the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Spatiotemporal dynamics of river channel patterns during the last 400 years south of Leipzig, Germany

Johannes Schmidt

Sophie Lindemann

Felicitas Geißler

Michael Hein

Niels Lohse

Julia Schmidt-Funke

Matthias Hardt

Schmidt, J., Lindemann, S., Geißler, F., Hein, M., Lohse, N., Schmidt-Funke, J., and Hardt, M.: Spatiotemporal dynamics of river channel patterns during the last 400 years south of Leipzig, Germany, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 74, 355–381, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-74-355-2025, 2025.

The Elster–Pleiße floodplain south of Leipzig has undergone significant hydromorphological changes over the past few centuries, influenced by both natural processes and anthropogenic interventions (e.g. characterized by the repurposing of former river courses into mill races and other engineered water-management channels). This study employs selected mapping of fluvial–geomorphological features based on a Light Detection and Ranging Digital Terrain Model (LiDAR DTM; 1×1 m resolution) and the analysis of old maps to reconstruct past river dynamics and identify changes in channel morphology. Geomorphological features, such as oxbows, ridge-and-swale point bar structures, crevasse splays, and levees, reveal an earlier, more dynamic floodplain characterized by meandering and anabranching channels, which transitioned into a system of stabilized, largely immobile watercourses. Comparative analyses of old maps spanning the 16th to 20th centuries indicate a gradual reduction in river sinuosity and lateral migration, coinciding with increasing human modifications such as mill races, timber rafting canals, and flood protection measures. The major transformations date back to at least the late 16th century and may be even earlier in origin. Key drivers include the straightening of channels, floodplain aggradation, and the impact of open-cast lignite mining in recent centuries. The study highlights the complex interplay of sedimentary processes and anthropogenic activities in shaping the floodplain's evolution. This combined approach allows a detailed examination of the relative chronology of changes and helps identify topographic legacies left by dynamic floodplain systems, enhancing our understanding of the evolution of these landscapes. Understanding these long-term dynamics provides crucial insights for contemporary river restoration and flood management strategies.

Die Elster-Pleiße-Aue südlich von Leipzig hat im Verlauf der vergangenen Jahrhunderte erhebliche hydromorphologische Veränderungen erfahren, die sowohl durch natürliche Prozesse als auch durch anthropogene Eingriffe geprägt wurden (z.B. durch die Umwidmung ehemaliger Flussläufe zu Mühlgräben und anderen wasserbaulichen Kanälen). In dieser Studie werden ausgewählte fluvial-geomorphologische Formen anhand eines LiDAR-DTMs (Light Detection and Ranging Digital Terrain Model; 1×1 m Auflösung) sowie historischer Karten ausgewertet, um frühere Flussdynamiken zu rekonstruieren und Veränderungen in der Gewässermorphologie zu identifizieren. Geomorphologische Merkmale wie Altarme, Gleithang-Strukturen, natürliche Uferdämme und -durchbrüche (crevasse splays) weisen auf eine ehemals deutlich dynamischere Auenlandschaft mit mäandrierenden und verflochtenen (anabranching) Flussläufen hin, die sich in ein System weitgehend stabilisierter, immobil gewordener Gewässer transformiert hat. Der Vergleich historischer Karten vom 16. bis ins 20. Jahrhundert zeigt eine allmähliche Abnahme der Sinuosität und der lateralen Dynamik, die mit zunehmenden menschlichen Eingriffen – wie dem Bau von Mühlgräben, Flößereikanälen und Hochwasserschutzmaßnahmen – einhergeht. Die maßgeblichen Umgestaltungen lassen sich mindestens bis in das späte 16. Jahrhundert zurückverfolgen und könnten sogar noch älter sein. Zu den zentralen Einflussfaktoren zählen Flussbegradigungen, Sedimentationsprozesse in der Aue sowie in jüngerer Zeit der Einfluss des Braunkohletagebaus. Die Studie unterstreicht das komplexe Zusammenspiel zwischen sedimentären Prozessen und anthropogener Überprägung bei der Ausformung der Auenlandschaft. Der kombinierte Ansatz ermöglicht eine detaillierte Betrachtung der relativen Chronologie dieser Veränderungen und hilft, topographische Relikte dynamischer Auenprozesse zu identifizieren. Dadurch wird das Verständnis der Landschaftsentwicklung vertieft. Das Wissen um diese Langzeitdynamiken liefert zugleich wichtige Erkenntnisse für die heutige Flussrenaturierung und das Hochwassermanagement.

- Article

(15293 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(353 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Floodplains and riverine areas are crucial to ecological sustainability in Europe (European Parliament and Council of the European Union, 2000; Schindler et al., 2016). However, the anthropogenic restructuring of rivers and floodplain landscapes in Central Europe is evident, and its effect is increasingly problematic (Tockner et al., 2010, 2022; Stammel et al., 2021). Pristine riverine systems are now rare. In Germany, the floodplain status report highlights the urgent need for revitalization (Koenzen et al., 2021). In accordance with the guidelines for the revitalization of floodplains, reference models are indispensable. To evaluate potentially natural conditions, the historical development of the river should be examined (Koenzen, 2005; Maaß et al., 2021). In addition to their natural characteristics and functions, floodplains and riverine areas are closely related to the history of the cultural landscape of Central Europe (Brown et al., 2018; Hein, 2020), and the remnants of these areas are considered valuable for protection (Council of the European Union, 1992).

Knowledge about historical river changes provides critical information for contemporary river management and restoration efforts (Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina e.V., 2024). By understanding past river dynamics, sedimentation patterns, and floodplain evolution, the development of strategies can improve ecological resilience (Hein et al., 2016; Brown et al., 2018; Maaß et al., 2018). These historical perspectives are essential for the implementation of adaptive management practices in the face of climate change and anthropogenic pressures (Heyden and Natho, 2022; Serra-Llobet et al., 2022). Typically, changes in river pattern and fluvial dynamics are often influenced by hydroclimatic factors (Notebaert and Verstraeten, 2010; Macklin and Lewin, 2019). Variations in precipitation levels and changes in vegetation cover can lead to alterations in river discharge and sediment supply, which in turn affect the morphology and course of rivers (Macklin et al., 2006; Benito et al., 2008). In general, these climatic changes can result in the reshaping of river landscapes over time, impacting ecosystems (Broothaerts et al., 2013; Sendek et al., 2021) and human activities (Winiwarter et al., 2013; Brandolini and Carrer, 2021). In particular, in urban settings, the interactions between humans and floodplains are complex and interconnected (Haase, 2003; Hohensinner et al., 2013a; Nießen, 2020). However, on a Holocene scale, a potential equilibrium state of river morphodynamics is under debate, and responses of external drivers are discussed to be non-linear (Elznicová et al., 2023).

Changes in floodplain dynamics during the Holocene, especially late Holocene climatic variations, have left terrain landforms and river channel patterns that are still preserved today (Schirmer et al., 2005; Schielein et al., 2011). The Little Ice Age (LIA; 1250–1860 AD), a period of relatively cooler and wetter climate in Central Europe (Büntgen et al., 2011b; Wanner et al., 2022) from the late Middle Ages to the 19th century, significantly influenced fluvial processes, driving increased fluvial erosion, lateral reworking, and aggradation in riverine systems (Macklin and Lewin, 2008; von Suchodoletz et al., 2022, 2024). However, the response of fluvial systems to climatic changes during the LIA seems to be variable both spatially and temporally (Rumsby and Macklin, 1996; Elznicová et al., 2023).

Apart from climatic variations, catchment-scale variability in land use, terrain openness, and geomorphological connectivity drive the fluvial system due to varying sediment supply and discharge peaks in frequency and magnitude; therefore human–environment interactions are decisively modifying fluvial dynamics (Dotterweich, 2008; Brown et al., 2009; Hoffmann et al., 2010; Ballasus et al., 2022; Dreibrodt et al., 2023; David et al., 2024; von Suchodoletz et al., 2024). Since at least the Middle Ages, most rivers in Central Europe have been subject to anthropogenic alteration (Hoffmann, 2010). The construction of mill races transformed tributaries and branches and brought them under anthropogenic control, or entirely new channels were created to harness hydropower. Hydropower facilities incorporating water wheels, ponds, diversion channels, and dams greatly influenced sediment transport and flow velocity (Walter and Merritts, 2008; Werther et al., 2021a). Even after the abandonment of active mills or weirs, geomorphological adaptation processes can still be observed (Vetter, 2011; Buchty-Lemke and Lehmkuhl, 2018). Rivers also played an important role as transportation routes, and timber rafting strongly influenced river morphology by removing obstacles and straightening river courses. Consequently, it is difficult to discern the individual impacts of human actions, climate variations, and inherent landscape system factors as forces of change (Knox, 2006; Macklin and Lewin, 2008; Candel et al., 2018; Notebaert et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2021).

The utilization of the rivers themselves can be assumed to be diachronic, as they provided access to water supply, hydropower, etc. (Werther et al., 2021a; Hardt and Lohse, 2025). Hence, a regulating impact on the courses of the rivers is likely, although only sparsely documented in pre-modern times. European-scale studies show the use of bio-engineered wooden structures for riverbank protection since the 19th century (Evette et al., 2009). However, 18th-century hydraulic engineers had already discussed several measures of bank stabilization, including the planting of river banks and the use of wooden structures (Silberschlag and von Hohenthal, 1756). Regarding pre-industrial riverbank protection, there is archaeological evidence from the Rhine River, where large-scale protections using stone packings and wooden stakes were found as early as in antiquity times (Gerlach et al., 2016). Along the Main and further rivers in Southern Germany, there is already evidence for riverbank protection using wooden stakes since the High Middle Ages (Becker and Schirmer, 1977; Pfäffgen and Weski, 2024). Furthermore, the construction of riverbank protection and its capacity is dependent on the economic and organizational strength of the owners (Gerlach, 1990). The riverbank protection measures were very likely implemented under monastic ownerships. Most of the lands in the study area belonged to the Leipzig monasteries until the Reformation, making specific riverbank protection measures probable (Gerlach, 1990). As technical measures, fascines (bushes and shrubs held together with willow wickerwork) are well known (Pfäffgen and Weski, 2024).

In the past, Leipzig's waterways were of interest to many scientists in both archaeology and history, not least because it was difficult to understand their formation (Grebenstein, 1959; Arnhold, 1964; Küas, 1976). Early research in Leipzig began with the Dähne family, who managed the city's waterworks in the 18th century. Their interest in the watercourses was already directed towards the city's water quality. At the beginning of the 20th century, the town historian Ernst Müller collected many sources on the city's water supply. In particular, he answered questions of water usage rights on the Pleiße mill race arising from medieval contracts (Municipal archive Leipzig, 0501, NL, Ernst Müller, Nr. 69). Later, the archaeologist Herbert Küas and the hydraulic engineer Georg Grebenstein used his collection to work on the question of the original courses of the rivers. According to the classification of Makaske (2001), the past water network in the Leipzig basin can be characterized as an anastomosing river system with a multitude of meandering sections. Later, the rives were used, transformed, and realigned, which makes reconstruction more challenging. Both attempted to create a map as a reconstruction of the medieval city, which included watercourses as a vital part of the city’s economy; e.g. mill races were dug to provide sufficient hydropower to operate mills and provide potable water (Grebenstein, 1959; Küas, 1976).

In recent historical research, the earliest churches and burgwards of the region were linked with the early medieval settlement pattern that is centred along the river courses between Merseburg and Taucha (west–east) and between Schkeuditz and Pegau (north–south) (Cottin, 2015b). The activities of Leipzig's monasteries and university in urban and suburban areas imply an early use of the watercourses by these organizations (Sembdner, 2010; Bünz and John, 2015; Gornig, 2023). However, more emphasis needs to be placed on the impact of these institutions on the rivers. Previous research on the water courses has thus shifted from questions of water quality to usage rights and to increasingly urgent questions of the origins of the city’s layouts and urban–rural interdependencies (Cottin, 2015a, b). The main findings are that the rivers were altered and modified in the Middle Ages, which caused issues with floods and droughts in the early modern period. The primary objectives of managing the water were to operate the water mills, which played a crucial role in providing food for the urban residents (Hardt and Lohse, 2025). In consequence, the question that arises is when and whether these human activities have caused a change in river dynamics, even in a floodplain with a complex system of natural water courses such as in Leipzig. By the end of the 15th century, a complex system of ditches, weirs, and mill races had been created, which was looked after, adapted, and expanded over centuries, for instance, through the establishment of a piping system begun in 1496 or by building a canal for timber rafting branching off from the Weiße Elster River near Pegau restructuring the Batschke River from 1608–1610 (Andronov et al., 2005). Today we observe a stable river water network with fixed courses.

In this study, we aim to address the following research questions:

- i.

How active and dynamic were the rivers in the Elster–Pleiße floodplain south of Leipzig during the last centuries, as determined through quantitative geomorphological survey based on a light detection and ranging Digital Terrain Model (LiDAR DTM)?

- ii.

When did the transition from a highly mobile river system to a more stabilized channel network occur, based on quantitative analysis of old maps?

- iii.

What were the primary drivers that influenced the stabilization of rivers and transformation of the floodplain?

Leipzig is located in the Leipzig Basin and belongs to the North German Lowlands, which received their main geomorphological features through glacial and periglacial overprinting in the Quaternary period (Eissmann, 2002; Denzer et al., 2015). The morphology of the wide valley is characterized by gravel terraces from the Saalian glaciation period and partly also from the Weichselian glaciation period. Pre-Holocene fluvial deposits underlie the younger sediments and are not visible at the surface (Eissmann, 2002). Outside the valleys, the terrain surface in the larger area exhibits localized remnants of Saalian terminal moraines manifesting as ridges and hills (Eissmann, 2002). The ground moraine plains are predominantly overlain by sandy loess (Haase et al., 2007; Lehmkuhl et al., 2021). Characteristic soil types in those areas are Cambisols, Albeluvisols/Luvisols, and Stagnosols (Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie, 2020).

Since the latter part of the 20th century, numerous researchers have concentrated on understanding the development of the Holocene floodplains associated with rivers near Leipzig (Neumeister, 1964; Händel, 1967; Tinapp, 2002; Fuhrmann, 2005; Tinapp et al., 2019; von Suchodoletz et al., 2022). Their research primarily examined major shifts in floodplain sedimentation, climatic variability, and catchment-scale human settlement dynamics across the Holocene. However, Ballasus et al. (2022) highlighted ongoing discussions regarding the spatiotemporal dependencies of human influence within terrestrial watersheds and the subsequent floodplain aggradation.

Positioned in the rain shadow of the Harz Mountains (Fig. 1A), Leipzig receives an annual rainfall of approximately 500–550 mm, with a slight maximum during the summer months. Recent years have witnessed a trend of increasing temperatures and occasional episodes of intense drought, influencing tree-ring growth patterns (Schnabel et al., 2021). In the headwater regions of the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers, annual precipitation reaches about 900 mm, with a pronounced peak in the summer.

The Weiße Elster River, stretching roughly 250 km and draining an area of about 2900 km2, is the main stream traversing the Leipzig Basin (MQ around 17 m3 s−1). Originating in the Czech Elster Mountains and discharging into the Saale River near Halle, this river is a third-order branch in the Elbe River network (von Suchodoletz et al., 2022). Around Leipzig, the Weiße Elster River merges with the Pleiße River (MQ around 2 m3 s−1), a lowland river currently measuring about 90 km in length, although it extended over about 115 km before 20th-century coal mining (Haikal, 2001; Tinapp et al., 2020). Its valley is notably narrower, about half the width of the Weiße Elster River's.

The study area is also crossed by two anabranches of the Weiße Elster River, the Batschke River, and the Paußnitz River, which form part of the river’s anastomosing network. The Paußnitz River originally drained into the Batschke River, which in turn drained into the Weiße Elster River, rather than following its present course into the Elsterhochflutbett. In the 1970s, the Paußnitz River's course was modified due to lignite mining around what is now Lake Cospuden, leading to the destruction of its former course (Fig. 1). Abstracted groundwater from dewatering of the mining area was directed into the Paußnitz’s remaining northern section. Today, the Paußnitz River receives water from the Weiße Elster River.

Unlike the Weiße Elster River floodplain (Mol, 1995; Tinapp, 2002; von Suchodoletz et al., 2022, 2024), which has been investigated more thoroughly, the sedimentary structure of the Pleiße River floodplain remains inadequately explored (Tinapp et al., 2019). Regarding the Pleiße River, flood loam deposits of approximately 2.5 m were identified, with only about 1 m accumulated since the Slavic era (Neumeister, 1964; Tinapp et al., 2019). Also, Tinapp (2002) noted increased flood loam accumulation starting around the beginning of the 9th century in the Weiße Elster floodplain. Regarding a standard Holocene floodplain sediment stratigraphy, the oldest Holocene sediments in the lower Pleiße valley are peat deposits that developed in small depressions of the Weichselian valley floor during the Preboreal period (Neumeister, 1964; Händel, 1967; Tinapp et al., 2019). Organic sediments in the same stratigraphic position are also known from the lower Weiße Elster River valley (Hiller et al., 1991; Mol, 1995; Tinapp, 2002), and organic deposition since that period is also known from other catchments in central Germany (Litt, 1992; Kirchner et al., 2022). Wetter conditions and higher groundwater levels in the valleys during the Preboreal probably resulted in the formation of many small peat layers on the Weichselian fluvial sediment base. On top of these, several layers of alluvial overbank fines exist, featuring intervals of diminished sediment accumulation or increased soil development. Typical soil types in the floodplains are Gleysols and Fluvisols with varying properties (e.g. mollic, cambic) (Haase et al., 2000; Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie, 2020).

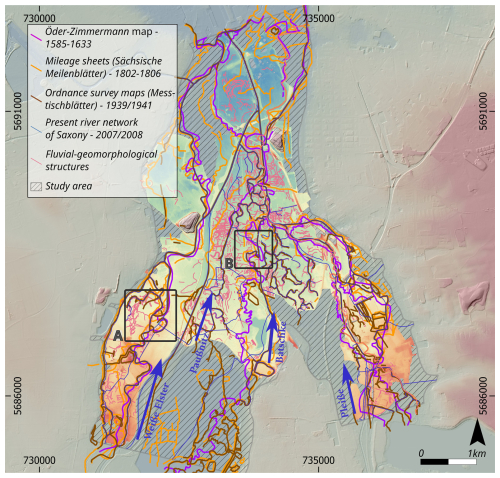

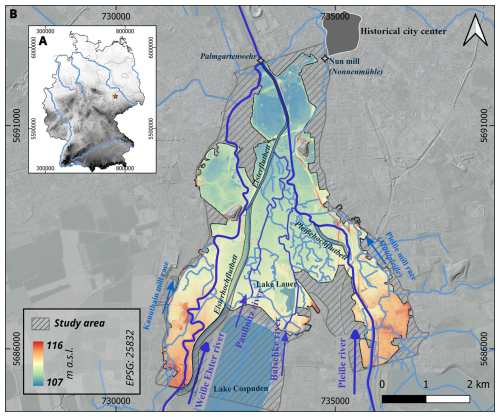

The study area (Fig. 1B) encompasses the floodplain in the southern region of Leipzig (ca. 20 km2). This floodplain extends up to 4 km in width and comprises the inundation zones of the Weiße Elster, Pleiße, Paußnitz, and Batschke rivers. The Weiße Elster and the Pleiße rivers form a watercourse junction that is accompanied by the Elster–Pleiße floodplain forest. We restricted our study area to the Holocene floodplain, as identified and delimited from the geological map, the lithofacies map, and the present topography (Haase and Gläser, 2009). To the north, the Palmgartenwehr, which marks the transition of the Elster flooding canal (Elsterflutbett) into the Weiße Elster River, defines the boundary. The southern boundary is marked by the post-mining Cospudener See and Markkleeberger See, beyond which lies a landscape heavily influenced by open-cast lignite mining (Haase et al., 2002; Berkner, 2019).

Fluvial geomorphological processes are a crucial key for analysing changes in land surface and land use patterns over time. For example, data from archaeological excavations and geological profiles, relating to anthropogenic and geological substrates, were used in quantitative modelling to depict the palaeorelief at 1015 AD of Leipzig's city centre (Grimm and Heinrich, 2019). Fluvial processes also created landscape segments with high value for nature conservation today. Currently, 13 % of the urban area of Leipzig is designated as a landscape protection area, with about half of these areas belonging to the special area of conservation (SAC; FFH – Flora-Fauna-Habitat) Leipziger Auensystem (Scholz et al., 2022). As a result, a significant portion of the areas within the floodplain is subject to special protection status and under a riparian forest cover, which helps to preserve surface structures. The southern floodplain forest (also known as Leipziger Ratsholz) has belonged to the city of Leipzig since 1543 AD. Previously, it had been expanded and maintained by the Augustinian monastery of St. Thomas for over 3 centuries (Lange, 1959; Rehm, 1996). The forest history of the 19th and 20th centuries shows the spatial consistency of forest distribution. Only the change in management from the former coppice with standards to high forest management in the second half of the 19th century influenced the tree species composition (Gläser, 2005; Haase and Gläser, 2009). The long-term continuity of the forest stand, the diversity of tree species, and the history of land use establish the Leipzig floodplain forest as a hotspot of biodiversity with national significance (Wirth et al., 2021).

Figure 1Geographical context of the study area. (A) Location of Leipzig within Germany marked by a red star. 20×20 m Digital Terrain Model (DTM) data from Sonny (2021). (B) Local context of the Weiße Elster–Pleiße floodplain south of Leipzig. Dark-blue lines indicate major rivers, and bright blue lines indicate anabranches and anthropogenic channels. (1×1 m LiDAR DTM by GeoSN, 2018). EPSG:25832.

3.1 Data

3.1.1 Digital geodata

-

Digital Terrain Model (DTM). High-resolution airborne laser scanning data were provided by the State Office for Geoinformation and Surveying Saxony (GeoSN, 2025). We used the derived 1×1 m spatial resolution DTM, which was recorded on 13 and 14 February 2018 (Table 1). It has a height accuracy of ±0.2 m and is suitable for the mapping of fluvial geomorphological structures (e.g. former channel positions, ridge-and-swale structures, levees, crevasse splays, backflow channels) (Kokalj and Hesse, 2017).

-

Digital orthophoto (DOP). A high-resolution aerial image (0.2×0.2 m spatial resolution) was provided by the State Office for Geoinformation and Surveying Saxony (GeoSN, 2025). The DOP is also available in 2×2 km grid cells, and the recordings from the study area cover the period between 21 and 27 April 2021 (Table 1). We used the DOP for the manual verification of mapped structures, for example, to identify current water bodies.

-

Open street map (OSM). The open street map layer was used to manually verify that mapped structures were not incorrectly assigned to anthropogenic tracks and paths. For this purpose, an XYZ-tile integration (Table 1) of OSM with continuously updated data was used (OSM, 2021).

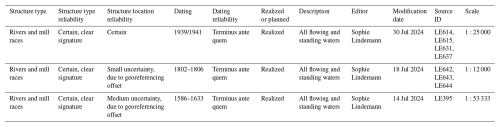

3.1.2 Old maps

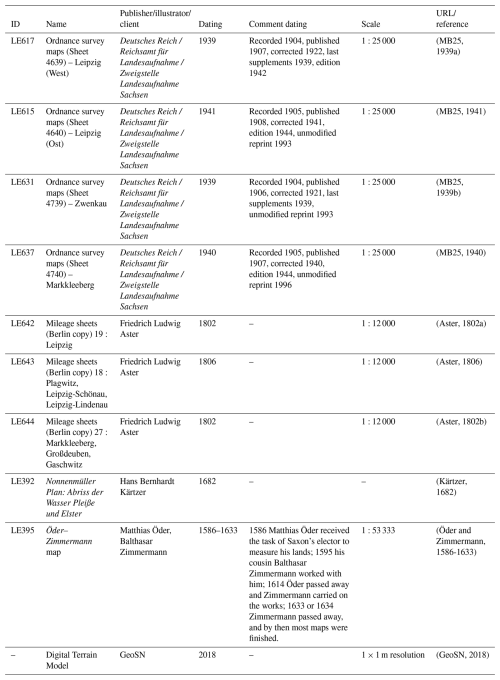

The purposes of the variety of old maps that show Leipzig and its surroundings differ considerably over the course of time (Ebeling, 1999; Schneider, 2006; Renes, 2016). Starting with first land surveys in the 16th century, which were financed by the Saxon rulers to measure their territories, the maps of the 17th and 18th century contain detailed views of the city, which usually include the rivers, but lack detailed sketches of the mills or plans of the entire catchment of the rivers. However, most of them are not drawn geometrically. With the help of modern land surveying techniques, the first precise maps in a geographical sense emerged in the 19th century. This way, maps were created either for detailed views on river structures or for overviews of whole countries (Witschas, 2002; Meyer, 2007). For this study, we have chosen the maps that offer the most comprehensive overview of the rivers in the floodplain and are the most accurate in geodetic terms. The Öder–Zimmermann map of Leipzig is a coloured, hand-painted map. The basis for this map was a land survey of the Saxon elector August I. As the elector had a penchant for cartography, his cartographers were equipped with the techniques and knowledge of the time. In 1585, his successor Christian I ordered Matthias Öder to create the map discussed. In 1595, Öder hired his cousin Balthasar Zimmermann for support. After Öder’s passing, Zimmermann continued working on the map until his death in 1633 or 1634, hence the name Öder–Zimmermann (Wiegand, 2014). This is why the Öder–Zimmermann map is geometrically accurate and remained unrivalled in its precision until the late 18th century (Blaschke, 2002). The Öder–Zimmermann map was drawn in 1:53 333. The next selected maps are the mileage sheets (Sächsische Meilenblätter, Berliner Exemplar) of Saxony, which were produced for the Saxon electors between 1780 and 1806. The maps (map sheets 18, 19, 27) showing the study area are from 1802 to 1806 and were drawn with a spatial scale of 1:12 000. This hand-printed map is digitally accessible and importable into a geographic information system (GIS). For easy reproducibility, we have chosen the georeferenced WebMapService (WMS) version (Historischer Dienst Sachsen, 2007). The ordnance survey maps (Messtischblätter; 1:25 000) were created between 1887 and 1928 for a land survey by the Royal Saxon General Staff (until 1918) and by the German Reich Office for Land Survey Saxony (after 1918) (GeoSN, 2025). The maps covering Leipzig (sheets 4639 and 4640) originate from the renewal series of the 1930s (sheets that cover Leipzig were first drawn in 1907/1908 and updated in 1939/1941), after the Elsterflutbett and Elsterflutbecken (both artificial water retention basins) had been built. As an additional old map, we refer to the map called the nun's miller survey (Nonnenmüllerplan; Table 1), which was created in 1682 by the miller of Leipzig's Nonnenmühle, a mill that once belonged to the nunnery of St. George. This old map is not suitable for georeferencing and will therefore not be further quantitatively evaluated, but it does show the entire study area. It has not yet been included in any historical study, apart from a visualization in a work on the floodplain depicting the rafting site south of the city (Liebmann, 2023). The map has an imprint claiming that it shows the Pleiße and Weiße Elster rivers with their mills, weirs, meadows, and forests between the city of Leipzig, Connewitz, Großzschocher, and the Rosental (Table 1). The most important features of this map are the coloured depictions of the forests, meadows, and rivers surrounded by rows of tree to explore the early modern landscape.

(MB25, 1939a)(MB25, 1941)(MB25, 1939b)(MB25, 1940)(Aster, 1802a)(Aster, 1806)(Aster, 1802b)(Kärtzer, 1682)(Öder and Zimmermann, 1586-1633)(GeoSN, 2018)3.2 Methods

3.2.1 Digital geomorphological survey

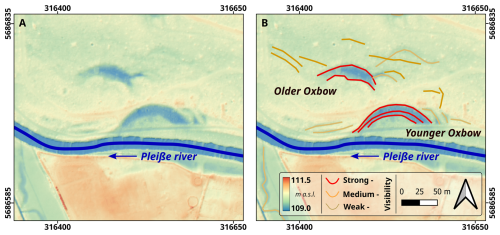

Geomorphological structures were visualized using a hillshade of the DTM with contrast enhancement by 2-fold exaggeration (Kokalj and Hesse, 2017). Furthermore, we used the local cumulative cut stretch to flexibly map different topographic areas. Smaller paths and trails can have a strong similarity to river channels in the DTM and hillshade. To distinguish them from each other, we used the OSM, where official roads and (sometimes unofficial) paths are marked. In addition, we included indications of unofficial trails or paths from the DOP. Relics of buildings or other construction structures were also excluded in this way (Schmidt et al., 2018). The mapping was carried out using three map classes based on the size and subjective distinctness of the structure (classes: strong, medium, and weak visibility; see example in Fig. 2). We focused on the structural diversity that is directly related to fluvial dynamics: natural levees, crevasse channels and splays, meanders and oxbows, and backflow channels (Schirmer et al., 2005; Wierzbicki et al., 2013, 2020; Beckenbach, 2016; Kirchner et al., 2018; Teofilo et al., 2019).

3.2.2 Georeferencing and vectorization of old maps

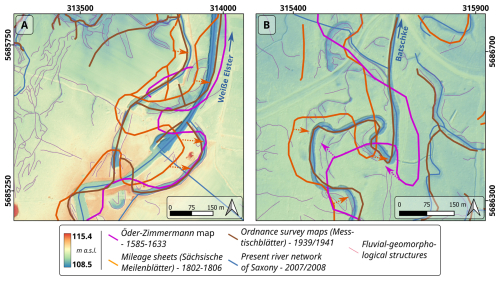

The 20th-century ordnance survey maps and the early 19th-century mileage sheets were digitally available as georeferenced raster layers (Fig. 3). We verified the accuracy and precision against additional geodata (DTM, OpenStreetMap, etc.). Only the early 17th-century Öder–Zimmermann map had to be processed. We georeferenced this old map using the regressive–iterative GIS reconstruction method (Hohensinner et al., 2013b) by using riverine structures (rivers and mill races), hydraulic constructions (weirs and mills), and infrastructure (roads and bridges) to project the maps onto a coordinate system in a GIS (Quantum-GIS) (see Table 1). The georeferencing procedure follows the standardized guideline including metadata storage (Schmidt et al., 2024). Following the principle “two steps back, one step forward” (Hohensinner et al., 2013b), both the ordnance survey and mileage sheets helped to determine the locations of these fixed points on the Öder–Zimmermann map for georeferencing. In this approach, one moves step by step back in time, in order to be able to validly use the fixed points and their location from younger maps to older maps. At the same time, the mapped features get revised from old to young. The vectorization of the rivers on the old maps was likewise carried out in a standardized form (Schmidt et al., 2024). For reasons of comparability, the rivers were drawn as lines (Table 2). As a result, we obtained four layers depicting the rivers at a certain point in time (1585–1633, 1802–1806, 1939–1941, today).

Table 2Metadata structure of vectorized map elements. Table structure based on the template from Schmidt et al. (2024)

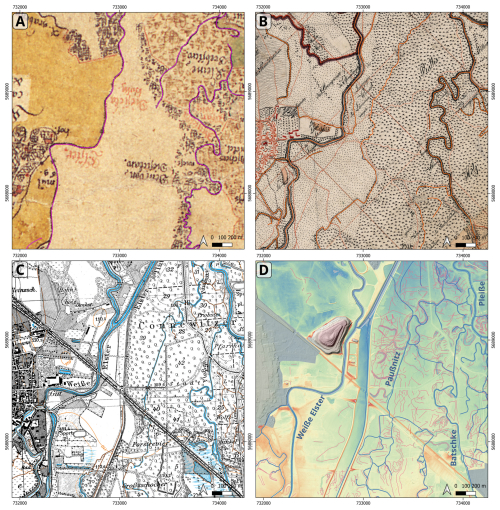

Figure 3Sections of the study area with georeferenced old maps and the LiDAR DTM (Table 1) with vectorized rivers and channels (Table 2). (A) Öder–Zimmermann map (1585–1633). (B) Mileage sheets (Meilenblätter von Sachsen, Berliner Exemplar, 1802–1806). (C) Ordnance survey maps (Messtischblätter, 1939/1941). (D) LiDAR DTM with mapped fluvial geomorphological structures. EPSG:25832.

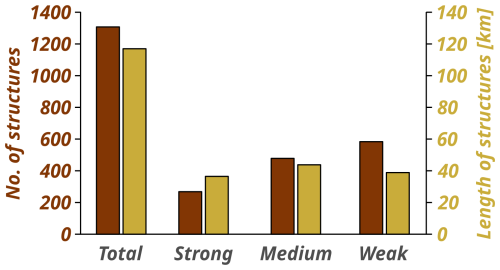

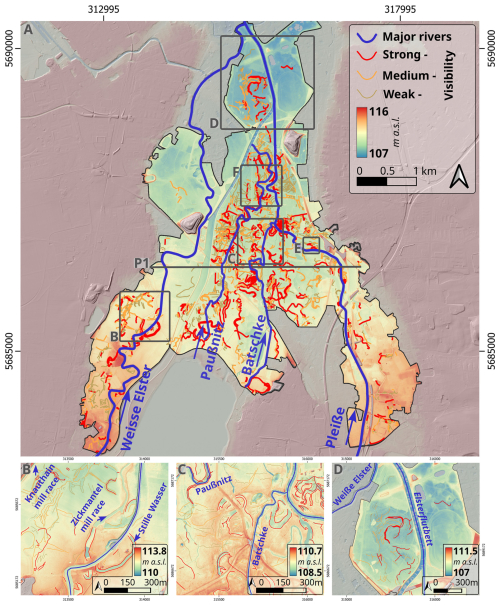

4.1 Fluvial geomorphology

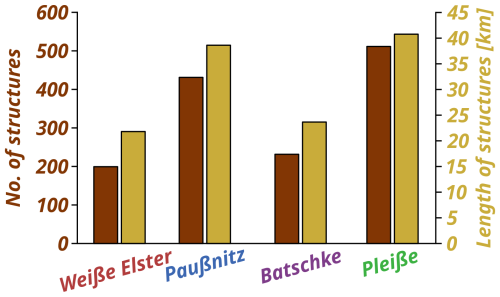

In total, 1306 geomorphological structures with an overall length of 116 km were mapped in the study area (Fig. 4A). In particular, the central area between the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers shows a high density of natural fluvial–geomorphological structures. In contrast, the peripheral areas of the floodplain are more heavily modified due to anthropogenic use (park, recreational areas, building areas, infrastructure, etc.), so natural fluvial structures often become too blurry for recording purposes (Fig. 5).

The majority of all structures were found along the Paußnitz and Pleiße rivers. However, compared to the absolute lengths of the rivers (Table 3), the relative lengths of the fluvial–geomorphological features along the Batschke River are higher than along the Pleiße River. Nevertheless, the Paußnitz River floodplain stands out, as both the absolute and relative proportions of structures are the highest. The percentage of structures with medium to weak visibility is the highest, whereas the relative number of strong-visibility structures is rather low (Fig. 6). The floodplain areas surrounding the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers are slightly elevated by 0.5 m compared to the central section of the Elster–Pleiße floodplain (Fig. 5). The central section is traversed by the Paußnitz and Batschke rivers.

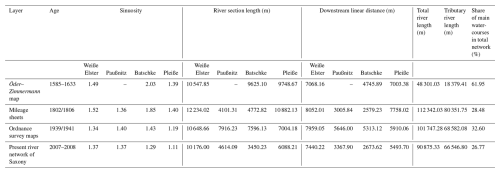

Diachronic river length calculations depend on the georeferencing accuracy of the old maps (Tables 1 and 3). Hence, relative comparisons are more robust than absolute values. This is especially evident for the tributary river lengths, which refer exclusively to side channels that are not part of the main courses. Therefore, the values are particularly smaller in the Öder–Zimmermann map. Reconstructed sinuosity decreases over time for all rivers, with the strongest decline observed for the Batschke River.

Figure 4Classified vectors of the geomorphological survey based on the LiDAR DTM. (A) Total study area with main anabranches. Positions of the enlarged sections are indicated with grey boxes. The location of the topographic cross-section of P1 is shown in panel (A). (B) Enlarged section of the Weiße Elster River zone with remnants of palaeomeanders. (C) Enlarged section of the Batschke zone with natural levees and oxbows. (D) Enlarged section of the Pleiße River zone (post-confluence with the Batschke River) with remnants of palaeomeanders. The legend for vectors from panel (A) is valid for panels (A)–(D). The location of square E refers to Fig. 2. The location of square F refers to Fig. 7. Background in (A)–(D): 1×1 m LiDAR DTM (GeoSN, 2018). EPSG:25833.

Table 3Sinuosities and river metrics based on the vectorized old maps and the present river network.

4.1.1 Weiße Elster River

The floodplain areas along the Weiße Elster River have a strong anthropogenic overprint, so relatively few natural structures can be found (Fig. 4A). However, two sections stand out. At one location, the recent Weiße Elster River is enclosed by the Zickmantel mill race (Zickmantelscher Mühlgraben) and the Stille Wasser, which occupy a former meander loop of the Weiße Elster River (Fig. 4B). Both have the distinct curved shape of an old river channel. The western part of that former meander loop (now known as Zickmantel mill race) was part of the water supply for the Knauthain mill race. The Zickmantel mill race begins west of the Weiße Elster River and flows northwest into the Knauthain mill race, with a generally straight path. Between the Knauthain mill race and the Weiße Elster River, further meandering structures are visible. Today, the Weiße Elster River follows a straighter course further downstream, intersecting older channel features, mostly in forest-covered areas, with some in allotment gardens (Fig. 4A). The mapped structures along the Weiße Elster River are of strong visibility and are likely a meander bend of its former river course. Most of these oxbows are filled with water today (oxbow lakes). The widths of these structures range from 20 to 25 m. The old oxbows exhibit typical meandering forms, featuring steep cut banks and smooth point bars, which indicate natural fluvial processes. Along the old meanders, natural levees (ca. 0.5 m raised above the floodplain) can be found, indicating relatively low lateral dynamics. Additionally, at one location, remnants of a crevasse splay can also be found. The weak- to medium-visibility structures indicate relatively small backflow channels. However, preservation is poor due to anthropogenic alteration.

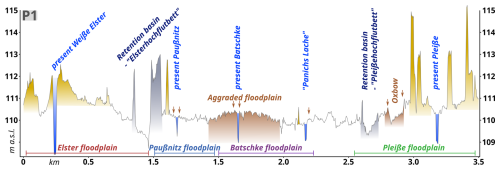

Figure 5Topographic profile of the cross-section before the confluence of the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers based on the 1×1 m LiDAR DTM (GeoSN, 2018). The yellow areas indicate modern infrastructure, including man-made dams that alter the topography. The grey areas indicate both 20th-century flood protection constructions (Elsterhochflutbett and Pleißehochflutbett), including the retention basins and their dams. The brown areas highlight notable geomorphic features mentioned in the text. Small arrows mark natural levee positions. The location of the cross-section P1 is shown in Fig. 4A.

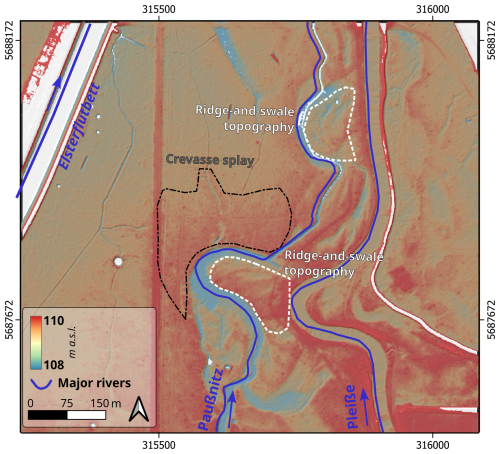

4.1.2 Paußnitz River

Almost the entire Paußnitz floodplain area is forest-covered today. Due to its conservation-effect, the diversity and number of fluvial–geomorphological structures are therefore very high in the area. At least two former river courses are visible. These structures connect partly to the current course of the Paußnitz River, indicating an alignment over time (Fig. 3D). In the southern region, at least five old meander structures of the Paußnitz River are visible. The general appearance of the Paußnitz is characterized by old meander structures, which also exhibit a point bar morphology in many places. Large bends of the oxbows reveal steep cut banks and gentle point bars, with bed widths ca. 21–22 m, similar to the modern Paußnitz. A fan-shaped structure along the Paußnitz likely formed from a natural levee breach (crevasse splay; Fig. 7). Natural levees can be found along all former meander structures with elevations of ca. 0.4 m raised above the floodplain, indicating relatively low lateral dynamics. At the same time, the point bar positions of the former meanders are characterized by a ridge-and-swale-structured relief, indicating active lateral dynamics before the formation of the levees. Historical interventions in the 20th century, influenced by mining and conservation efforts, shaped the current pathway of the Paußnitz River, altering its natural flow and morphology.

4.1.3 Batschke River

Today, the Batschke River begins in the far south near the northern shore of Lake Cospuden. From there, it flows relatively straight northward, passing through the southern floodplain forest near Lake Lauer (a former gravel pit) and connecting with it. Afterwards, it has small meander structures before flowing straight for ca. 1 km and finally flows in a meandering pattern into the Pleiße River. The area between the Batschke and the Pleiße rivers is defined by the southern floodplain forest and an extensive network of unnamed ditches (Figs. 1, 8). In the DTM, at least five former meander loops can be identified in the area of the currently straightened section. North of the straightened section, further ditch systems are active and link to the Paußnitz River, which later drains into the Weiße Elster River.

At the Batschke’s confluence with the Pleiße River, a broad complex of channels with prominent meanders is visible (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, older structures appear intertwined, crossing paths with one another and also with the current Batschke River course, making it difficult to trace their connections. The most distinct feature is a loop structure directly south of the confluence. The main course of the Batschke River was modified into a timber rafting ditch in the early 17th century, with timber rafting ceasing in 1864. Since then, the Batschke River's remaining course has been a stable, straight channel. While meander-like bends are highly visible in the area, detailed ridge-and-swale structures are slightly less pronounced, likely due to the interference from very dense vegetation and thus a poorer Digital Terrain Model. The subtle asymmetry of the cross-section and indistinct cut bank and point bars might indicate that this channel has undergone significant sedimentation since the meander structures were abandoned. Natural levees (up to 0.6 m raised above the floodplain) are clearly visible along almost all former courses of the Batschke River. Moreover, several crevasse splays and crevasse channels are recognizable, and, overall, the entire area of the Batschke floodplain is vertically aggraded by up to 0.5 m compared to the floodplains of the Paußnitz and Pleiße rivers (Fig. 5). The peripheral areas of the floodplain along the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers are heavily overprinted (Fig. 5, yellow and grey areas) and, apart from artificial dams and infrastructure, have only a slightly higher floodplain level than the inner area between the Batschke and Paußnitz rivers. However, in this inner area, the Batschke floodplain can be seen to rise above the level of the Paußnitz floodplain. Besides the main course of the Batschke River, several smaller channel structures are visible. These structures vary in width (5 to 30 m), especially between the broader channels west of the Pleiße River and the narrower ones to the east, suggesting these may have been separate rivers that merged over time. This branching pattern resembles an anastomosing river system.

4.1.4 Pleiße River

Significantly fewer structures can be found in the southeastern part of the study area. The Pleiße floodplain area is heavily influenced by human activity. Large areas are built up with buildings and infrastructure and are unsuitable for DTM analysis. As a result, hardly any structures are preserved, especially in the southern part of the study area. Only small backflow channels can be identified. An important hydrological influence is the branch of the southern Pleiße mill race (Mühlpleiße; Fig. 1) from the Pleiße River. In the area where the Pleiße River enters the wide floodplain between the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers, smaller and larger former courses can be recognized. In the area of the present Pleiße River retention basin (Pleißehochflutbett), a large-scale meander loop with a pronounced cut bank is preserved (diameter over 300 m; Fig. 5). Smaller remnants of meander loops appear with varying intensity (Fig. 2). The area around the Batschke River confluence is outstanding for its dense network of structures that can also be seen on the eastern side of the Pleiße River. It indicates an additional inflow from a Pleiße River branch or another river (Fig. 4C, northeastern part). Subsequently, the larger structures decrease to the north, and only smaller backflow channels can be seen. Generally, natural levees are not visible along the Pleiße River; thus there are no crevasse splays.

4.2 Old maps

The ordnance survey maps from the 20th century show that several sections of the Weiße Elster, Pleiße, Paußnitz, and Batschke rivers have been straightened (Fig. 3B–C). Those sections that have not been straightened show exactly the same meandering structures as the mileage survey (1802–1806) and the Öder–Zimmermann map (1585–1633). Hence, it was surprising to find that the 20th-, early 19th-, and early 17th-century maps show only slight channel shifts. In particular, the position and shape of the meander bends are nearly the same on all maps. Minor offsets in the representation of the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers are only evident at a few locations. They can be found in the southern part of the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers in the study area. Two meander bends seem to be more curvy in the mileage sheets, compared to the Öder–Zimmermann map. Most of the recognizable differences can be traced back to historical anthropogenic influences. For instance, the Elsterflutbett is a newly added structure from the year 1928 on the ordnance survey map. This artificial retention basin is derived from the Weiße Elster River and leads to the middle of the floodplain, where it meets another channel that is diverted from the Pleiße River. The Batschke River was converted into a rafting ditch in the early 17th century. On the Öder–Zimmermann map, the river has rather large meandering bends. The early 19th-century mileage survey, however, reveals a redirection and straightening in parts of this stream for the purpose of timber rafting, whereby the older river course was abandoned. The Paußnitz River is depicted as a very short stream on the Öder–Zimmermann map and is not drawn in the entire study area. In the mileage survey and the ordnance survey maps, this river is completely drawn. In the 19th century, the Paußnitz River was depicted as a slightly meandering river, whereas, in the 20th century, a straightened course is already recognizable. The quantitative analysis of river networks of all vectorized old maps shows a general decrease in the sinuosity of the main rivers (Weiße Elster, Pleiße, Batschke, and Paußnitz rivers) over time (see Table 3). The Batschke River has the highest sinuosities compared to the other main rivers. In general, the representation of smaller anabranches on the Öder–Zimmermann map is relatively sparse. The level of detail concerning the depiction of smaller branches and tributaries increases over time, observed by decreasing values of the shares of main courses in the total river network.

5.1 Reliability of old maps

The major rivers in the study area, vectorized from old maps, show minor diachronic changes in channel positions (Fig. 9). Although the georeferencing precision is limited, the shape and general positions of the river courses are comparable (Fig. 10, Table 1). In addition, Zielhofer et al. (2022) already worked with georeferenced old maps in the Havel River region. Despite slight georeferencing deviations, they were able to understand changes in the river system through quantitative analyses. Channel positions of the Havel inner delta could be reconstructed and quantitatively analysed in relation to diachronic hydrological changes. Slight georeferencing deviations could be neutralized by relative comparisons because relative spatial relationships were more meaningful than the absolute location. The present study likewise focuses on relative changes rather than on absolute positions. The elements in the Öder–Zimmermann map were measured field-based and represented using contemporary methods (Wiegand, 2014). Although trigonometric precision is not to be assumed, the internal positional accuracy of the map seems evident. The mileage sheets were produced under the direction of Friedrich Ludwig Aster as part of the electoral Saxon topographical survey (Zimmermann, 2006). No older maps were redrawn; instead, all landscape elements were newly measured using geodetic triangulation with a theodolite (Brunner, 2007; Walz and Schumacher, 2011). The new surveying of topography, along with cultural landscape elements at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, is based on the Prussian original survey (Urmesstischblätter) and was likewise newly recorded using triangulation and resulted in the Ordnance survey maps (Messtischblätter) (Walz, 2002; Lorek and Medyńska-Gulij, 2020). The maps utilized have been independently surveyed, ensuring that the georeferenced and vectorized river courses are distinct and autonomous.

The utilization of old maps to derive past river courses from old maps and discuss them in a spatiotemporal context is a common procedure, proven in various catchments in Central Europe (Schielein, 2010; Hohensinner et al., 2013a; Elznicová et al., 2021; Werther et al., 2021b; Zielhofer et al., 2022). In recent years, their use for reconstructing water landscapes has increased (Hohensinner et al., 2013a; Zlinszky and Timár, 2013; Zielhofer et al., 2022). In addition, the spatial–temporal resolution allows a detailed approach to landscape development (Hohensinner et al., 2013b; Werther et al., 2021b).

Figure 10Vectorized river and channel positions from the old map collection (Table 2) and the geomorphological survey, which is based on the LiDAR DTM (see Fig. 3). (A) Enlarged section of the Weiße Elster floodplain. (B) Enlarged section of the Batschke floodplain. Arrows with dotted lines mark potential offsets of the vectorized channel positions induced by map trigonometric quality. The location of the sections is shown in Fig. 9 as squares A and B. Background: 1×1 m LiDAR DTM (GeoSN, 2018). EPSG:25833.

5.2 Meander migration through time

Despite the construction of mill races in the Middle Ages in the study area (Hardt and Lohse, 2025), the river sections largely follow stable, quasi-natural courses over time (Fig. 9). Conversely, abandoned river channels may have occasionally been integrated in mill race constructions. The accompanying natural levees along most of the river sections in the present study indicate positional river course stability, and the mapped fluvial geomorphological structures, such as palaeomeanders and oxbows, reveal older river courses. The older, more active anastomosing river system with meandering branches predates the oldest map (Öder–Zimmermann map 1585–1633). Interestingly, the diversity and distinctiveness of the mapped fluvial–geomorphological structures have been preserved, indicating no massive sedimentation has occurred since.

Sedimentological studies ca. 80 km south of the study area, at both the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers, show lateral dynamics of the Weiße Elster River for the last 400 years (Tinapp et al., 2019; von Suchodoletz et al., 2022, 2024). An increased meandering has been observed in other rivers of Central Europe for the last millennium (Candel et al., 2018; Elznicová et al., 2021). In the catchment areas of the Rhine and Danube rivers, two Holocene phases of river terrace formation are reported, which fall into the last 500 years (Schellmann, 1994; Schirmer et al., 2005; Schielein et al., 2011). Although the stratigraphic record in fluvial systems is fragmentary (Durkin et al., 2018), preservation percentages of sedimentary facies through time in meandering rivers can be quantified (Elznicová et al., 2023). The decline of active meanders, in turn, is associated with increasing direct anthropogenic influence in different catchments (Vayssière et al., 2020; Elznicová et al., 2021, 2023). In particular, weirs and other structures of hydropower use are discussed to prevent the activation of the hydrodynamic system (Buchty-Lemke and Lehmkuhl, 2018; Vayssière et al., 2020). In our study area, rivers that did not have specific hydropower facilities (weirs, mills, etc.) were also affected by the decline of active meanders (Batschke and Paußnitz rivers). However, there is a potential for indirect influence via the connectivity with neighbouring associated waters through the anastomosing river system.

In general, the migration of meanders is initiated by impulses acting on the banks (van de Lageweg et al., 2014). The erosion effect is therefore dependent on the stream power during flood events, especially during bankfull discharge (Kleinhans and van den Berg, 2011). Besides the analysis of specific decades in the early modern period (Hardt and Lohse, 2025), there are no comprehensive data on the long-term flood history of the region. A high-resolution chronicle of historical flood events would be a prerequisite for a better understanding of stream power variability over time. At the same time, other variables affect effective lateral erosion. Sediment cohesiveness and thickness, as well as the existence of a protecting vegetation cover, strongly influence the bank erodibility (Kleinhans and van den Berg, 2011; Candel et al., 2018).

The aggradation of cohesive sediments may be an important factor for the decline of an active meandering river in the study area. The thickness of sedimentary units (overbank fines) significantly influences its cohesiveness and susceptibility to lateral erosion (Julian and Torres, 2006; van Dijk et al., 2013). Today, 2.5 m thick fine-grained floodplain deposits can typically be observed in the study area (Graubner and Schmidt, 2025), with the floodplains of the Weiße Elster River and its large anabranches, the Batschke and Paußnitz rivers, characterized by thicker deposits than the Pleiße floodplain. A medieval colluvium that lies in the convergence area with the floodplain of the Weiße Elster River is covered by overbank fine sediments, which provides an initial clue for the chronostratigraphy (Tinapp et al., 2008). According to this finding, in the last 1000 years, approximately 1 m of overbank fines has been deposited. If we cautiously assume linear accumulation, the mean thickness in 1600 was on average ca. 0.5 m below their current values. Therefore, we assume an overbank fine sediment thickness of 1.5 to 2 m at the beginning of the 17th century.

Another factor is the grain size distribution, notably the clay content (Julian and Torres, 2006; Grabowski et al., 2011). The overbank fine sediments in the Leipzig Basin are characterized by loamy clays, with clay contents up to 50 % being common (Neumeister, 1964; Kirsten et al., 2022). The oldest floodplain deposits consist of a very clayey sediment but are covered by siltier sediments (Neumeister, 1964; Händel, 1967). Generally, the clay contents increase in the sediment sequences in the younger deposits.

Sediment supply from the catchments plays a significant role for the delivery of overbank fine sediments over time (Houben et al., 2013; von Suchodoletz et al., 2024). The mid-mountain range of the Weiße Elster catchment is susceptible to soil erosion due to increasing deforestation since the Middle Ages (Kaiser et al., 2023; Feeser et al., 2024). Colluvial deposits have formed since the 15th century and indicate sediment supply from the slope to the tributaries (Kaiser et al., 2021). Consequently, the silty to clayey sediments within the study region exhibit good conditions regarding bank stability (Julian and Torres, 2006). Hence, the stabilization of river courses may have been driven by decreasing erodibility due to gradually increasing clay content and increasing thickness over time. An intrinsic shift from active meandering to stable river flow cannot be ruled out. However, von Suchodoletz et al. (2022, 2024) found evidence of active meandering patterns approximately 80 km upstream on the Weiße Elster. Thus, the stabilization of the rivers in the Elster–Pleiße floodplain cannot be explained solely by internal system processes.

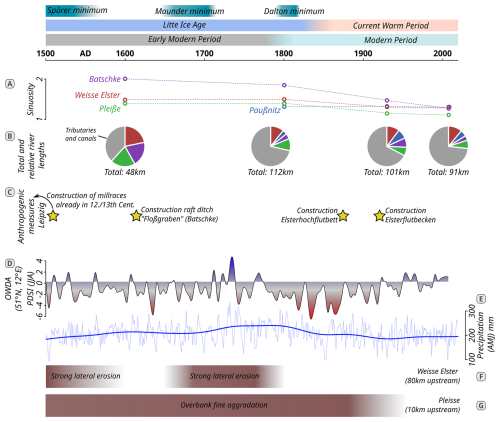

Figure 11Timeline of quantitative river network changes in the study area and comparison with main anthropogenic alteration of the river network, palaeoclimatological data, and fluvial geomorphological pattern. (A) Sinuosity of the four studied rivers based on the old map (Table 3). (B) Total and relative river lengths and further small stream values (Table 3). (C) Major river engineering works in the study area. (D) Drought severity index from the Old World Drought Atlas (51.22–51.42° N, 12.23–12.5° E) (Cook et al., 2015). (E) Spring precipitation reconstruction for Central Europe (Büntgen et al., 2011b). (F) Fluvial geomorphological pattern of the Weiße Elster River (ca. 80 km upstream of the study area) (von Suchodoletz et al., 2022, 2024). (G) Fluvial geomorphological pattern of the Pleiße River (ca. 10 km upstream of the study area) (Tinapp et al., 2019).

5.3 Hydroclimatic variability

Hydroclimatic variability strongly affects riverbank erosion and stream power, and the timing and intensity of precipitation and spring snowmelt events can be key drivers (Julian and Torres, 2006). During the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA; 950–1250), temperatures were about 1–1.5°C higher compared to the mean from 1190 to 1970 AD (PAGES 2k Consortium, 2013), whereas the “Little Ice Age” (LIA; 1500–1800) was a period marked by colder and wetter conditions, followed by the “Modern Optimum” characterized by rising temperatures due to industrialization (Mann, 2002; PAGES 2k Consortium, 2013; Herrmann, 2016). Regional reconstructions based on tree-ring growth models provide insights into Central Europe's climate history (Büntgen et al., 2011a), but there are no specific hydroclimatic reconstructions for the Leipzig region over the last 500 years.

For the Little Ice Age, studies indicate maximum spring to summer precipitation, while the Old World Drought Atlas shows increased, rather short-term summer droughts and wet phases for the same period (Büntgen et al., 2011b; Cook et al., 2015). A regional speleothem record from Southern Germany follows the precipitation reconstruction from tree-ring analysis (Kluge et al., 2023). However, the climatic impacts of the LIA in Central Europe are discussed to be generally variable (Wanner et al., 2022). Floodplain sediment archives from central Germany reveal both lateral erosion and overbank sedimentation phases during the Little Ice Age (Tinapp et al., 2019; von Suchodoletz et al., 2024) (Fig. 11). Moreover, a meta-study of several German river catchments shows relatively high river activities (represented by overbank fines and sands/gravels facies) for the last centuries (Hoffmann et al., 2008). In a pan-European context, the sedimentological data show that the rivers do not behave uniformly; rather, the response to climatic changes of the Little Ice Age (LIA) is spatially highly variable (Rumsby and Macklin, 1996; Brown, 2002; Pears et al., 2023).

Since a suitable regional hydroclimatic reference curve is lacking and Central European reconstructions show limited variability and do not resolve regional events, a hydroclimatic forcing of our findings cannot be assessed. Instead, we emphasize intrinsic fluvial dynamics together with specific anthropogenic interventions, which are discussed in the following sections.

5.4 Chronology of river use

Different phases of floodplain and river use can be distinguished in Leipzig, which are part of path dependencies in the consideration of a fluvial anthroposphere (Werther et al., 2021a). Since the 10th century, the early urban agglomeration of Leipzig emerged as a stronghold on a ridge near the confluence of the Pleiße, Weiße Elster, and Parthe rivers. This castle secured the route over the rivers to the important Merseburg (Hardt, 2015; Hardt and Lohse, 2025). The floodplain served as a resource for timber, food, and water supply. Leipzig’s monasteries were established before the 13th century (Bünz, 2015). It is likely that these monasteries developed the water engineering measures to build the mills with the help of weirs and mill races (Hardt and Lohse, 2025). The construction of the mill races for the water supply of the city mills dates between the 12th and 13th centuries (Fig. 11C; Grebenstein, 1959, 1995; Hardt and Lohse, 2025). The mills further south, which are connected to the Pleiße and Weiße Elster rivers via the southern Pleiße mill race (Mühlpleiße; Fig. 12) and the Knauthain mill race (Knauthainer Elstermühlgraben; Fig. 12), also date back to this period (Cottin, 2015b; Gornig, 2023).

The construction of the nun mill (Nonnenmühle; Fig. 1) by the nunnery of St. George is only mentioned in Leipzig’s sources in 1287 (CDS II 10, No. 23, p. 16). The alluvial forests further away from the city are mainly owned by the monastery Augustiner-Chorherren-Stift zu St. Thomas and by the nunnery of St. George (Gornig, 2023). Under these orders, these forests were likely to be more protected from over-exploitation. For example, St. Thomas obtained an injunction against the city council in the year 1373 regarding citizens unlawfully cutting wood in their forests (CDS II 9, p. 109ff.).

Major river transformations of the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers are therefore likely to have been completed by the 13th century. The next phase of larger changes to the rivers was initiated in the 16th century, when the Weiße Elster rafting ditch (Elsterfloßgraben) was developed. The use of the forests near the city exceeded the timber supply, which is why other sources further upstream were used to transport timber (Denzer et al., 2015). These developments resulted in the construction of a branch of the Weiße Elster rafting ditch that reached Leipzig in the early 17th century. Therefore, the Batschke River was converted into a straighter canal (Fig. 11; since then officially called Batschke-Floßgraben) (Andronov et al., 2005).

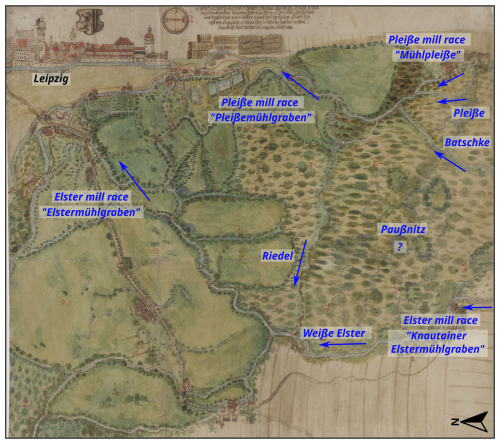

The evolution of the Paußnitz River is rather difficult to understand. This river is mentioned as part of a forest and was therefore owned by the monastery of St. Thomas (CDS II 9, No. 108, p. 86). In the nun miller survey of 1682 (by HB Kärtzer; Table 1), the Paußnitz is not shown as a river at all but as a wetland in the Probstei forest (Fig. 12). On the Öder-Zimmmermann map it is a rather short river and is not completely depicted. Therefore, it indicates that the Paußnitz River, compared to other water bodies, had a lesser significance as a discrete flowing water body. The specific fluvial–geomorphological structures from the geomorphological survey show, however, that the Paußnitz was a dynamic watercourse in the past. The first written mention dates back to 1349 as “fluvius [...] Pustenicz” (CDS II 9, No. 108, p. 86-87). The name is most probably derived from the Slavic word pusty for barren, wild (Eichler and Walther, 2010; Greule, 2014). On the mileage sheets, the toponyms Schwarze Lache and Schwarze Lagge (black puddle) can be found in the area of the Paußnitz River course, which indicates that the Paußnitz River did not constantly carry water every year but rather reflects a wetland with oxbow lakes or backflow channels with still water characteristics. This corresponds to the representation in the nun miller survey map, which rather shows a wetland than a discrete river course (Fig. 12). At the same time, there are strong indications from the geomorphological survey of an active, dynamic course of the Paußnitz River, which shows an active meandering behaviour (Fig. 4). It must have existed before the mileage sheets were mapped. On the 19th-century maps, it appears to be a canalized stream (Fig. 4). We assume that this river changed its dynamics over time and only had a fixed river channel in the 18th century. Overall, the significant phases of river modifications were before the 13th century regarding the hydropower and in the early 17th century regarding timber rafting (Fig. 11C). The use of the rivers to power the mills and the use of the floodplain forests to feeding cattle and supply wood were the drivers behind these major transformations. Regarding the river network, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, significant influence was exerted as flood protection measures and straightening actions at a high technical level completely changed the water network structure (Haase and Nuissl, 2007; Berkner, 2018). This, among other things, resulted in a decrease in the total water body length (Fig. 11B).

Figure 12Map of the nun miller HB Kärtzer 1682 (see Table 1), modified. The map depicts green spaces and traces the courses of the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers within the Elster–Pleiße floodplain. An inset map on the upper left shows the city of Leipzig.

5.5 River stabilization by anthropogenic measures

In addition to sedimentological constraints, direct anthropogenic measures on rivers can also play a role in the stabilization of rivers in the southern Leipzig area. The Leipzig floodplain has been used for a long time, and widespread human intervention is therefore to be suspected at least since the beginning of the Middle Ages, although there have been isolated finds in the floodplains around Leipzig since the Neolithic period (Denzer et al., 2015; Liebmann, 2023). Furthermore, Neolithic finds have been discovered scattered throughout the catchment areas of the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers (Tinapp et al., 2019; Miera et al., 2022). The use of the floodplain forest (e.g. as a timber source) can be dated back to medieval times (Lange, 1959; Rehm, 1996).

An example of river-related protective measures is the regulation of fish ponds along the Pleiße River close to the city. Measures of damming the Pleiße River close to the city and fish ponds with willows can be seen in sources from around 1500 (CDS II 9, No. 366, p. 363; CDS II 8, No. 481, p. 402). In 1475, fishers were granted the right to fish in the holes in the southwest of the city, which were left over after the removal of the brick earth and happened to carry water. This water was held permanently with the help of willows. In 1503, the monastery of St. Thomas argued against the city council of Leipzig that the willows planted in the wild waters (Pleiße) were washing away their meadows. Despite these findings, it is not clear to what extent riverbank protections have been installed along smaller rivers and outside the direct urban environment. Further research is needed here.

On the old maps, since the 17th century, rows of trees can be seen along the river (Fig. 12). It is likely that these trees are willows, as this genus can grow well in moist locations and can cope with standing water for an extended period of time. These willows can also be seen in most of the land surveys (e.g. mileage sheets) and sketches of the time (Fig. 3).

Written sources from the early modern period also show that willow plantations were used directly to increase bank stability. “In addition, the ditch on this side can be dug out only little, or not at all, because of the willows standing on our meadows; otherwise, the roots would be undermined and the bank might collapse” (own translation, freely translated, 1725; Leipzig municipal archive, 0008 (Ratsstube), II. Sekt. G/328a, Bd. 1, fol. 34v). Willows along the rivers stabilize the banks through their roots and thereby protect the banks from lateral erosion (van Splunder et al., 1994; Makaske, 2001; Horton et al., 2017). Furthermore, the historical practice of planting willows along riverbanks, as observed in old maps, served as a noteworthy economic utilization of these areas, which were not suitable for other land uses due to the wetland conditions (Burggraaff, 2021; Rotherham, 2022). This strategy allowed the harvest of willow wood, used for firewood and wicker works. These specific measures for stabilizing riverbanks have a long tradition and must be regarded as factors of stabilizing river courses.

By combining a high‐resolution LiDAR DTM survey with a diachronic analysis of old maps (16th–20th century), we reconstruct a clear shift in the Elster–Pleiße floodplain from a formerly dynamic one, with active meanders, to a largely stabilized channel network. The geomorphological survey within the floodplain (oxbows, ridge-and-swale point bars, etc.) documents extensive past lateral activity, especially in the interfluve between the Weiße Elster and Pleiße rivers where the Paußnitz and Batschke rivers are located. In contrast, present channel positions and the historical cartographic record show only minor shifts in bend position since at least the early 17th century, alongside a consistent decline in sinuosity.

Our research questions are addressed as follows: (i) The DTM‐based survey reveals that the rivers once exhibited pronounced mobility, with preserved levees and scroll bars indicating sustained meander migration before map coverage. (ii) The transition to relative channel stability was already in progress by the period covered by the Öder–Zimmermann map (late 16th to early 17th century) and was subsequently reinforced by 18th–20th century engineering, including timber rafting canalization of the Batschke River, mill races, channel straightening, and 20th-century flood protection basins. (iii) Stabilization reflects the combined effect of anthropogenic controls and sedimentological boundary conditions: progressive aggradation of cohesive overbank fines that increased bank strength and widespread bank vegetation (notably planted willows) that reduced erodibility.

These findings have direct relevance for river restoration and floodplain management. Historical channel patterns and preserved geomorphological features offer reference conditions and spatial guidance for reconnecting former anabranches. Overall, acknowledging the long anthropogenic trajectory of this floodplain is essential for realistic objectives that enhance ecological function while respecting entrenched legacies in topography, sediment, and infrastructure.

Data available on request from the corresponding author.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-74-355-2025-supplement.

JS: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, software, formal analysis, data curation, investigation, visualization, writing (original draft and review and editing). SL: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, investigation, writing (original draft and review and editing). FG: data curation, investigation. MHe: investigation, writing (review and editing). NL: data curation, writing (review and editing). JSF: funding acquisition, writing (review and editing). MH: funding acquisition, writing (review and editing).

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Floodplain architecture of fluvial anthropospheres”. It is not associated with a conference.

We thank the Amt für Stadtgrün und Gewässer for joint discussions about the recent water network in the study area. We also thank Martin Offermann and Iris Niessen for engaging discussions on the analysis of old maps and the human impacts on river stabilization and its archaeological implications. Johannes Schmidt wishes to express his personal gratitude to Kalluna Kiesow for her enduring and inspiring enthusiasm for observing the world. Furthermore, we would like to thank the German Research Foundation (DFG) for funding (SCHM 3801/1-1, HA 4496/1-1, SCHM 2992/1-1). We would also like to thank all members of the DFG SPP 2361 for exciting exchanges and discussions on the topic of the fluvial anthroposphere. The study is supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of Leipzig University. Finally, we thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback that improved the article.

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant nos. SCHM3801/1-1, HA 4496/1-1 and SCHM 2992/1-1).

This paper was edited by Olaf Bubenzer and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Andronov, S., Baum, D., and Hartmann, H. (Eds.): Der Elsterflossgraben: Geschichte und Gestalt eines technischen Denkmals, PRO LEIPZIG e.V, Leipzig, ISBN 978-3-936508-08-6, 2005. a, b

Arnhold, H.: Die Bedeutung der Elster-Pleisse-Aue für die Entwicklung der Stadt Leipzig, Wiss. Veröff. Dt. Inst. Länderkde N.F., 21/22, 395–421, 1964. a

Aster, F. L.: Sächsische Meilenblätter (Berliner Exemplar) – 19: Leipzig, https://geoviewer.sachsen.de/mapviewer/resources/apps/hika/index.html?lang=de (last access: 4 April 2025), 1802a. a

Aster, F. L.: Sächsische Meilenblätter (Berliner Exemplar) 27: Markkleeberg, Großdeuden, Gaschwitz, https://geoviewer.sachsen.de/mapviewer/resources/apps/hika/index.html?lang=de (last access: 4 April 2025), 1802b. a

Aster, F. L.: Sächsische Meilenblätter (Berliner Exemplar) – 18: Plagwitz, Leipzig-Schönau, Leipzig-Lindenau, https://geoviewer.sachsen.de/mapviewer/resources/apps/hika/index.html?lang=de (last access: 4 April 2025), 1806. a

Ballasus, H., Schneider, B., von Suchodoletz, H., Miera, J., Werban, U., Fütterer, P., Werther, L., Ettel, P., Veit, U., and Zielhofer, C.: Overbank silt-clay deposition and intensive Neolithic land use in a Central European catchment – Coupled or decoupled?, The Science of the total environment, 806, 150858, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150858, 2022. a, b

Beckenbach, E.: Geologische Interpretation des hochauflösenden digitalen Geländemodells von Baden-Württemberg, PHD-thesis, Institut für Planetologie Universität Stuttgart, Stuttgrat, https://doi.org/10.18419/opus-8846, 2016. a

Becker, B. and Schirmer, W.: Palaeoecological study on the Holocene valley development of the River Main, southern Germany, Boreas, 6, 303–321, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3885.1977.tb00296.x, 1977. a

Benito, G., Thorndycraft, V. R., Rico, M., Sánchez-Moya, Y., and Sopeña, A.: Palaeoflood and floodplain records from Spain: Evidence for long-term climate variability and environmental changes, Geomorphology, 101, 68–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2008.05.020, 2008. a

Berkner, A.: Der Leipziger Elsterstausee: Seine Geschichte vom Anfang bis zum Ende, Pro Leipzig, Leipzig, [1. auflage] Edn., ISBN 978-3-945027-30-1, 2018. a

Berkner, A.: Das Leipziger Neuseenland zwischen Bergbausanierung, Wasserwirtschaft und Regionalentwicklung, WASSERWIRTSCHAFT, 109, 14–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s35147-019-0039-1, 2019. a

Blaschke, K. (Ed.): Atlas zur Geschichte und Landeskunde von Sachsen. Beiheift zu den Karten, druckhaus köthen GmbH, Leipzig, 2002. a

Brandolini, F. and Carrer, F.: Terra, Silva et Paludes . Assessing the Role of Alluvial Geomorphology for Late-Holocene Settlement Strategies (Po Plain – N Italy) Through Point Pattern Analysis, Environmental Archaeology, 26, 511–525, https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1740866, 2021. a

Broothaerts, N., Verstraeten, G., Notebaert, B., Assendelft, R., Kasse, C., Bohncke, S., and Vandenberghe, J.: Sensitivity of floodplain geoecology to human impact: A Holocene perspective for the headwaters of the Dijle catchment, central Belgium, The Holocene, 23, 1403–1414, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683613489583, 2013. a

Brown, A. G.: Learning from the past: palaeohydrology and palaeoecology, Freshwater Biology, 47, 817–829, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00907.x, 2002. a

Brown, A. G., Carey, C., Erkens, G., Fuchs, M., Hoffmann, T., Macaire, J.-J., Moldenhauer, K.-M., and Des Walling, E.: From sedimentary records to sediment budgets: Multiple approaches to catchment sediment flux, Geomorphology, 108, 35–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2008.01.021, 2009. a

Brown, A. G., Lespez, L., Sear, D. A., Macaire, J.-J., Houben, P., Klimek, K., Brazier, R. E., van Oost, K., and Pears, B.: Natural vs anthropogenic streams in Europe: History, ecology and implications for restoration, river-rewilding and riverine ecosystem services, Earth-Science Reviews, 180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.02.001, 2018. a, b

Brown, A. G., Rhodes, E. J., Davis, S., Zhang, Y., Pears, B., Whitehouse, N. J., Bradley, C., Bennett, J., Schwenninger, J.-L., Firth, A., Firth, E., Hughes, P., and Des Walling: Late Quaternary evolution of a lowland anastomosing river system: Geological-topographic inheritance, non-uniformity and implications for biodiversity and management, Quaternary Science Reviews, 260, 106929, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.106929, 2021. a

Brunner, H.: Übergabe der sächsischen Meilenblätter an Preußen, Neues Archiv für sächsische Geschichte, 78, 251–254, https://doi.org/10.52411/nasg.Bd.78.2007.S.251-254, 2007. a

Buchty-Lemke, M. and Lehmkuhl, F.: Impact of abandoned water mills on Central European foothills to lowland rivers: a reach scale example from the Wurm River, Germany, Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 100, 221–239, https://doi.org/10.1080/04353676.2018.1425621, 2018. a, b

Büntgen, U., Brázdil, R., Heussner, K.-U., Hofmann, J., Kontic, R., Kyncl, T., Pfister, C., Chromá, K., and Tegel, W.: Combined dendro-documentary evidence of Central European hydroclimatic springtime extremes over the last millennium, Quaternary Science Reviews, 30, 3947–3959, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.10.010, 2011a. a

Büntgen, U., Tegel, W., Nicolussi, K., McCormick, M., Frank, D., Trouet, V., Kaplan, J. O., Herzig, F., Heussner, K.-U., Wanner, H., Luterbacher, J., and Esper, J.: 2500 years of European climate variability and human susceptibility, Science (New York, N.Y.), 331, 578–582, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197175, 2011b. a, b, c

Bünz, E.: Klöster und Stifte, in: Geschichte der Stadt Leipzig, edited by: Bünz, E. and John, U., 482–498, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig, ISBN 978-3-86583-801-8, 2015. a

Bünz, E. and John, U. (Eds.): Geschichte der Stadt Leipzig: Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart: Ausgabe in vier Bänden, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig, ISBN 978-3-86583-801-8, 2015. a

Burggraaff, P.: Kulturgeschichte der Kopfbäume am Unteren Niederrhein: Arbeitsstudie eines vom Landschaftsverband Rheinland (LVR) geförderten Projekts des Naturschutzzentrums im Kreis Kleve e.V., Vol. 44 of Arbeitsstudie, Selbstverlag der LVR-Abteilung Kulturlandschaftspflege, Köln, https://www.lvr.de/media/wwwlvrde/kultur/kulturlandschaft/aktuelles_3/publikationen_5/22_0114_Broschuere_Kulturgeschichte_der_Kopfbaeume_barr.pdf (last access: 28 November 2025), 2021. a

Candel, J. H. J., Kleinhans, M. G., Makaske, B., Hoek, W. Z., Quik, C., and Wallinga, J.: Late Holocene channel pattern change from laterally stable to meandering – a palaeohydrological reconstruction, Earth Surf. Dynam., 6, 723–741, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-6-723-2018, 2018. a, b, c

Cook, E. R., Seager, R., Kushnir, Y., Briffa, K. R., Büntgen, U., Frank, D., Krusic, P. J., Tegel, W., van der Schrier, G., Andreu-Hayles, L., Baillie, M., Baittinger, C., Bleicher, N., Bonde, N., Brown, D., Carrer, M., Cooper, R., Čufar, K., Dittmar, C., Esper, J., Griggs, C., Gunnarson, B., Günther, B., Gutierrez, E., Haneca, K., Helama, S., Herzig, F., Heussner, K.-U., Hofmann, J., Janda, P., Kontic, R., Köse, N., Kyncl, T., Levanič, T., Linderholm, H., Manning, S., Melvin, T. M., Miles, D., Neuwirth, B., Nicolussi, K., Nola, P., Panayotov, M., Popa, I., Rothe, A., Seftigen, K., Seim, A., Svarva, H., Svoboda, M., Thun, T., Timonen, M., Touchan, R., Trotsiuk, V., Trouet, V., Walder, F., Ważny, T., Wilson, R., and Zang, C.: Old World megadroughts and pluvials during the Common Era, Science advances, 1, e1500561, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500561, 2015. a, b

Cottin, M.: Siedlungsgeschichte der Leipziger Landes vom 10. bis zum 13. Jahrhundert, in: Geschichte der Stadt Leipzig, edited by: Bünz, E. and John, U., Vol. 1, 156–176, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig, ISBN 978-3-86583-801-8, 2015a. a

Cottin, M.: Stadt-Land-Beziehungen, in: Geschichte der Stadt Leipzig, edited by: Bünz, E. and John, U., Vol. 1, 686–714, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig, ISBN 978-3-86583-801-8, 2015b. a, b, c