach applied by Hohensinner et al. (2021) for the comparative analysis of channel patterns over the last 200 years. The categories comprise mostly natural river types (confined, moderately confined single-channel, multi-channel, sinuous, meandering, incised meander) and those with a high degree of anthropogenic structural intervention (arched regulated, linear straightened, dammed-up). A great advantage of this approach is the relatively simple and time-efficient map survey that can be conducted for large areas in a comparative way.

Figure 4Decision tree for the classification of channel patterns in each grid cell. Numbering in the map segments refers to channel pattern categories as indicated by the coloured boxes above. The asterisk (*) indicates that no multi-channel river exists in the study area, and so this pattern is not recorded. The river-to-floodplain ratio (white arrow) gives the ratio between the length of the river course (m) and the length of the floodplain section (m). Data sources: Sächs. Ing.-Korps and Aster (1806) (old maps); GeoSN – Landesamt für Geobasisinformation Sachsen (2025) (recent maps).

The Sächsische Meilenblätter (Sächs. Ing.-Korps and Aster, 1806, 1816) and Von Deckersche Quadratmeilenblätter (von Decker and von Rau, 1822) are used here for mapping the historical river channel patterns, and the topographical map (1 : 25 000) of Saxony (GeoSN – Landesamt für Geobasisinformation Sachsen, 2025) is used for the mapping of recent structures. Each grid cell partially intersected by a river course is assigned a channel pattern category at a spatial resolution of 1 km2. If several possible channel patterns occur within a grid, the pattern that has the largest total share of a grid is used. Figure 4 shows the decision tree for the classification and mapping of channel patterns in each grid. As a criterion for distinguishing between confined and unconfined natural channel patterns with comparable sinuosities (types 1, 2, and 3 and types 4 and 5, respectively), we use the ratio of river width to the floodplain width, as illustrated by the bounding box in Fig. 4.

3.4 Floodplain land use

The form and intensity of land use in catchments and particularly in floodplains have been shown to significantly affect physico-chemical water qualities and, thereby, salmon habitat potential, including spawning and migration success (Rodger et al., 2024; Soulsby et al., 2024; Stefankiv et al., 2019). Land use can critically impact contaminant and nutrient influx (Krause et al., 2008; Lyubimova et al., 2016), oxygen levels, the temperature regime via shading effects (Fabris et al., 2017; Hrachowitz et al., 2010; Jackson et al., 2021), and the amount of detrimental suspended load within the river (Walling, 2005; Yu and Rhoads, 2018). According to waterbody structure mapping (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999), floodplain land use can be visually divided into seven categories (Fig. 5). Class 1 is not mapped in the assessment as such as this refers to a natural floodplain forest, which cannot be discerned clearly in the old maps. Class 2 encompasses floodplain woodland, and class 3 features floodplain grassland. Classes 4 to 7 encompass mixed land uses, with increasing amounts of built-up areas and agriculture. Mapped land-use amounts always refer to the geomorphological floodplain, featuring Holocene flood deposits according to BUEK 200 inside a given grid cell.

3.5 Barriers

Hydropower plants and their reservoirs are known to cause river fragmentation and impact natural flow regulation (He et al., 2024). Even when there is no reservoir present, weirs create slower-moving upstream river portions because they deepen the water, reduce flow velocity, and increase sediment deposition. Weirs also have downstream effects, creating low-suspension-loaded water that erodes at the lee side of the barrier (Mueller et al., 2011). The accumulation of multiple barriers across a river system drastically reduces the chances of migratory fish reaching their spawning grounds and, in consequence, increases the probability of their extirpation (Gowans et al., 2003; Lange et al., 2018).

For this study, we mapped structures with a potential barrier effect shown on the old maps. Due to the military and secret nature of the map material used, a high degree of reliability can be assumed with regard to the positioning of river barriers. For the current situation, we refer to the Saxonian Transversal Structures database (LfULG, 2024). It records 323 structures located in the Mulde River main tributary system. For the Vereinigte Mulde section located in Saxony–Anhalt, we consult the AMBER Barrier Atlas (AMBER Consortium, 2020), on the basis of which we document six more structures. Whereas the old maps feature only weirs and dams visible above the water surface, the recent databases also include features below. Vertical steps like ground sills with heights over 0.1 m were included, while ramps and ecologically rehabilitated weirs were excluded from the analysis. We presume that no artificial ground sills existed in the historical state.

In order to perform a semi-quantitative analysis of barriers in the Mulde River system, we create a measure of connectivity, the “cumulative barrier count”. The height and historical information on barrier operation were not part of our review. In this study, we considered the cumulative number of barriers as a proxy parameter for river connectivity. This represents the number of barriers which anadromous fish had to overcome in order to reach a specific grid cell in the Mulde River system. To account for cases where the river crosses the grid cell multiple times and/or where multiple barriers are present in the grid cell, the cumulative barrier count documents the maximum number of barriers.

3.6 Atlantic salmon catch data

A total of 1607 reports of Atlantic salmon in the period from 1432 to 2021 were recorded for the Elbe River system in order to document the historical salmon distribution (Hegemann et al., 2025) through 2021. The historical dataset includes 992 salmon reports of catches from secondary written sources with locations. This literature survey took as starting points the review studies of Wolter (2015) and Andreska and Hanel (2015). Additional references were added in the course of our study and are documented in Hegemann et al. (2025). Furthermore, recent distribution data from GBIF.org (2025) were included in the database. Here, 615 records from 1999 onwards were retrievable.

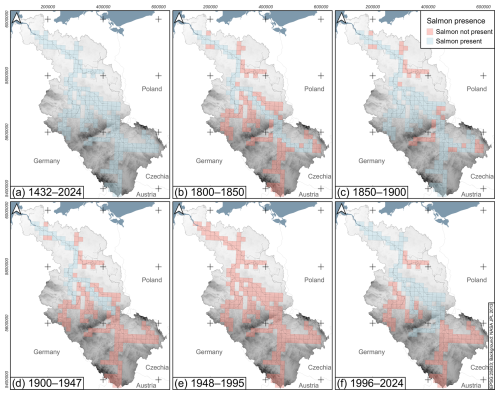

To delimit the distribution areas of salmon, salmon catch data were mapped in a simplified approach after Clavero and Hermoso (2015). Our model presumes that the recorded salmon catches also include a distribution of the migratory fish downstream of the fishing location. To this end, a binary dataset for each time slice relating to whether salmon were present or not is created in 16 km × 16 km grid cells (Henke et al., 2025). The approach makes it possible to work around the imprecise nature of historical sources by accessing the simple information of whether a salmon was sighted (Clavero and Hermoso, 2015). The catch data are not necessarily representative of the salmon population as natural and anthropogenic factors must be taken into account (Füllner et al., 2004b). The dataset models the distribution of salmon in the Elbe River system. The time slices are determined in 100-year spans for the period from 1500 to 1800 and in 50-year spans for 1800 to 2024 due to the higher availability of reports in the more recent periods.

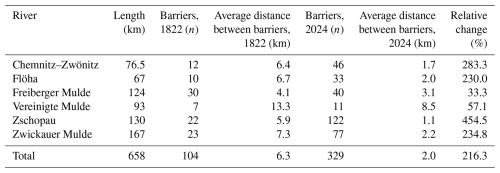

4.1 Channel patterns

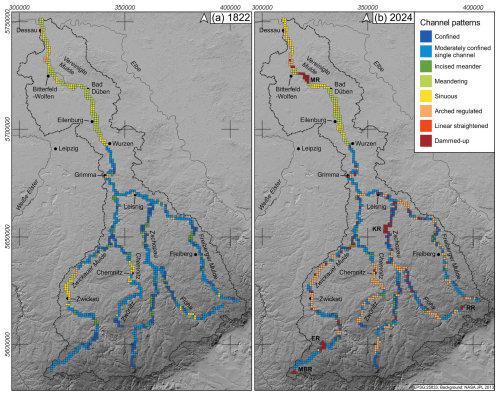

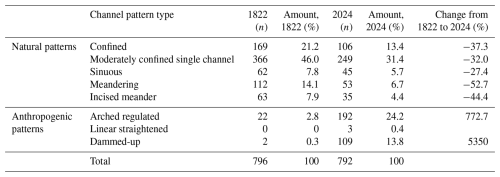

Channel patterns are mapped for 796 grid cells from the old maps (Fig. 6a) and for 792 grid cells from the recent topographic map (Fig. 6b). Our results show that channel patterns were clearly dominated by non-anthropogenic types (96.9 %) in 1822 (Table 1). The headwaters in the low mountainous areas are characterised by confined and moderately confined forms, whereas the Vereinigte Mulde River courses in the lowlands feature meandering and sinuous patterns.

Figure 6Comparative mapping (1822 vs. 2024) of channel patterns after Hohensinner et al. (2021) in the Mulde River system. Larger reservoirs are marked: Eibenstock Reservoir (ER), Kriebstein Reservoir (KR), Mulde Reservoir (MR), Muldenberg Reservoir (MBR), and Rauschenbach Reservoir (RR). Data source: see Table S1 in the Supplement.

Table 1Overview of the numbers of grid cells (n) with specific channel patterns in the Mulde River system for 1822 vs. 2024, after Hohensinner et al. (2021).

The data reveal a considerable decrease in grid cells containing natural river patterns in the study area between 1822 and 2024. Losses range from about one-quarter of total grid cells for sinuous river sections to about one-third for confined and moderately confined sections and approximately half for the incised meander and meandering sections. The largest total decrease in grid cells is documented for moderately confined sections. As expected, grid cells with anthropogenic river patterns increased between 1822 and 2024. Grid cells containing dammed-up sections increased by 5350 %, while grid cells with arched regulated sections increased by 772 % (Table 1). The relative number of grid cells with anthropogenic channel patterns rose from 3.1 % in 1822 to 38.4 % in 2024.

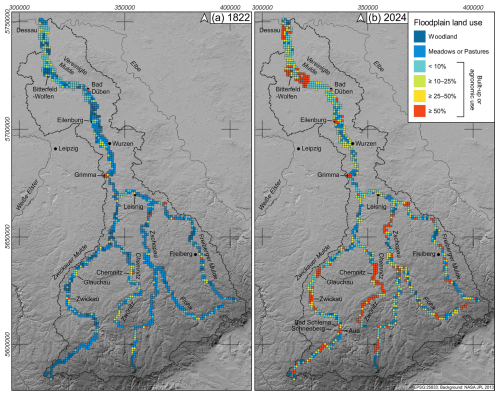

4.2 Floodplain land use

Floodplain land use is mapped for 979 grid cells (1 km2) from the old maps (Fig. 7a) and for 990 grid cells from the recent topographic map (Fig. 7b). In 1822, floodplain land use was predominantly characterised by woodlands and meadows or pastures (classes 2 and 3; 69.5 %). Together with extensively settled or agronomic areas (class 4; 21.2 %), these represent a large amount (90.7 %) of all grids. A small number of intensively settled grids are located in the urban areas of Grimma and Chemnitz and in a number of smaller cities along the tributaries.

Figure 7Comparative mapping of floodplain land use in the Mulde River system, 1822 vs. 2024. Data source: see Table S1.

Table 2Overview of the number of grid cells (n) with specific floodplain land-use classes in the Mulde River system for 1822 vs. 2024.

Between 1822 and 2024, land use in the Mulde floodplains intensified remarkably: the formerly dominating land-use classes 2 (woodland) and 3 (grassland) only make up one-quarter of mapped grids in 2024, indicating a loss of more than 60 %. Intensively used grids (classes 5 to 7) experienced the largest increase, from 9.3 % to 45.3 %. Out of these classes, grids with more than 50 % built-up area in the floodplain experienced the single largest increase of 1387 % (Table 2). Even in the upper reaches, the floodplains have been altered by anthropogenic mixed use.

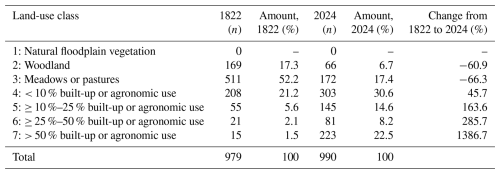

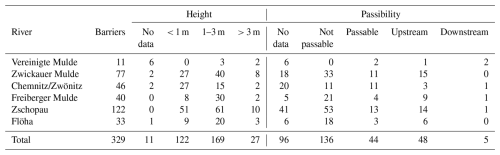

4.3 Barriers

For 1822, we identified 104 barriers in direct connection with the studied rivers (Table 3). The lowest number of barriers was found in the Vereinigte Mulde River, and the highest number was found in the Freiberger Mulde River. Averaged over river lengths, the Mulde River system contained a barrier every 6.3 km in 1822. The aforementioned rivers represent extremes: in the Vereinigte Mulde River, migratory fish would have had to pass a barrier every 13.3 km on average, while, in the Freiberger Mulde, distances between barriers were significantly shorter (4.1 km).

Table 3Mapped barriers in the Mulde River system for 1822 vs. 2024. The lengths of rivers are also given, with average distances between two barriers.

The Saxonian Transversal Structures Database (LfULG, 2024) and the AMBER Barrier Atlas (AMBER Consortium, 2020) currently document 329 barriers in the studied rivers. The Vereinigte Mulde River has 11 barriers, whereas the Zschopau River has 122, the largest number of barriers. Averaged over river lengths, a barrier is present every 2 km in the studied rivers, and, across all of them, the number of barriers has tripled. In the Zschopau River, the number of barriers has increased by 455 %.

Figure 8Comparative mapping of barriers in each grid cell (a, b) and cumulative barrier count (c, d) in the Mulde River system for 1822 and 2024. Panels (a) and (b) are based on the recent river courses. The cumulative counts (c, d) range from the Elbe estuary towards the headwaters. The mapped classes represent septiles in the 2024 data. The 256 km2 grid features the salmon presence for 1800 to 1899 and for 1996 to 2024. Data source: Henke et al. (2025); see Table S1.

Figure 8a and b show the barriers in each grid cell for the time slices of 1822 and 2024. In 1822, barriers in the Mulde system were distributed more evenly, with only three grid cells containing two barriers and no grid cell containing three or more barriers. Barriers were concentrated in the downstream and midstream sections of the Freiberger Mulde River and the upstream sections of the Zschopau River. Zwickauer Mulde shows a more even distribution, with a concentration around Zwickau. Notably, no barriers were present in the upstream sections of all tributaries in 1822. The increase in the number of barriers between 1822 and 2024 primarily happened in the upstream sections, with the highest concentrations in the Zschopau River and Zwickauer Mulde. Today, formerly completely barrier-free upstream sections in the Zwickauer Mulde, Zwönitz, Flöha, and Freiberger Mulde are largely dammed. Figure 8c and d show the cumulated barriers in grid cells. While the Elbe and Mulde up to Dessau were passable in 1822, a weir built in 1960 in Geesthacht, southeast of Hamburg, has moved the completely accessible area far downstream.

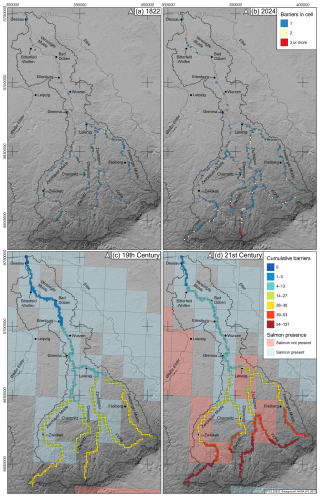

4.4 Historical data on Atlantic salmon distribution in the Elbe catchment

Figure 9a shows the total distribution area of the Atlantic salmon in the Elbe River system in all studied time periods. At the onset of the 19th century, the reported Atlantic salmon distribution only reached the Saale River and the upstream Elbe River reaches in the Bohemian Basin (Fig. 9b). No salmons are reported from the Mulde River in this time period. Between 1851 and 1900, the range of the salmon has the widest distribution of all time slices (Fig. 9c). It covers a large part of the Elbe River and its tributaries and extends to the headwaters of the Elbe, the Vltava, and the Otava rivers in the Czech Republic. In the Mulde River system, the range of the salmon includes the Zwickauer Mulde as far as Aue, the Chemnitz, the Zschopau, and a lower section of the Flöha (Fig. 8c). Salmon were also found in the Schwarze Elster and the Saale (Fig. 9c).

Figure 9Overview of modelled salmon habitat ranges. Comparative mapping of historical and recent Atlantic salmon reports in the Elbe River system. Data source: Henke et al. (2025).

From 1900 to 1949, the range of the Atlantic salmon is comparatively limited. It extends up the Elbe to the town of Ústí nad Labem and up the Saale to between the tributaries of the Weiße Elster and Unstrut rivers (Fig. 9d).

Between 1950 and 1995, the Atlantic salmon became extinct in the Elbe River system (Fig. 9e).

From 1996, an increase in the range of the Atlantic salmon can be seen again with the onsetting reintroduction programmes (Füllner et al., 2004b). The fishes migrated up the Ohře River as far as Karlovy Vary but, according to the available data, no further upstream in the Elbe (Fig. 9f). However, individuals were again recorded in the Mulde (Fig. 8d) and, for the first time, in smaller tributaries, e.g. the Stepenitz in the lower reaches of the Elbe.

5.1 Channel pattern: spatial variability, temporal changes, and eco-hydrological functioning

5.1.1 Lithological control of pre-industrial channel patterns

The results of the 1822 channel pattern mapping are considered to reflect a pre-industrial state, not yet exceedingly blurred in our categorisation by anthropogenic impacts. Hence, we resort to the data of this time slice in order to assess the lithological control on the formation of distinct channel patterns in the Mulde River system. It is a well-known phenomenon that lithological properties and the alignment of tectonic faults exert a strong influence on the formation of specific river types (Goudie, 2016; Montgomery, 2004; Twidale, 2004). In this regard, the Mulde catchment can be divided into (i) a bedrock-dominated southern part of the low mountain range and (ii) a smaller northern lowland part, downstream of the city of Wurzen, which is characterised by unconsolidated Neogene and Quaternary sediments (Figs. 2 and 6).

- i.

In the southern part, all rivers mainly flow concordantly with the major incline of the Ore Mountains fault block but, in some segments, also trend in parallel alignment with the Variscan strike (NE–SW) or with its cross-faults, i.e. perpendicularly to the latter (NW–SE). Courses along Variscan faults are, for example, inferred for the uppermost and lowermost reaches of the Zwickauer Mulde, the uppermost reaches of the Flöha, and the central segments of the Zwönitz and the Zschopau rivers. In contrast, cross-fault-induced courses can be interpreted for the central parts of the Freiberger Mulde, the middle to lower reaches of the Flöha, the lowermost reaches of the Chemnitz River, and the uppermost stretches of the Vereinigte Mulde River (Fig. 2). In several instances, this tectonic pattern leads to large-scale rectangular course changes, supposedly at the junction of faults, as evident for the Flöha, the Zwönitz, and the Vereinigte Mulde around the city of Grimma. Such fault-line valleys are usually relatively narrow and fairly straight (Twidale, 2004). Even though this general tendency holds true for the bulk of our channel pattern data, we propose that valley metrics and, especially, the respective river types are at least just as controlled by lithologies. The hard, erosion-resistant magmatic and metamorphic rocks predominant in the southern part of the catchment favour the formation of small-width valleys hosting rivers with confined or moderately confined channel patterns (Goudie, 2016; Schanz and Montgomery, 2016; Wagenbreth and Steiner, 1990). Hence, these two categories cover most of the southern part of the Mulde River system (Fig. 6). These two types are not easily distinguished lithologically based on a geological map. An exception is the Eibenstock Granite Pluton (EGP), about which one can say tentatively that it allows for slightly wider valleys (moderately confined) as opposed to the more confined channel patterns that form outside of the pluton (Figs. 2 and 6). Incised meanders that occur over short stretches in all rivers are likely inherited from the time before the Neogene uplift of the fault block (Dente et al., 2021; Wagenbreth and Steiner, 1990). Conversely, the presence of wider valleys accommodating rivers with a sinuous channel pattern is inextricably linked with the distribution of softer, more friable sedimentary rocks from the Upper Carboniferous to the Permian period. These lithologies, being less resistant to lateral fluvial planation, are mainly found throughout the Molasse Basin (affecting the Zwickauer Mulde and the Chemnitz rivers) and the two small fault-related Olbernhau (OB) and Brandov basins (BB) along the Flöha River (Figs. 2 and 6). North of Zwickau, a stretch of arched regulated channel exists, even in the early 19th century. According to the valley and floodplain morphologies, however, this segment would originally qualify as sinuous as well if anthropogenic bank enforcements and course changes were disregarded. Therefore, the allocation of the sinuous channel pattern is nearly congruent with the extent of the aforementioned basin structures. Apart from planform geometry, lithological differences can also affect the longitudinal profile, i.e. the gradient of a river. Figure 10 shows the composite profile of current gradients of the major rivers in the Mulde River system. While the smaller inflections are almost entirely caused by artificial impoundments and their respective backwaters, large-scale slope changes refer to natural knickpoints (e.g. over total river lengths of 210 and 190 km in the Freiberger Mulde and Chemnitz rivers, respectively). Because the degree and manner of bedrock control of the formation and propagation of knickpoints are a longstanding matter of debate (Goudie, 2016; Schanz and Montgomery, 2016), here, an explanation of the knickpoints would require detailed on-site investigations, which is why we refrain from a geological interpretation of them.

- ii.

For the northern part of the catchment, the Mulde River moves from the uplands dominated by bedrock into the lowlands, where thick and highly erodible Cenozoic loose sediments determine the fluvial architectures. The river mainly follows the low gradient towards its base level, which is the confluence with the Elbe River. The course is gently guided by the several-kilometres-wide valley of the Upper Pleistocene (Weichselian) Lower Terrace, the deposits of which are constantly reworked and overlain by up to 3 m of Holocene overbank fines (Vetter, 2011b). Fault-induced course adjustments are not discernible in this part. Accordingly, the meandering channel pattern is by far the most frequent category under pre-industrial conditions (Fig. 6). Shorter sinuous stretches occur subordinately but are occasionally the product of recent neck cut-offs temporarily lowering the sinuosity below 1.5 so that the meandering pattern cannot be assigned. In other instances, a slight unilateral confinement exists, specifically when the Mulde River is positioned at the edge of the Weichselian Valley and creates a cutbank into more resistant glacial and sometimes Neogene deposits. This is the case just downstream of Bad Düben, where the river is forced to bypass a ridge of the Saalian terminal moraine (Eissmann, 2002a), and at Gruna, north of Eilenburg, where the Mulde River erodes into Saalian and Elsterian deposits on its left bank, even exposing small Neogene lignite seams at low water levels.

5.1.2 The Industrial Revolution: temporal changes in channel patterns

In 1822, the upper Mulde River courses were dominated by confined and moderately confined single-channel pattern types (Fig. 6a). In the lower reaches of the Vereinigte Mulde River, sinuous and meandering channel patterns were common. The mapped channel patterns reveal arched regulated segments around Zwickau and Chemnitz, where they coincided with the wider valleys of the Molasse Basin (Figs. 2, 6). Arched regulated stretches also occurred in the lower course of the Freiberger Mulde River and in Grimma. All of these instances can be related to urban centres with important textile production (Kiesewetter, 2007; Mieck, 2012), the dependence of which on hydropower necessitated a certain degree of river regulation.

Proto-industrial structures in conjunction with (Hahn, 2005; Kiesewetter, 2007) coal resources – mainly in the Molasse Basin but also in the smaller Olbernhau and Brandov Basins (Fig. 2) – led to a rapid development and to Saxony's becoming a pioneer region for central European (Hardach, 1991) industrialisation. Leading sectors were (i) the textile industry, mostly in locations of previous textile production and many additional ones (e.g. Frankenberg at the Zschopau river), (ii) engine construction (especially in Zwickau, Chemnitz, and the city of Zschopau), and (iii) the paper industry (Friedreich, 2020; Mieck, 2012). The last was established in several industrial villages throughout the region (e.g. Grünhainichen at the Flöha river), often in narrow valleys with access to hydro-energy and timber. Inseparably linked to this evolution was rapid population growth and the expansion of further infrastructure. This involved the construction of (i) roads and railway tracks along narrow valleys from the middle 19th century (Friedreich, 2020; Kiesewetter, 2007), for which bank enforcement was needed; (ii) dams equipped with turbines for electricity generation from the late 19th century; and, ultimately, (iii) large water reservoirs for drinking-water supply and discharge (Theuerkauf and Kaiser, 2024) regulations. Those reservoirs were mainly built in the 1920s (Kriebstein and Muldenberg) and the second half of the 20th century (Eibenstock and Rauschenbach) (see Fig. 6).

Therefore, by 2024 anthropogenic channel patterns had increased significantly. The dammed-up category appears in former confined and incised meander channel patterns (Fig. 6b), which is primarily due to the construction of dams with associated hydropower plants. Several freshwater reservoirs have also been built on the Mulde River tributaries (Fig. 6b). Arched regulated channel patterns are recorded primarily in urban areas such as around Chemnitz or Freiberg (Fig. 6b). The increase in flood protection measures can also be observed much more frequently on the recent topographic map and leads to a classification of the lower course of the Vereinigte Mulde River as arched regulated channel patterns.

5.1.3 Eco-morphological functioning of channel patterns: suitability of the riverbed as a habitat for migratory fishes

By analysing the channel pattern types, integral statements can be made about the suitability of a riverbed as a habitat for migratory fishes. The roughness of the riverbed, the shear forces, and the flow conditions (turbulent or laminar) are factors that determine the formation of mesohabitats in watercourses. Meandering and sinuous channel patterns are prominent in the lower reaches of the Mulde River system and reveal a high width variance that speaks to the frequency of width changes in the bank–full riverbed (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999). Water width and water depth are closely related. Wide river courses are shallow, and narrow river courses are deep. Therefore, the width of a channel is also directly related to flow velocities, and, in turn, it affects the grain size composition of the riverbed (Vetter, 2011a, b) and the longitudinal variability of mesohabitats (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999), which are important requirements for the different life stages of salmon (Füllner et al., 2004a). Incised meander and confined channel patterns are associated with low latitudinal width variance and might reduce salmon habitat suitability (Füllner et al., 2004a).

Channel patterns reflect specific flow conditions and sediment supply, which influence the natural presence of channel bars in the riverbed. Typical form elements are point bars, attached bars, concave bars, mid-channel bars, and multiple bars (Hooke and Yorke, 2011; LANUV, 2023). Most of these are longitudinal bars that are formed by grain-selective sedimentation and compose a finer substrate compared to the adjacent bed substrate (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999). Channel bars are particularly relevant for salmonids. The ecological importance of channel bars lies in the fact that their presence indicates a structurally rich and dynamically balanced riverbed (MUNLV, 2022). Channel bars provide habitat diversity and serve as important spawning and nursery habitats for fish. In addition, they create large velocity gradients due to friction effects and thus promote the formation of calm zones during flood events (Pan et al., 2022), which is particularly important for the survival of juvenile fish. Nevertheless, the presence of channel bars is not necessarily to be expected in every section of the pre-industrial river course (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999). For instance, in straight reaches of meandering rivers, they are known to be extremely rare – that is, if they occur at all (Hooke and Yorke, 2011).

Due to the high variability of ecological niches in natural channel pattern types, organisms with very different habitat requirements can live in close proximity to each other (Newson and Newson, 2000). Anthropogenic changes in the channel pattern type have an influence on shear forces, flow conditions, and the ratio of erosion to deposition, resulting in a direct impact on aquatic mesohabitats (Newson and Newson, 2000).

Human interventions such as straightening, damming, or the construction of power plants can have a particularly strong effect on the distribution of salmon (MUNLV, 2006). Therefore, it is particularly interesting to document changes from near-natural to anthropogenic channel pattern types.

Width variance, an important factor for the ecological connectivity of rivers (LANUV, 2011), is higher in near-natural channel patterns and occurs at shorter intervals than in anthropogenically influenced areas. As of 2024, urban river sections showed very poor width variance due to arched regulated and linear straightened channel patterns.

5.1.4 Validity and applicability of the channel pattern parameter in the Mulde River system

The mapping of river channel pattern types from recent topographical maps is possible in the same mode as the classification from the old map sheets, indicating the high applicability of the approach of Hohensinner et al. (2021). The applied grid approach can generally be considered to be a suitable method as it allows large datasets to be divided into manageable sections, thus facilitating data processing. With this method, channel patterns can be classified and quantitatively assessed over long distances, allowing for comprehensive analysis between different river systems. Furthermore, mapped pre-industrial channel patterns can be distinguished with regard to lithology and the closely related topographical conditions. This indicates the high validity of the approach employed.

5.2 Floodplain land use – spatial variability, temporal changes, and ecohydrological functioning

5.2.1 Controlling factors on floodplain land use

For the interpretation and contextualisation of changes in floodplain land use over the past 200 years, the subdivision of the Mulde catchment into a southern and a northern part can be considered. This seems appropriate because of a remarkable coincidence between natural factors and territorial affiliation from the 19th century onwards, both obviously affecting the intensity and form of floodplain land use. While the southern, bedrock-dominated part has been under Saxonian governance for hundreds of years, most of the northern, gravel-bed-dominated part was ceded from Saxony to Prussia in 1815, with the border situated between Wurzen and Eilenburg (Fig. 2). Only the lowest Mulde River reaches around the confluence with the Elbe River belonged to the state of Anhalt. Due to this spatial coincidence, the two parts of the catchment have seen largely coherent internal developments with their respective co-evolutions.

- i.

For the southern part of the Mulde River system, floodplain land use clearly reflects the pre-industrial stage of urbanisation and economic development in 1822. According to our classification system, the intensity of floodplain use was low (Fig. 7). However, the river sections around the textile industry centres mentioned above and Waldheim show intensive floodplain land use at this point. In particular, upstream of Freiberg and in the upper courses of the Zwönitz and Zschopau rivers, increased floodplain land use can be attributed to ore mining. Mining had a strong influence on the entire region from the 12th century until its gradual decline in the 18th and 19th centuries (Greif, 2015; Theuerkauf and Kaiser, 2024).

- ii.

Regarding floodplain land use in the northern part of the Mulde River downstream of Wurzen, proto-industrial structures were less well established in 1822 (Mieck, 2012), with three notable exceptions: (1) near Eilenburg, in the 17th century, a millrace was branched off from the Mulde River and was canaled through the city, promoting mechanised textile production (Felgel et al., 1993); (2) in Bad Düben, lucrative mining of Neogene deposits for alum production used for dyeing and tanning went on from the 16th to 19th century directly at the Mulde River (Lampadius, 1801) (this wood-demanding process also released sulfuric effluents into the stream, and a huge spoil tip still forms a cutbank of the Mulde near the city); and (3) Dessau's being the major city in the Duchy of Anhalt and one of the centres of German enlightenment satisfied the infrastructural and socioeconomic prerequisites for further development, with high investments in educational institutions (Brockmeier, 2010). Outside of these nuclei, the region had a pronounced rural character, which is plainly evidenced in low intensities of floodplain land use (Fig. 7).

The Vereinigte Mulde River is infamous for its short but fierce flood surges (Puhlmann, 1997) and exceedingly strong lateral migration dynamics, attested to by the multitude of natural meander cut-offs and oxbow lakes. These natural preconditions may have complicated the construction and maintenance of commercial sites along the river.

5.2.2 A strong increase in floodplain land use during the last 2 centuries

In the southern part of the Mulde River system, anthropogenic classes in floodplain land use have increased by several hundred percent around the mentioned industrial centres and cities in the infrastructurally developed narrow valleys (Fig. 7; Table 2). By comparison, relatively few changes have been recorded for the lowermost reaches of the Zwickauer and Freiberger Mulde rivers and for the upper sections of the Vereinigte Mulde River. Beyond these industrialisation processes, anthropogenic floodplain land-use classes attest to one of the world's largest uranium mining operations in the regions of Aue, Schneeberg, and Bad Schlema (Fig. 7b). This was carried out by the Soviet state-owned enterprise “Wismut” in the 20th century (Albrecht et al., 2022; Paul, 1991).

In the northern part of the Mulde River system, the effects of industrial propagation over the last 2 centuries (Mieck, 2012; Schönfelder et al., 2009) can be seen in current floodplain land use, which clearly captures the centres of development in Dessau, Bitterfeld-Wolfen, and Eilenburg (Fig. 7b). Beyond these, the overall activity increased due to villages extending into the floodplain and due to a higher share of agricultural use at the expense of strongly diminished woodlands.

5.2.3 Eco-morphological functioning of floodplain land use: a parameter of human impact and pollution

Within waterbody structure mapping, floodplain land use is identified as a parameter of anthropogenic impacts on the natural fluvioscape (Zumbroich and Müller, 1999) and may influence migratory fish stocks. Low water temperatures, high water quality, and high oxygen saturation are essential for salmon spawning waters. Decreases in riparian forests, agrarian fields, craft, or urban areas each result in river pollution, water warming, and fluctuating water quality (Füllner et al., 2004a; Waterstraat and Wachlin, 2012). Furthermore, floodplain drainage and surface runoff within urban areas and on farmland lead to increased suspension load and silt–clay sediment input into rivers (Füllner et al., 2004b). Organic-rich fine sediments are often washed in, which reduces the oxygen content of rivers (Waterstraat and Wachlin, 2012).

Throughout the entire Mulde catchment, the industrial development set in motion in the 19th century continued in the Mulde River system until the late 20th century. During that time, industrial companies were held to low standards with regard to effluent treatment (Naujoks and Fischer, 1991; Petschow et al., 1990), such that, in the late 1980s, the Mulde River was considered to be one of the most severely polluted rivers in Europe, with adverse hydrogeochemical repercussions even in remote regions such as Hamburg and the Wadden Sea (Böhme et al., 2005). After the demise of the German Democratic Republic in 1990, the water quality of the river rapidly and significantly improved within just a few years (Otto and Mleinek, 1997). However, to this day, large-scale uranium (and historical) mining heaps are still situated near or within the floodplain (Theuerkauf and Kaiser, 2024), and the industrial and mining legacy is still archived in the overbank deposits, leading to legal restrictions on agricultural use in some areas (Bräuer and Herzog, 1997). During flood events, these deposits get reactivated, which results in abrupt temporary deteriorations of the river's chemical quality (Klemm et al., 2005; Knittel et al., 2005; Wilken et al., 1994).

5.2.4 Validity and applicability of the floodplain land-use parameter in the Mulde River system

Using the grid approach, the semi-quantitative parameter of floodplain land use provides a comparative overview of the Mulde River system at multi-temporal scales. The mapping approach is applicable for old maps and modern topographical maps without any restrictions. However, the simple classification system does not allow for distinctions as to whether the built-up areas are characterised as industrial, urban, or otherwise. This means that conclusions about the degree of river pollution are strictly limited. However, the parameter offers the possibility of carrying out large-scale assessments and using it to delineate areas that can then be analysed for potential sources of pollution in more intensive studies.

5.3 Barriers – spatial variability, temporal changes, and ecohydrological functioning

5.3.1 Controlling factors on barrier occurrences in the Mulde River system

Barriers have been built on watercourses for a long time and have served a variety of purposes. The medieval period saw a significant increase in the construction of barriers, which is thought to be closely linked to the widespread employment of hydropower in the form of water mills (Lenders et al., 2016).

Regarding the number and distribution of barriers in the Mulde River system in 1822 (Fig. 8a), the lasting effects of ore mining can be interpreted. Out of 104 barriers, the highest numbers and densities appear to be linked to mining hotspots, e.g. the Freiberger Mulde and the Zschopau rivers (Table 3). Historical mining activity is known to have had a high demand for hydropower, e.g. to operate pumping stations (for the expulsion of gallery waters) and hammer mills, and it also requires large amounts of timber, with barriers being used for the the rafting of which as well (Cembrzyński, 2019). However, the former textile production relied equally on hydropower, and several other crucial reasons for constructing barriers existed, such as water mills (for grain and timber) and fish weirs. Hence, a definite assignment of any barrier to a specific purpose is challenging within the scope of our investigations.

Regarding the Vereinigte Mulde River in the northern part of the Mulde River system, the structurally weak region is also evidenced by the low number of barriers, of which only seven existed in 1822 (Fig. 8a). This includes the Eilenburg weir, which diverts the aforementioned millrace, and a mill and fish weir in Dessau, which is documented from as early as the 13th century (Reichhoff and Refior, 1997).

5.3.2 A large increase in barrier installations over the last 2 centuries

From 1822 to 2024, the number of barriers in the Mulde River system increased from 104 to 329 (Table 3, Fig. 10), with the largest today being 57 m high (Eibenstock Reservoir, Fig. 6b). This development can also be observed in the cumulative numbers of barriers (Fig. 8b). River sections with no or little obstruction have moved downstream, while barriers that must be passed to reach mountainous upstream sections have multiplied by up to 3. For example, 137 barriers must be passed to reach the source of the Zschopau River.

The rise in the 19th and 20th centuries in the numbers and density of barriers is not equally distributed across the Mulde River system. Regarding the mountainous southern part, the most affected are (in order) the Zschopau, Chemnitz/Zwönitz, and Flöha rivers, in which the average distance between two barriers dropped from around 6 to < 2 km (Table 3), and, for many sections, it can even be below 1 km (Fig. 10). A big proportion of the new barriers serve the purpose of electricity generation. The fact that, in the southern Mulde River system, the Freiberger Mulde, which showed the highest barrier density in proto-industrial times, now features the lowest one arguably highlights an apparent spatial shift of economic development away from the mining town of Freiberg despite the presence of a globally renowned university for mining and engineering (Munke, 2020).

From 1822, the northern part of the Mulde River system only gained a few additional barriers but with one being the Muldestausee reservoir, which is significant (Figs. 6b and 10). For more than 2 decades after its construction in 1976, it completely interrupted the ecological connectivity of the Mulde River (Geisler, 1998) until a fish migration aid was installed in the early 2000s. More recently, the reservoir and the downstream weirs in Raguhn and Jessnitz were given a secondary purpose as hydroelectric power stations.

5.3.3 The eco-morphological functioning of barriers: the parameter of connectivity

The construction of barriers such as fish weirs, mill weirs, and dams with reservoirs results in a modification of the natural fluvial–geomorphological structure, of the sediment balance, and of the eco-hydrological connectivity (Downward and Skinner, 2005; Fehér et al., 2014; He et al., 2024; Meybeck and Vörösmarty, 2005). As a result, the ecological consequences of barriers are manifold. The access to spawning sites for anadromous fishes like salmon may be obstructed (Chen et al., 2023). However, non-migrating fishes and invertebrate species can also be affected as most of these are unable to traverse even small dams, resulting in the disruption of natural habitats. The installation of fish migration aids can help with maintaining the longitudinal continuity between fish habitats. Nevertheless, traversing fish passes results in delays, energy loss, and higher mortality (Rivinoja et al., 2001). Over the course of longer fish migrations, even minor effects may add up across river networks to pose greater threats to affected species (Loures and Pompeu, 2019). Furthermore, the construction of barriers alters the natural sediment transport, with riverbed aggradation upstream of the dam and river incision downstream (Graf, 2006; Morris and Fan, 2010).

Regarding the Mulde River system in general, it will take time to reset the structural interferences in the river that were inherited from the era of industrialisation. Although efforts have been made in the last 3 decades to improve ecological potential and connectivity, e.g. by equipping a big share of the barriers with fish ladders, the sheer number and density of these barriers, especially in the upper catchment, remain problematic.

5.3.4 Validity and applicability of the barrier parameter in the Mulde River system

More detailed information about potential passibility is available for many of the current barriers in the Mulde River system and is presented in Table 4.

Table 4Height and passibility data for 2024 barriers. All data columns represent counts (n). Passibility is given following LfULG (2024). Data source: AMBER Consortium (2020) and LfULG (2024).

This information cannot be easily transferred to earlier times as any renovation work or weir heightening is not documented. Therefore, our diachronic comparative approach is limited exclusively to the determination of the presence or absence of barriers.

A comparison between the dammed-up channel patterns and the barriers is possible if one starts from the dammed-up channel pattern (Fig. 10). Conversely, however, it is not possible to conclude from the barriers that there is a dammed-up channel pattern because the backflow effect is usually not transferable to the grid cell, especially with the smaller barriers.

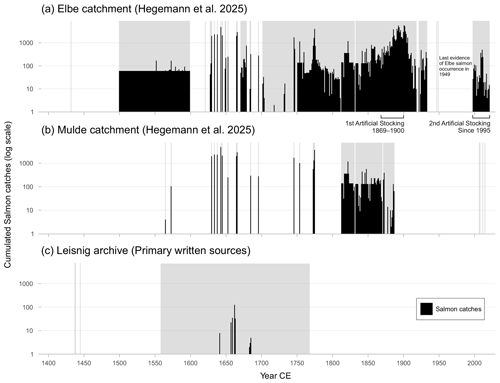

5.4 Potential and limitations of the historical dataset on Atlantic salmon distribution in the Elbe catchment

The dataset on the salmon catches enables a spatial and temporal reconstruction of salmon reports in the Elbe River system (Fig. 9) and represents an extension of an earlier dataset compiled by Wolter (2015). For the first time, the dataset is provided as an open-access dataset (Hegemann et al, 2025). The salmon catch record is based on secondary documented historical sources, with simplified information on cumulative catches per year (Fig. 11a, b). Whereas the data since 1850 might reflect a reliable base due to more systematic documentation of numerous fisheries, including in the context of or as part of artificial spawning programmes, the data from the early modern period and the Middle Ages are patchier.

Figure 11Histogram of documented salmon catches in (a) the Elbe catchment, (b) the Mulde catchment, and (c) the Leisnig archive from 1432 to 2024. Data for the time interval before 1850 in panels (a) and (b) are based only on secondary written sources. Data from panel (c) are not included in panels (a) and (b). Grey bars indicate time intervals with salmon reports but without concrete catch numbers. Elbe catches between 1500 and 1600 are based on an average information in the written source. Data sources: (a, b) Hegemann et al., 2025; (c) Kunze, 2007; HStA Dresden 10036 Finanzarchiv, Loc. 37651, Rep. 42, Sect. 1, Leisnig, No. 0003; HStA Dresden 10036 Finanzarchiv, Loc. 33858, Rep. 27, Leisnig, No. 0007.

In order to further evaluate the data quality, we conduct an initial micro-historical quality check by surveying previously un-analysed primary written sources in the Saxonian Hauptstaatsarchiv (Fig. 11c) and comparing the results with the previous dataset based on secondary sources only (Fig. 11a and b). The subject of the quality check is the electoral family salmon weir (Lachsfang) in the Freiberger Mulde River near Leisnig (Fig. 11c). This was built in 1617-1618 on the orders of Sophie of Brandenburg (1568–1622). The Amt Leisnig had been granted to her in 1602 as part of her dower (Essegern, 2007), and the salmon catch was mainly used to supply her kitchen (SächsHStA, n.d.). The salmon catch was located at the weir of the Leisnig upper mill (Obermühle), which was first mentioned in 1378 and leased to the town council in 1548 (Kunze, 2007). The electoral family maintained the salmon catch until the second half of the 18th century. From then on it was considered to be increasingly unprofitable due to frequent damage and constantly rising repair costs and was finally abandoned.

The comparison of the three histograms (Fig. 11a–c) clearly shows that a systematic survey of primary written sources will greatly enhance the historical knowledge on early modern salmon catches with regard to the total numbers but also with regard to the somewhat simpler issue of salmon presence or absence during a specific time interval and space. Therefore, early modern data from secondary written sources alone are not suitable for a robust quantitative historical analysis but can serve as a starting point.

5.5 Outlook: potential and limits of the waterbody data and the preliminary historical data on Atlantic salmon distribution in the Mulde River system

Our data on historical waterbody structure allow for a spatial and temporal assessment of the variability and changes in channel patterns, floodplain land use, and cumulative barriers for the Mulde River system. Using our semi-quantitative grid approach, the data on the waterbody structure from 1822 and 2024 can be compared with the data on historical salmon catches on a centennial scale. For the salmon catches, we used the complete dataset from 1801 to 1900 as this is much more reliable especially for the second half of the 19th century than the probably very incomplete dataset from the first half of the 19th century alone.

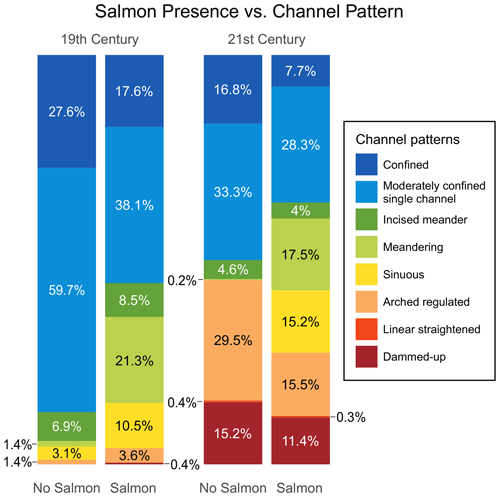

A comparison between channel patterns and salmon presence indicates a higher portion of meandering and sinuous channel patterns in grid cells with salmon presence for both time intervals (Fig. 12). In the 2024 time slice, grid cells without salmon presence display a higher portion of anthropogenic channel patterns.

Figure 12Stacked bar plots of channel patterns after Hohensinner et al. (2021) for grid cells with and without salmon presence in the Mulde River system for the 19th and 21st centuries. Data source: see Table S1.

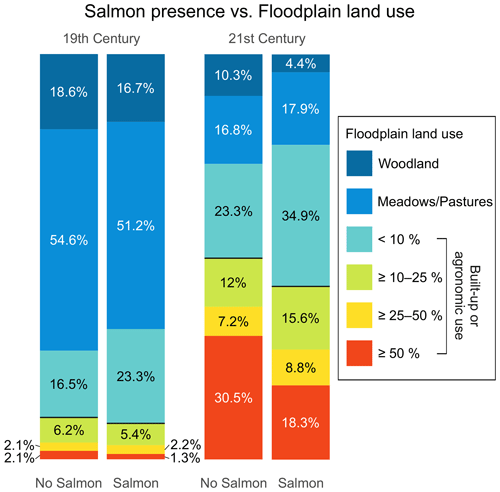

A further comparison is promising for floodplain land use as a potential pollution proxy and for salmon presence in the Mulde River system. Grid cells with salmon presence show lower floodplain land-use intensities (classes 2–4) for both time slices (Fig. 13). This effect is even more pronounced for the 2024 dataset.

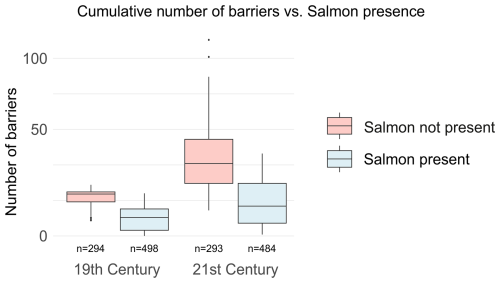

Figure 13Stacked bar plots of floodplain land use for grid cells with and without salmon presence in the Mulde River system for the 19th and 21st centuries. Data source: see Table S1.

The combination of both the historical salmon catches and the cumulative barrier data shows a decline in salmon presence with an increasing number of barriers for both time intervals (Fig. 8). There has also been a decline in salmon presence in the upper reaches of the Mulde River in the 21st century (Fig. 8b), which may be associated with the significant increase in barriers over the last 200 years. The same has been true for the entire Mulde River system (Fig. 14). Accordingly, the evidence for salmon presence decreases noticeably as the number of barriers increases.

Figure 14Boxplot of cumulative number of barriers and salmon habitat ranges for the entire Mulde River system. N is the number of grid cells with or without evidence for salmon for the respective time slices. Data source: see Table S1.

The comparative analysis of historical waterbody structures and historical salmon reports must be interpreted with care. Our datasets only form an initial stage here. Nevertheless, the approach is promising because larger spatial comparisons – and, therefore, integration of additional river systems – will enlarge the spatial heterogeneity of waterbody structures. In addition, the semi-quantitative grid approach can be improved by the consideration of additional time intervals (Zielhofer et al., 2025) and by the consideration of primary historical sources, especially for the medieval and early modern periods.

In this study, three parameters are developed and applied, comparatively documenting changes in the waterbody structure in the Mulde River system between 1822 and 2024. The parameters are based on the analysis of old maps and the most recent topographical map. All three parameters, namely channel pattern, floodplain land use, and barriers, showed very good applicability with regard to the two analysed map series. They allow, for the first time, a comparative assessment of the waterbody structure from a historical perspective for the Mulde River system.

The natural channel patterns show a spatial differentiation in terms of upper and lower reaches on the one hand and the bedrock on the other. The anthropogenic impact in the Mulde River system is made evident by the noticeable increase in anthropogenic channel patterns (dammed-up, arched regulated, and linear straightened).