the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Historical clay extraction from paleo-channel deposits of the late-glacial Bergstraßenneckar in the Upper Rhine Graben, southwestern Germany

Felix Henselowsky

Annette Kadereit

Manuel Herzog

Barbara Tuczek

Heinrich Thiemeyer

Olaf Bubenzer

Henselowsky, F., Kadereit, A., Herzog, M., Tuczek, B., Thiemeyer, H., Bubenzer, O., and Engel, M.: Historical clay extraction from paleo-channel deposits of the late-glacial Bergstraßenneckar in the Upper Rhine Graben, southwestern Germany, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 75, 33–47, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-75-33-2026, 2026.

Linear anomalies of vegetation vitality observed in satellite images motivated in-depth investigations of historical anthropogenic modification and exploitation of the paleo-floodplain of the late-glacial Bergstraßenneckar (BSN) in the Upper Rhine Graben near Mannheim (southwestern Germany). Stratigraphic investigations based on up to 1.7 m deep pits, sediment sampling, and laboratory analyses (grain size distribution; C, N, S; loss on ignition; X-ray fluorescence; morphoscopy of sand grains), as well as electrical resistivity tomography, reveal the presence of long parallel trenches cutting into the organic-rich and fine-grained natural strata which result from silting-up of the abandoned BSN channel during the Holocene. The linear features are interpreted as anthropogenic trenches and were later filled with sand. We identify an aeolian origin of the sand, which points to the use of sand, e.g., from the nearby Bettenberg dune of Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to late-glacial age. The samples for optically stimulated luminescence dating (OSL) from the fill of the trenches show a wide range of equivalent doses and insufficient bleaching as sand was filled in lumps during shoveling. This results in ages ranging from the LGM to 300 years, depending on the aliquot and age model. This wide range indicates incomplete bleaching and is in agreement with the manual filling process in historical times. Further corroboration is provided by data from the Hesse State Archive at Darmstadt through a license for clay mining and brick burning at the study site dated to 1865 CE, explicitly requiring immediate fill. Local-scale clay pits for mud-brick production have been known about in western Europe since Roman times. However, access to the resources in the BSN channels in 1865 CE was only possible after a significant fall in groundwater tables following the regulation campaign of the Rhine system starting in the first half of the 19th century, which, in a wider context, illustrates the extent to which large-scale anthropogenic changes in the fluvioscape have cascading effects down to the local scale.

Auffällige lineare Vegetationsanomalien auf Satellitenbildern innerhalb des natürlich verlandeten Paläomäanders des spätglazialen Bergstraßenneckars (BSN) im Oberrheingraben bei Mannheim gaben Anlass zur Untersuchung möglicher anthropogener Eingriffe. Stratigraphische Untersuchungen auf Basis von bis zu 1,7 m tiefen Gruben, Sedimentproben und Laboranalysen (Korngrößenverteilung; C, N, S; Glühverlust; Röntgenfluoreszenz; morphoskopische Sandanalyse) sowie einer elektrischen Widerstandstomographie zeigen das Vorhandensein langer paralleler Gräben, die in die organikreichen und feinkörnigen natürlichen Sedimente des holozänen Verlandungsbereichs der BSN-Rinne eingeschnitten sind. Die linearen Strukturen im Satellitenbild spiegeln somit Unterschiede in Feuchtigkeitsgehalt und Wasserspeicherkapazität zwischen den feinkörnigen Auenablagerungen und dem Mittelsand, der die Gräben füllt, wider. Proben für optisch stimulierte Lumineszenzdatierung (OSL) der sandigen Grabenverfüllung weisen eine große Bandbreite an Äquivalenzdosen und eine unzureichende Rückstellung des Lumineszenz-Signals auf, da der Sand mutmaßlich schaufelweise verfüllt wurde. Dies führt zu berechneten Altern, die je nach Aliquot und Altersmodell zwischen dem letztglazialen Maximum und 300 Jahren vor heute liegen. Aus dem Hessischen Staatsarchiv Darmstadt liegt für das untersuchte Flurstück eine Konzession für Tonabbau und Ziegelherstellung aus dem Jahr 1865 vor. Die Genehmigung verlangt die sofortige Wiederverfüllung der Abbaugruben, wofür das Material in der nahe gelegenen Bettenberg-Düne zu vermuten ist. Die historische Datierung des Tonabbaus ist im Einklang mit den OSL-Daten aus der Verfüllung. Lokale Tongruben zur Ziegelherstellung wurden in Westeuropa seit der Römerzeit betrieben. Der Tonabbau im ehemaligen BSN-Mäander im Jahr 1865 war jedoch erst durch den im Zuge der Regulierungskampagne des Rheinsystems seit der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts erheblich gesunkenen Grundwasserspiegel möglich. Dieses Beispiel zeigt deutlich die lokalen Auswirkungen großräumiger anthropogener Eingriffe in die Flusslandschaft.

- Article

(6635 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3490 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

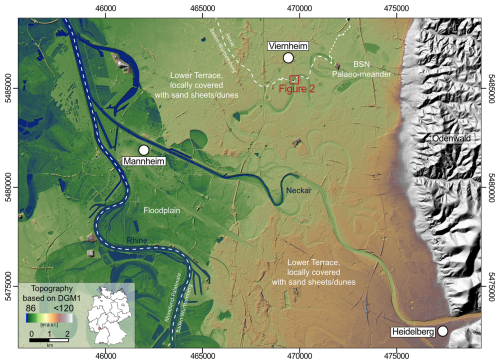

The term Bergstraßenneckar (BSN) refers to a now inactive course of the lower reaches of the Neckar River in the Upper Rhine Graben (URG) in southwestern Germany. Today, the Neckar flows directly from Heidelberg (MQ =161.4 m3 s−1, MHQ =1172.3 m3 s−1; LUBW, 2025a) to its confluence with the Rhine River near Mannheim after cutting the southern Odenwald mountains and entering the Upper Rhine Graben. However, from the late-glacial period (approx. 14 500 BP) until the onset of the Holocene (Dambeck, 2005), it ran northward across the Neckar alluvial fan and parallel to the western margin of the Odenwald mountains (Bergstraße). It merged with the Rhine River approximately 50 km further north at Trebur (Mone, 1826; Mangold, 1892; Dambeck 2005; Dambeck and Thiemeyer, 2002; Beckenbach, 2016; Engel et al., 2022; Appel et al. 2024). Its paleo-meander channels can still be identified morphologically and in satellite imagery, and they still determine roads, settlement patterns, and cadastral boundaries in many cases (Beckenbach, 2016). Some sections of the BSN were reactivated by smaller tributaries flowing from the Bergstraße into the URG and were used as waterways during historical times (Eckoldt, 1985; Appel et al., 2024).

After the naturally induced major shift of the BSN fluvial system at the late-glacial–Holocene transition, anthropogenic river regulations at the Neckar and Rhine represent the next major change to the hydrological system in the URG, leading to shortened river courses, river incision, and lowering of the groundwater table (Dister et al., 1990; Fuchs, 2025). Thus, the area is a typical palimpsest of natural and anthropogenic activity forming a restructured floodplain as a “fluvial anthroposphere” in the sense of Werther et al. (2021).

Here, we present geomorphological and historical evidence for a so far unreported anthropogenic exploitation of clay deposits within the BSN paleo-river channel, which is connected to previous research on the southern part of the BSN (Engel et al., 2022). We investigate an enigmatic morphometric and pedological anomaly in the floodplain between Mannheim and Heidelberg at the border between the states of Baden-Württemberg and Hesse to address the following goals: (1) to reconstruct the evolution of the paleo-meander, (2) to determine the origin and age of the linear vegetation pattern, and (3) to assess the effects of supra-regional hydrological changes on the fluvial architecture and land use in the paleo-floodplain. Ultimately, the research question being explored relates to the extent to which the silted-up river meanders of the BSN are not only a landscape archive but also a cultural archive. Our interdisciplinary dataset includes the high-resolution digital elevation model (DGM1), multi-temporal satellite images, and stratigraphic analysis using geophysics (electrical resistivity tomography, ERT) and sediment samples taken from excavation pits. Fieldwork data are supported by pedo-sedimentary laboratory analyses, optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating, and historical documents and maps from archives of the state of Hesse (Hessisches Landesarchiv, Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt).

The study site Rindlache, situated on land parcel (Flurstück) 153, cadastral section (Flur) 57 of the town of Viernheim (Hesse), represents one of the most prominent paleo-meander channel sections of the southern BSN, with a well-preserved channel morphology (outer bank, slip-off slope) and a half-meander path length of 800–900 m. The local field name refers to standing water conditions (“Lache”) due to both a high groundwater table and limited infiltration capacity of the clay-rich substrate in the paleo-channel and to the use for cattle grazing (“Rind”) in historical times (Engel et al., 2022). The site is located north of the Neckar alluvial fan close to the towns of Heddesheim and Viernheim, ca. 15 km northeast of Heidelberg, in the eastern part of the URG (Fig. 1) (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1988; Fuchs, 2025). The Odenwald represents the eastern graben shoulder and consists of a Palaeozoic basement covered mainly by Triassic Bunter Sandstone (Nickel and Fettel, 1979; Przyrowski and Schäfer, 2015). Thus, the main erosional products transported by the Neckar River are red sandstone and a variety of limestones, which make up the majority of the Neckar catchment (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1979, 1988; Löscher, 2007).

Following the climate classification of Köppen-Geiger, the study area has a Cfb climate, denoted as warm temperate and fully humid with warm summers (Kottek et al., 2006). The mean annual temperature is 10.2 °C with an annual precipitation of 722 mm (reference period: 1961–1990; LUBW, 2025b).

At Rindlache, the BSN incised up to 4 m deep and approx. 150 m wide into the late Pleistocene deposits of the Lower Terrace of the River Rhine (Fig. 1), leaving high-energy fluvial deposits with varying ratios of sand and gravel (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1979; Engel et al., 2022). Previous research on the late-glacial to Holocene evolution of the Rindlache paleo-meander shows a sequence of high-energy fluvial bedload (sand, gravel) to low-energy fluvio-limnic suspended load (clay-rich organoclastic and calcareous mud) and peat formation in the center of the paleo-channel, overlain by silt- and fine-sand-dominated alluvium and colluvium, forming the modern agricultural soil (Roth, 2020; Engel et al., 2022).

On top of the Lower Terrace east of the Rhine, sand dunes – typically of the parabolic type – occur frequently. The closest dune to our field site is located at a distance of only approx. 200 m (Bettenberg). These dunes and cover sands within the northern URG are generally of Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to late-glacial age, with some anthropogenically induced re-activation during the Holocene (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1979; Löscher and Haag, 1989; Dambeck, 2005; Holzhauer et al., 2017; Pflanz et al., 2022).

The study applies a multi-methodological and interdisciplinary approach combining data from remote sensing, as well as geophysical, sedimentological, and geochronological investigations, and the evaluation of historical documents.

3.1 Satellite imagery and digital elevation model

Multi-temporal satellite images embedded in GoogleEarth Pro were used to determine changes in the vegetation pattern across a time span of almost 25 years (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). Morphometric investigations were supported by the digital elevation model DGM1 of the Federal State of Baden-Württemberg, established from 2000 to 2005 (LUBW, 2024). All GIS-based investigations were carried out using QGIS software v. 3.34.8.

3.2 Geophysical prospection

Geophysical prospection was based on 2-D ERT using a GeoTom MK1E100 device with Schlumberger and Dipol-Dipol configurations, with each configuration being measured with 100 electrodes and 0.5 m spacing, as described in Kneisel (2003). The ERT line from NNW to SSE runs perpendicular to the investigated linear anomaly. ERT data were post-processed by the calculation of standard inversions without filtering using Res2Dinv software. Erroneous data points, e.g., due to electrodes disconnecting during the measurement, were deleted from the raw dataset prior to data modeling.

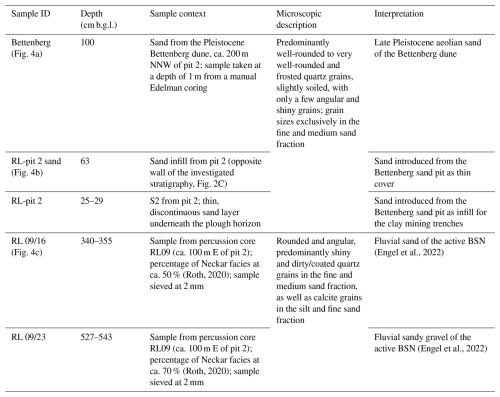

Figure 2(A) Satellite image of the BSN paleo-meander and the Bettenberg dune from 8 July 2018 (imagery © 2009 GeoBasis-DE/BKG, map data © 2025 Google), with marked positions of transect ERT-19 and hand-dug pits 1 and 2 and with contour lines derived from DGM1 (LUBW, 2024); (B) sketch of parallel sand infillings, natural stratigraphic contexts, and associated sampling pits; (C) field impression from pits 1 and 2; (D) profile ERT-19 (see Fig. 2A for location).

3.3 Sediment soil pits and sedimentary analyses

Two pits were dug down to a depth of 170 cm on plot (Flur) 57 (“Rindlache”), parcel (Flurstück) 153. Pit 1 in the southwestern part of the land parcel and pit 2 in the northeastern part of the land parcel (Figs. 2A, C and S5) both cut the anomalies and allow for a three-dimensional study of the stratigraphies, which was described in the field according to Ad-hoc AG Boden (2005) and the Munsell Soil Color Charts (Munsell Color Company, 2000). Samples were taken from both stratigraphic sections.

Samples taken at pit 2 were dried, carefully pestled by hand, and dry-sieved (2 mm). Grain size distributions of the <2 mm fraction were measured using a laser particle sizer (Fritsch Analysette 22 NeXT Nano) at the Laboratory for Geomorphology and Geoecology, Institute of Geography, Heidelberg University. Samples were pre-treated with H2O2 (30 %) to dissolve organic matter and Na4P2O7 (55.7 g L−1) to dissolve soil aggregates. Univariate statistical measures were calculated using GRADISTAT v9.1 (Blott and Pye, 2001). Organic matter (LOI550) and carbonate content (LOI950) were determined by loss-on-ignition (LOI) following a slightly modified protocol from Heiri et al. (2001). Samples of 3–5 g were combusted in a muffle furnace, first at 550 °C for 4 h and then at 950 °C for 4 h. C, N, and S were simultaneously measured using high-temperature combustion (Elementar VarioMax organic elemental analyzer) on aliquots homogenized using a mixer mill (Retsch MM 301). X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy analysis was carried out using a Thermo Scientific Niton XL3t handheld device inside a radiation-proof measurement chamber. For XRF analysis, dried, homogenized aliquots were pressed into pellets with a perfectly smooth surface to guarantee a high reproducibility of the measurements. Several NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) soil standards were measured together with the samples for data quality control. After centered log ratio transformation following Bertrand et al. (2024), the XRF data were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) using Past software v4.16 (Hammer et al., 2001) to support the facies model.

To supplement facies interpretation and identify the source area of the sand found in the pits, particle shape, grain size, and mineral composition were qualitatively studied under a Keyence VHX-2000 digital microscope with reflected light for five samples. Morphoscopic interpretation was mainly based on Liang and Yang (2023).

3.4 OSL dating

From the sand unit creating the linear anomalies, six samples in total were taken for OSL dating in lightproof steel cylinders (samples HDS-1818 to HDS-1820 from pit 2; samples HDS-1821 to HDS-1823 from pit 1; Table S2). As experiments on quartz and feldspar minerals showed that quartz bleaches significantly faster than feldspar (Godfrey-Smith et al., 1988), we extracted quartz coarse grains (125–212 µm) from the OSL sediment samples for equivalent-dose (De) determination. Sample preparation occurred under subdued red light in the Heidelberg Luminescence Laboratory following standard procedures (Fig. S13). For the potentially poorly bleached samples, the analysis of single grains or subsamples (aliquots) with only a few grains would be preferential to identify the well-bleached grains in a population of variably bleached grains. However, the relatively dim luminescence signal of the samples only allowed us to investigate “small aliquots” (∼ 102 grains each; ø 4 mm; grains strewn on aluminum cups, ø 10 mm, and fixed with silicon oil). The measurements were performed on an automated luminescence reader, model TL/OSL DA15 (upgraded to DA20; Bøtter-Jensen et al., 2000; DTU Physics, 2021), applying a blue-light-stimulated luminescence (BLSL) single-aliquot regeneration (SAR) protocol (Murray and Wintle, 2000) (Fig. S14) and detecting the UV quartz emission around 340 nm through a set of glass filters (3× U340, Hoya, 2.5 mm each). BLSL stimulation occurred for 40 s at 125 °C (400 data channels; 0.1 s per data channel). Potential feldspar contamination was tested in a final cycle of the SAR protocol by IR stimulation prior to BLSL (OSL IR depletion ratio) (Duller, 2003). De determination was performed with the Luminescence Analyst software, v4.31.9 (Duller, 2015). De's were calculated for the integrals 0–0.1 and 0–0.4 s, using 30.1–40 s for late-light subtraction. Central doses and minimum doses (Galbraith et al., 1999) for central age model (CAM) and minimum age model (MAM) age determination were calculated using the functions of Burow (2023a, b) with the R package “Luminescence” (Kreutzer et al., 2012). Radionuclide determination was done using the μ dose system (Tudyka et al., 2018; Kolb et al., 2022). The cosmic dose rate was assessed according to Prescott and Hutton (1988) and Hutton and Prescott (1992) with a function of the R package Luminescence (Burow, 2024). For effective dose rate calculation, the ratio of a sample's wet weight to dry weight (Δ) was assumed to be 1.05±0.05. CAM and MAM ages (Galbraith et al., 1999) were calculated based on data in Table S13. In addition, for graphical representation, apparent OSL ages of the individual aliquots, derived by dividing the De's of the individual aliquots by a sample's mean dose rate, were plotted in ascending order of OSL ages (Fig. 5). All methodological details are provided in Supplement Sect. S3.

3.5 Historical archives

Information on the historical land use of the study site was acquired from historical archives of the state of Hesse (Hessisches Landesarchiv, Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt). We searched digital copies (Digitalisate; available at Arcinsys Hessen; https://arcinsys.hessen.de, last access: 9 January 2026) of files on land use in the area of Viernheim (G 15 Heppenheim V 598) which include official permits; directories of names of owners of land parcels (Namensverzeichnis zum topographischen Güterverzeichnis von Viernheim; H 23 No. 3491); and, for the geographical allocation and matching of the historical plans with modern land parcel numbers, an atlas of the land parcels (Parzellenatlas; P 4 No. 2737).

4.1 Satellite imagery and digital elevation model

Noticeable changes in vegetation vitality based on multi-temporal GoogleEarth imagery are visible during different seasons on the following dates: 1 June 2000, 19 April 2015, 8 July 2018, and 30 June 2019 (Figs. 2A and S1). They all show a linear pattern of pale-green and yellowish colors versus fully green colors running from SSW to NNE. The linear pattern covers an area of approximately 100 m ×50 m. While stripes in the eastern part are less pronounced, the western part exhibits incomplete and shorter stripes.

The maximum width of pale-green stripes (up to 3.5 m) occurs in the central part. The DEM shows that the surface of the linear pattern (“upper-level surface”) lies ca. 0.4 m above the present-day surface of the neighboring paleo-channel (“lower-level surface”).

4.2 ERT

The transect ERT-19 reaches down to ca. 7 m below ground level (b.g.l.). For the Schlumberger configuration (Fig. 2D), the base between 7–4 m b.g.l. consists of low resistivity values between 20 and 75 Ωm with a horizontal layering. Between 4–2 m b.g.l., the lowest resistivities are in the range of 10–20 Ωm, also reflecting horizontal layers. The only area with higher values at this depth is at 9–10 m horizontal distance, where resistivity reaches values of 200–300 Ωm. The uppermost 2 m are characterized by alternating resistivity values varying between sections of 10–30 and 300–600 Ωm. Overall, there are nine circular high-resistivity anomalies from NNW to SSE, coinciding with the individual stripes. Between 38 and 49.5 m horizontal distance, sections of high resistivity are less pronounced. The Dipol-Dipol configuration shows a similar pattern, with less pronounced horizontal layering for the lower units (Fig. S2).

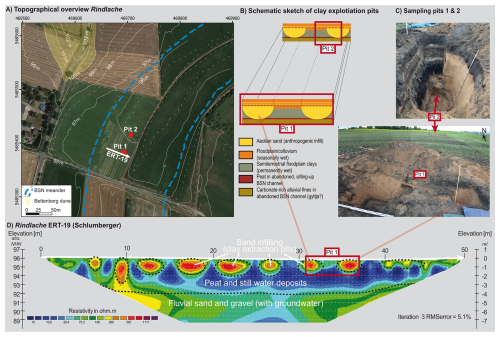

Figure 3Stratigraphy of the western wall of pit 2 and the sand infill with data on mean grain size, sorting, grain size distribution, LOI550, LOI950, C, N, S, Ca/Ti, and Fe/Mn, as well as the vertical distribution of the facies model (see also Fig. 6). Pedological horizons follow the updated German soil systematics in Ad-hoc AG Boden (2024) (b.g.l. denotes below ground level, cl denotes clay, vfsi denotes very fine silt, fsi denotes fine silt, msi denotes medium silt, csi denotes coarse silt, vcsi denotes very coarse silt, vfs denotes very fine sand, fs denotes fine sand, ms denotes medium sand, and cs denotes coarse sand).

4.3 Sedimentology and stratigraphy

The sampling pits (Fig. 2C) cut the linear anomaly. Thus, the profiles show disturbed (pit 1 and eastern profile of pit 2) and undisturbed (western profile of pit 1) stratigraphic sections. The general stratigraphic pattern is very similar in both pits; here, we describe the undisturbed part based on the western profile of pit 2 (Fig. 3). The stratified, light-yellowish-brown base unit S10 (170–140 cm b.g.l.) consists of carbonate-rich (LOI950 >20 %), moderately to poorly sorted sandy silt. Iron oxidation occurs along root casts, whereas organic content is moderate (LOI550 ∼ 12 %). S10 represents a feF ° Gor horizon according to the updated German classification of pedological horizons in Ad-hoc AG Boden (2024) (see Table S1 for further explanations of pedological horizons). It is overlain by a black peat (S9 [fnH], 140–104 cm b.g.l.), void of carbonate but very high in organic matter (LOI550 ∼ 70 %), S (0.28 %), and N (2.55 %), whereas the Fe/Mn ratio is low. The overlying black unit S8 (eMm, 104–98 cm b.g.l.) consists of an organic-rich (LOI550 ∼ 24 %), moderately sorted clayey silt, high in S (0.23 %) and Fe/Mn but low in carbonate (LOI950 ∼ 3.8 %). It is overlain by poorly sorted black to dark-gray fine sandy silt (S7 [eMm], 98–61 cm b.g.l.) with similar carbonate (LOI950 ∼ 3.5 %) and lower organic (LOI550 ∼ 6.7 %) contents, whereas the Fe/Mn ratio is high. It contains white fine roots and some gastropod shell fragments. Unit S6 (61–49 cm b.g.l.) is a poorly sorted, carbonate-rich (LOI950 ∼ 20 %) loam, showing a mottled pattern resulting from iron oxides and carbonate precipitation, especially around root casts (Fig. S8). S6 (Gor – eMcm) has the highest number of gastropod shells and shell fragments out of the entire stratigraphy. Unit S5 (Gor – eMm, 49–40 cm b.g.l.) consists of yellowish dark-gray, poorly sorted sandy loam with a gritty texture, iron stains, and abundant gastropod shell fragments. The carbonate content is relatively high (LOI950 ∼ 11 %), and the organic content is also increased (LOI550 ∼ 15 %). Unit S4 (Dj, ∼ 40 cm b.g.l.; up to 3 cm thick) is a yellowish-brown, well-sorted thin and discontinuous medium sand with small dark-brown mud clasts and very sharp boundaries. Organic (LOI550 ∼ 1.6 %) and carbonate (LOI950 ∼ 1 %) contents, as well as S (0.01 %) and N (0.06 %) values, are relatively low. It is overlain by unit S3 (Dj, 40–29 cm b.g.l.), a very dark-gray, poorly sorted loamy sand with abundant iron stains, root penetration, and gastropod shell fragments (plus one entirely preserved shell). S2 (Dj, 29–25 cm b.g.l.) resembles the medium sand of S4, including the discontinuous nature, very sharp undulating boundaries, and fine mud clasts (Fig. S7). The top layer (S1 [Dj], 25–0 cm b.g.l.) consists of poorly sorted, very dark-gray silty loam with abundant roots, few angular to subrounded gravel components, a brick fragment, and a few fine gastropod shell fragments.

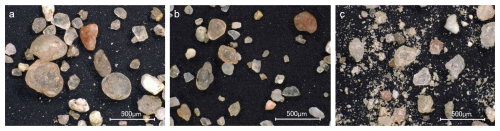

Figure 4Microscope images (100× magnification) of (a) sand from the Pleistocene Bettenberg dune, approximately 200 m NNW of pit 2; (b) the sand infill from pit 2, eastern profile (opposite wall of the investigated stratigraphy, Fig. 2C); and, for comparison, (c) fossil fluvial sand of the active BSN (RL09 in Engel et al., 2022), containing 50 % clasts from the Neckar catchment. A more detailed facies description can be found in Table 1.

At the opposite wall, the eastern profile of pit 2, a massive, unstratified unit of medium sand cuts into the stratigraphic pattern down to unit S9 (Figs. 2C, 4b). Underneath the sand deposits, Unit S10 consists of the same carbonate-rich sandy silt as in the undisturbed section of pit 2. The grain size distribution, sorting, and geochemistry of the unstratified sand strongly overlaps with those of S2; it furthermore contains mud clasts and drapes of mud (Figs. S3, S4). It is only covered by S1, with some grayish humic material incorporated into the upper part of the infill (Figs. 2C and S5).

The northern profile of pit 1, ca. 50 m south of pit 2, shows the same disturbed stratigraphy as the eastern profile of pit 2, starting with unit S10 at the base, followed by a massive, unstratified unit of medium sand and covered by unit S1. In pit 1, the sand infill also contains some centimeter- to decimeter-scale mud clasts and mud lenses. Locally, an up to 3 cm thick layer of whitish, powdery carbonate was observed at a depth of around 35 cm b.g.l (Fig. S5). Furthermore, a hollow brick (Hohlziegel) was observed in the uppermost part of the light-colored sand infill (Fig. S6), identified as a survey point of the land consolidation campaign Viernheim DF 459 from the 1970–1980s (personal communication, Dieter Hogen, Amt für Bodenmanagement, 23 September 2020).

Microscopic investigations of sand grain characteristics show great similarities with the samples from the Bettenberg dune. Both the massive sand unit of the linear anomalies and the discontinuous sand layer S2 in pit 2 show well-rounded to very well-rounded and frosted quartz grains, slightly soiled, with only a few angular and shiny grains. Grain sizes are exclusively in the fine and medium sand fractions (Fig. 4a, b, Table 1). In contrast, samples from the active BSN channel (samples RL09/16 and RL09/23 from Engel et al., 2022) reveal rounded and angular, predominantly shiny and dirty or coated quartz grains in the fine and medium sand fractions, as well as calcite grains in the silt and fine sand fractions (Fig. 4c).

4.4 OSL dating

In total, 236 aliquots of the six OSL samples from the two pits gave acceptable results. OSL ages for the six different samples calculated following the CAM range from approximately 2.1 ka (HDS-1821) to approximately 6.5 ka (HDS-1823), while OSL ages calculated following the MAM range from approximately 0.6.–0.7 ka (HDS-1822) to approximately 3 ka (HDS-1820). The results are based on 20 aliquots (HDS-1818, HDS-1920) to 113 aliquots (HDS-1822) per sample passing the acceptance criteria for the De determination (Sect. S3). The apparent ages of the individual aliquots of all six samples are given in ascending order of OSL ages in Fig. 5A. The sandy material used for the infilling of the trenches may have been of pre-Holocene age, possibly up to LGM age. Aliquots pointing to material handling within the last 1000 years are given in Fig. 5B.

4.5 Historical archives

A file on brickyards and brick manufactures (Akte zu Ziegeleien und Backsteinbrennereien in Viernheim; G 15 Heppenheim V 598, 1875) lists several brickworks (licensed to the names of Kühner, Bläß, Samstag, and Martin); however, these are located outside the study site (former cadastral sections VII and I of Martin). A license for the brickworks site of Peter Minnig from 1865 CE (digital version, image 88) does not mention the land parcel studied here. However, attached to it is a plan with land parcels adjacent to the border between Hesse and Baden-Württemberg (formerly Großherzogthum Baden) on the Hessian side (digital version, image 90). Land parcel no. 2 is marked as a field of the mayor Michael Keller, and no. 3 (Klafter 1473) is marked as a field of P. Minnig. Therefore, in the directory of the topographical list of land parcels (Namensverzeichnis zum topographischen Güterverzeichnis von Viernheim; H 23 No. 3491) we searched for land parcels of Michael Keller and P. Minnig, which are located in the same cadastral section and carry similar plot numbers. These criteria are fulfilled by plot no. 34 (M. Keller) and 33 and 41 (P. Minnig) in the cadastral section XXI. The position of the former cadastral section XXI was retrieved from the plot atlas (Parzellenatlas; P 4 No. 2737). The respective land parcels are found in section A, image 21 (Abteilung A, Bild 21) (Figs. S9, S10). The former land parcel no. 33 (owner P. Minnig; see reference above) covers the linear anomalies of the present-day land parcel 153. In addition to the plan, the conditions under which a license for clay mining was granted are detailed:

“Field no. 1 is the plot on which the brickworks site shall be established. The plot is situated 1/2 hour south of Viernheim, and it is 450 feet wide and 360 feet long. The substrate for the brick manufacture will be excavated in the center of the plot and the pits will be refilled immediately. From time to time the bricks are put together approximately in the center of the plot and burned with stone coal. Viernheim 1st June 1865” (for the original wording in German, see Sect. S2).

5.1 Stratigraphy and sedimentation pattern

5.1.1 Facies model for Pit 2

Five different facies types exposed in pit 2 (I–V) are identified by the PCA based on XRF data (Fig. 6):

- i.

The bottom unit S10 of almost white, carbonate-rich substrate may correspond to the calcareous gyttja forming at the bottom of the gradually silting-up meander channels of the abandoned BSN during the Preboreal and Boreal periods, as identified by Bos et al. (2008) in other parts of the BSN.

- ii.

The overlying peat bog (S9) reflects the silting-up process of the abandoned BSN meander, dating generally from the Boreal to the Subboreal period (Dambeck, 2005; Bos et al., 2008; Appel et al., 2024) and up to ca. 6500 cal yr BP at the study site (Engel et al., 2022). The young age at the Rindlache possibly implies a hiatus in deposition also known from other BSN paleo-channel sections (Dambeck and Bos, 2002) or the erosion of older peat.

- iii.

In the following, a distal floodplain sequence started to form, fed by flooding events of the active Neckar course nearby (S7, S8). This sequence starts with organic-rich black clays, likely a reflection of soil erosion through an initial Neolithic forest clearing (Kalis et al., 2003; Bos et al., 2008). Around the southern BSN, the Late Neolithic Michelsberg (ca. 4400–3500 BCE; Lang, 1996) and/or the end Neolithic Corded Ware ceramic (ca. 2900–2350 BCE; König, 2015) cultures may have triggered increased soil erosion and the formation of the black clays (Engel et al., 2022). The abundant gastropod shells reflect an open, amphibic floodplain environment (Löscher and Haag, 1989), supported by high Fe/Mn ratios indicating (temporarily) anaerobic conditions (Davies et al., 2015).

- iv.

Overlying is a colluvium with a basal horizon of secondary carbonate precipitation at the capillary fringe supported by a higher pore volume (S6). Hydromorphic features, as well as calcareous precipitations, likely formed within the former zone of a fluctuating groundwater table (locally denoted as “Rheinweiß”), showing that the site was once waterlogged due to a higher groundwater table (“Lache”) (Dambeck, 2005). The secondary carbonate close to the top of pit 1 (Fig. S5) represents anthropogenic soil amelioration during the refilling of the trenches. It should be noted that the sand infill of the trenches does not show such hydromorphic features. S5 represents the natural Holocene soil developed in the post-silting-up colluvium with overlying sediments from the adjacent western terrace slope and the nearby Bettenberg dune. The age of this colluvium is unclear.

- v.

The fifth facies type is represented by anthropogenically modified aeolian sands, appearing as thin, discontinuous layers (S2, S4 between the colluvial material, and the sand infill). This interpretation is based on the good sorting and the morphoscopic analysis, showing the similarity to sand of the adjacent Bettenberg dune, which is of late-glacial to Allerød age (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1979; Löscher and Haag, 1989), and a lack of carbonate typically associated with the fluvial sands of the BSN (Table 1). Mud clasts of variable size (Figs. S3 and S4) indicate unintentional mixing with the surrounding topsoil during the anthropogenic infilling of the trenches. Thus, the adjacent Bettenberg dune, which, indeed, has a historical sand quarry located at its southern end (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1979), seems to be the most likely sand source.

The loamy alluvial to colluvial deposits and topsoil (I Dj) are reflected by low resistivity values of the ERT profile (bluish colors, 10–20 Ωm), which, below approximately 3 m b.g.l., are replaced by high resistivity values (greenish colors, 20–75 Ωm) representing the sandy and gravelly material of the active BSN channel which is incised into the Lower Rhine Terrace deposits (Engel et al., 2022). Here, the current groundwater level is reached, which causes still relatively low resistivity values for these coarse-grained sediments.

This sequence, completed by underlying gravelly sands of the late-glacial active BSN channel and laminated fine sands and silts representing the cut-off to completely disconnected stages (Engel et al., 2022), compares well with model sequences of paleo-channel infilling both in the northern URG (Dambeck, 2005; Dambeck and Thiemeyer, 2002; Bos et al., 2008; Appel et al., 2024) and elsewhere in central and western Europe (e.g., Kasse et al., 2005; Wójcicki, 2006; Tolksdorf et al., 2013). The stacked units of gyttja, peat, and clay indicate a fully disconnected still-water setting where changes in sedimentation represent a function of late-glacial to mid-Holocene environmental changes and, regarding the black clay, human impact, interspersed with rare overbank sedimentation during major floods (Wójcicki, 2006; Toonen et al., 2012).

5.2 Chronology

5.2.1 Termini post quem

Age indicators pre-dating the trench filling include 14C data of the peat below the anthropogenic extraction (Engel et al., 2022); the clasts of mature Holocene soil in the sandy infill (Figs. S3 and S4); and, most importantly, the timing of the Rhine River regulations. Both the peat and subsequent soil formation date into the mid-Holocene, with the youngest peat-based 14C dating from Rindlache at 6539–6402 cal yr BP (Engel et al., 2022).

The river regulations and straightening initiated by Johann Gottfried Tulla in the 19th century (period of the hydraulic constructions: 1817–1882 CE) led to incision of the Rhine River of up to approx. 10 m and lowering of the groundwater table across the URG. Before these regulations and more recent intensified exploitation of drinking and irrigation water (see Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1979; Dister et al., 1990; Fuchs, 2025), the morphological depressions of the BSN paleo-channels hosted swamps and seasonal shallow-standing waterbodies, exemplified by archeological traces of Roman bridges or corduroy roads (Greyer et al., 1977; Eckoldt, 1985; Wagner, 1990; Wirth, 2011). Anthropogenic usage of these areas was restricted to cattle pasture and the construction of wells (Mone, 1826).

Based on the lack of hydromorphic features in the sand infill, the general groundwater level must have been lowered to a depth of >1.5 m at the time of clay mining, which only occurred after the onset of the regulation measures. In contrast, the Rheinweiß in the undisturbed stratigraphy (S6) reflects the relict higher groundwater table before the regulation measures (Fig. S8). Thus, only the lower groundwater at Rindlache as a remote effect of the large-scale river regulations in the URG made the clay extraction possible. This also illustrates the extent to which the massive anthropogenic changes in the fluvial landscape in the Upper Rhine Graben had cascading effects of human impact at the local scale.

Whether the groundwater table had already fallen below the bottom of the trenches at the time of clay mining cannot be definitively answered. The bridge walls of undisturbed limno-fluvial deposits between the trenches may be interpreted as protection measures against inflowing water, which otherwise could have drowned the extraction sites in between. Narrow trenches can be protected from groundwater influx more easily, at least temporarily, than larger clay extraction pits.

5.2.2 Termini ante quem

Age indicators post-dating the trench infilling include the hollow brick pushed into the sand infill and a lack of any trenching-related activities documented in the German states soil appraisal (“Reichsbodenschätzung”). The hollow brick was installed at a depth of approximately 40 cm b.g.l. to carry survey equipment for the regional land consolidation process of the 1970–1980s (personal communication, Thomas Heinz, Amt für Bodenmanagement, 28 September 2020). The Reichsbodenschätzung does not mention any soil amelioration or land improvement for land parcel 153 since the 1930s (personal communication, Stefan Schmauch, tax authority, Bensheim branch, 2020). During the Nazi regime, works by the Reich Labor Service (“Reichsarbeitsdienst”), who had, e.g., drained the Hessische Ried north of Viernheim, are not documented for land parcel 153 and therefore seem to post-date the trenches.

5.2.3 Interpretation of the OSL data

All termini post and ante quem are in good agreement with both the age of the license of the brickwork site from 1865 CE (Sect. 5.2.4) and the OSL ages. The broad range of apparent ages of the infill, most likely originating from the Bettenberg dune, starts in late-glacial times, with a few exceptions conforming to the time of the LGM (Fig. 5). Both the LGM and the late glacial are periods of intense aeolian activity in the URG, with the late glacial being the time of most likely preservation of dunes (Löscher and Haag, 1989; Dambeck, 2005; Holzhauer et al., 2017; Pflanz et al., 2022). The strong scatter of the ages indicates that the quartz grains were insufficiently bleached in historical times and that the latent luminescence signal was not fully reset during the transfer from the Bettenberg quarry into the clay-mining trenches. The youngest apparent ages point to ca. 300–400 a as a maximum age for the material transfer. The resetting of the latent (late-glacial) luminescence signal of the sand grains was apparently not sufficient to indicate the true age of 158 a. This finding is not surprising, given the shoveling of the sand lumps. As we assume that the trenches were refilled with sand within a short period of time of a few days, weeks, or months, the different samples may be regarded to represent the same event with respect to OSL dating and resetting of the latent luminescence signal, respectively.

5.3 Historical sources of clay exploitation

The anthropogenic excavations and sand infilling inferred from the historical sources (Sect. 4.5) reach the depth of the black clay (S8) or peat (S9), respectively. This observation suggests that the reason for the trenching was the mining of the clay-rich units S6 to S8. The immediately underlying peat uncovered during clay mining may have been used as an energy source as peat still used to be a relevant burning material in the northern URG at that time (Mone, 1826; Tasche, 1858).

The trench walls from pit 2 are slightly sloped or sometimes stepped-sloped towards the interior of the trench, and they were most likely dug by hand with a spade or a similar tool. Excavators or other equipment were introduced for peat mining only after 1865 CE (Günther, 2020). Not all trenches run continuously from end to end. Several of the outer trenches on the northwestern side run parallel to the other trenches but represent shorter and disconnected trench sections in a line. This observation supports the interpretation that the trenches were dug manually, perhaps with different people starting at different sections along a predefined line and not always excavating until the next dugout was reached. It also suggests that the trenching and the immediate refilling of the excavated trenches were done one after another.

Activities of clay mining are known of in the area from at least the Middle Ages. Approximately 850 m to the northwest of land parcel 153, a former clay pit of approximately 100 m ×150 m areal size and 3 m depth is still visible as a rectangular depression in the present-day landscape. The site name, “Egelsee”, refers to a clay pit once drowned by groundwater and populated by leeches, as documented for 1482 CE. Along with the brickwork site of 1865 CE, other former brickwork sites are mentioned for Viernheim, less than 2 km away from Rindlache, for the 19th century. Licenses for clay manufactures in the study area are documented for the periods 1827–1828, 1837, 1864–1873, and 1898–1905.

The general use of river clays for mud-brick production, however, dates back to PPNB (Pre-Pottery Neolithic B) contexts ca. 9500 years ago in the southwestern Fertile Crescent (sun-dried brick) and the early 5th millennium by the Indus civilization (baked bricks) (Stordeur and Khawam, 2007; Van Beek and Van Beek, 2008; Gibling, 2018). In western Europe, baked mud bricks were introduced during the time of the Roman Empire (Van Beek and Van Beek, 2008; Lehouck, 2019), with traces of systematic clay mining in Holocene floodplains both in the Roman Heartland (Scalenghe et al., 2015; Vanzani et al., 2025) and also north of the Alps, with examples in Germany (Obrocki et al., 2020), Switzerland (Maggetti and Galetti, 1993), or Britain (Claughton, 2016). Mud bricks as building material disappeared after the Romans left, mostly until the 12th century CE (Lehouck, 2019), when clays of the Holocene floodplain were used again for mud-brick production throughout western Europe (Van Dinter, 2013; Claughton, 2016; Goemaere et al., 2019). The demand for local clay sources must have been high since then; the present study shows that, still in the 19th century, these resources were exploited at a local scale as soon as they were discovered or became accessible – e.g., through human-induced lowering of the groundwater table, as in the present case.

Overall, our multi-methodological approach allows us (1) to reveal the different phases of the silting-up for reconstructing the evolution of the BSN meander from late glacial–early Holocene to recent times, (2) to identify the origin of the linear anomalies as remnants of clay mining in the paleo-floodplain; and (3) to show how large-scale river regulations and associated groundwater level fall permitted access to exploitable resources in the paleo-floodplain of the BSN.

The undisturbed profile of pit 2 within the paleo-channel of the BSN reveals distinct phases for the silting-up of the BSN and is in good agreement with previous research done in the area (Engel et al., 2022). However, it adds important previously unknown phases of historic to (sub-)recent human activity. Clay mining at Rindlache is a good example of how the anthropogenic environmental impact on large spatial scales trickles down to the local scale by facilitating access to previously inaccessible resources in historical times, e.g., due to high groundwater level. Observations of similar striped vegetation anomalies in multi-temporal satellite images in comparable landscape contexts of the Hessisches Ried and historic sources for brickworks e.g., near Lorsch and Biblis, potentially indicate similar clay exploitation techniques. So far, detailed field investigations were almost missing, or the hypothesis of clay extraction was only based on results from a sediment core (Appel et al., 2024). Our insights into the silted-up river channels as a source of raw materials, here for the production of bricks, thus represents an important further contribution to the consideration of a fully comprehensive fluvial anthroposphere, where past human activity is the greatest change in today's landscape palimpsest.

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the text, as well as in two supplement files.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-75-33-2026-supplement.

FH, AK, and ME conceived and designed the study. The fieldwork and laboratory analyses were carried out by FH, AK, MH, HT, OB, and ME. The research into historical sources was done by BT. A first draft of the paper was written by FH, AK, and ME. All of the authors commented on and approved the paper.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a guest member of the editorial board of E&G Quaternary Science Journal for the special issue “Floodplain architecture of fluvial anthropospheres”. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Floodplain architecture of fluvial anthropospheres”. It is not associated with a conference.

We thank Dr. Peter Müller (Mannheim-Straßenheim) for the permission to conduct fieldwork on his property. On 14 October 2020, our inspections of the profile walls were kindly supported by Bernhard Keil (Oberfinanzdirektion Frankfurt), Heike Gundlach (Finanzamt Darmstadt), and Stefan Schmauch (Amt für Bodenmanagement Heppenheim; Finanzämter Bensheim und Michelstadt). Digging of the trenches was kindly supported by Lea Bell, Bastian Ditschmann, Florian Frychel, Marc Heptig, Nico Kohler, Philipp Kupke, Sonja Lissak, Helena Oberbauer, Sandy Placzek, Matteo Reiß, Alissa Ritter, Dominik Ruck, and Thomas Scharffenberger as part of a field course of the undergraduate program in Geography at Heidelberg University, summer term 2020. The sedimentological analyses were kindly supported by Jannik Berte, Alexander Hecht, Sylvia Pscheidl and Marvin Weiler as part of a laboratory course of the undergraduate program in Geography at Heidelberg University, winter term 2020–2021. OSL laboratory work was done with the help of Jutta Asmuth. The sedimentary laboratory work was kindly supported by Nicola Manke. Brigitta Kersting kindly helped to decipher the current script. The comments and suggestions of two anonymous reviewers helped to improve this paper; their work and effort are greatly acknowledged.

This open-access publication was funded by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

This paper was edited by Christopher Lüthgens and Frank Lehmkuhl and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ad-hoc AG Boden: Bodenkundliche Kartieranleitung, 5th ed., Schweizerbart, Hannover, 2005.

Ad-hoc AG Boden: Bodenkundliche Kartieranleitung, 6th ed., two volumes, Schweizerbart, Hannover, 2024.

Appel, E., Becker, T., Wilken, D., Fischer, P., Willershäuser, T., Obrocki, L., Schäfer, H., Scholz, M., Bubenzer, O., Mächtle, B., and Vött, A.: The Holocene evolution of the fluvial system of the southern Hessische Ried (Upper Rhine Graben, Germany) and its role for the use of the river Landgraben as a waterway during Roman times, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 73, 179–202, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-73-179-2024, 2024.

Barsch, D. and Mäusbacher, R.: Erläuterungen zur Geomorphologischen Karte 1:25 000 der Bundesrepublik Deutschland – GMK 25 Blatt 3, 6417 Mannheim-Nordost, in: GMK Schwerpunktprogramm, Geomorphologische Detailkartierung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, edited by: Barsch, D., Fränzle, O., Leser, H., Liedtke, H., and Stäblein, G., Berlin, 1–56, 1979.

Barsch, D. and Mäusbacher, R.: Zur fluvialen Dynamik beim Aufbau des Neckarschwemmfächers, Berlin. Geogr. Abh. , 47, 119–128, https://doi.org/10.23689/fidgeo-3194, 1988.

Beckenbach, E.: Geologische Interpretation des hochauflösenden digitalen Geländemodells von Baden-Württemberg, PhD thesis, University of Stuttgart, Germany, https://doi.org/10.18419/opus-8846, 2016.

Bertrand, S., Tjallingii, R., Kylander, M. E., Wilhelm, B., Roberts, S. J., Arnaud, F., Brown, E., and Bindler, R.: Inorganic geochemistry of lake sediments: A review of analytical techniques and guidelines for data interpretation, Earth Sci. Rev., 249, 104639, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104639, 2024.

Blott, S. J. and Pye, K.: GRADISTAT: a grain size distribution and statistics package for the analysis of unconsolidated sediments, Earth Surf. Processes Landforms, 26, 1237–1248, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.261, 2001.

Bos, J. A. A., Dambeck, R., Kalis, A. J., Schweizer, A., and Thiemeyer, H.: Palaeoenvironmental changes and vegetation history of the northern Upper Rhine Graben (southwestern Germany) since the Lateglacial, Neth. J. Geosci., 87, 67–90, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600024057, 2008.

Bøtter-Jensen, L., Bulur, E., Duller, G. A. T., and Murray, A. S.: Advances in luminescence instrument systems, Radiat. Meas., 32, 523–528, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1350-4487(00)00039-1, 2000.

Burow, C.: calc_CentralDose(): Apply the central age model (CAM) after Galbraith et al. (1999) to a given De distribution. Function version 1.4.1, in: Luminescence: Comprehensive Luminescence Dating Data Analysis. R package version 0.9.21, edited by: Kreutzer, S., Burow, C., Dietze, M., Fuchs, M. C., Schmidt, C., Fischer, M., Friedrich, J., Mercier, N., Philippe, A., Riedesel, S., Autzen, M., Mittelstrass, D., Gray, H. J., Galharret, J., Colombo, M., Steinbuch, L., and de Boer, A., CRAN, https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.Luminescence, 2023a.

Burow, C.: calc_MinDose(): Apply the (un-)logged minimum age model (MAM) after Galbraith et al. (1999) to a given De distribution. Function version 0.4.4, in: Luminescence: Comprehensive Luminescence Dating Data Analysis. R package version 0.9.21, edited by: Kreutzer, S., Burow, C., Dietze, M., Fuchs, M. C., Schmidt, C., Fischer, M., Friedrich, J., Mercier, N., Philippe, A., Riedesel, S., Autzen, M., Mittelstrass, D., Gray, H. J., Galharret, J., Colombo, M., Steinbuch, L., and de Boer, A., CRAN, https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.Luminescence, 2023b.

Burow, C.: calc_CosmicDoseRate(): Calculate the cosmic dose rate. Function version 0.5.2, in: Luminescence: Comprehensive Luminescence Dating Data Analysis. R package version 0.9.21, edited by: Kreutzer, S., Burow, C., Dietze, M., Fuchs, M. C., Schmidt, C., Fischer, M., Friedrich, J., Mercier, N., Philippe, A., Riedesel, S., Autzen, M., Mittelstrass, D., Gray, H. J., Galharret, J., Colombo, M., Steinbuch, L., and de Boer, A., CRAN, https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.Luminescence, 2024.

Claughton, P.: Clay, in: The Archaeology of Mining and Quarrying in England – A Research Framework for the Archaeology of the Extractive Industries in England. Resource Assessment and Research Agenda, edited by: Newman, P., National Association of Mining History Organisations, Derbyshire, 127–141, 2016.

Dambeck, R.: Beiträge zur spät- und postglazialen Fluss- und Landschaftsgeschichte im nördlichen Oberrheingraben, PhD thesis, University of Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2005.

Dambeck, R. and Thiemeyer, H.: Fluvial history of the northern Upper Rhine River (southwestern Germany) during the Lateglacial and Holocene times, Quaternary Int., 93–94, 53–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-6182(02)00006-X, 2002

Dambeck, R. and Bos, J. A. A.: Lateglacial and Early Holocene landscape evolution of the northern Upper Rhine River valley, south-western Germany, Z. Geomorph. Suppl., 128, 101–127, 2002.

Davies, S. J., Lamb, H. F., and Roberts, S. J.: Micro-XRF core scanning in palaeolimnology: recent developments, in: Micro-XRF Studies of Sediment Cores, edited by: Croudace, I. W. and Rothwell, R. G., Springer, Dordrecht, 189–226, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9849-5_7, 2015.

Dister, E., Gomer, D., Obrdlik, P., Petermann, P., and Schneider, E.: Water management and ecological perspectives of the upper Rhine's floodplains, Regul. River., 5, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/rrr.3450050102, 1990.

DTU Physics: The Risø TL/OSL reader, https://physics.dtu.dk/-/media/institutter/fysik/nutech/produkter-og-services/radiation_measurement_instruments/tl_osl_reader/manuals/reader.pdf, (last access: 26 February 2025), 2021.

Duller, G. A. T.: Distinguishing quartz and feldspar in single grain luminescence measurements, Radiat. Meas., 37, 161–165, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1350-4487(02)00170-1, 2003.

Duller, G. A. T.: The Analyst software package for luminescence data: overview and recent improvements, Ancient TL, 33, 35–42, 2015.

Eckoldt, M.: Schiffahrt auf kleinen Flüssen. T. 2, Gewässer im Bereich des “Odenwaldneckars” im ersten Jahrtausend n. Chr. Dt. Schiffahrtsarch., 8, 101–116, 1985

Engel, M., Henselowsky, F., Roth, F., Kadereit, A., Herzog, M., Hecht, S., Lindauer, S., Bubenzer, O., and Schukraft, G.: Fluvial activity of the late-glacial to Holocene “Bergstraßenneckar” in the Upper Rhine Graben near Heidelberg, Germany – first results, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 71, 213–226, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-71-213-2022, 2022.

Fuchs, M.: The Upper Rhine Graben: A diverse landscape shaped by endogenic and exogenic processes, in: Landscapes and Landforms of Germany, edited by: Lehmkuhl, F., Böse, M., and Krautblatter, M., Springer, Cham, 287–299, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-77876-6_16, 2025.

Galbraith, R. F., Roberts, R. G., Laslett, G. M., Yoshida, H., and Olley, J. M.: Optical dating of single grains of quartz from Jinmium rock shelter, northern Australia. Part I: experimental design and statistical models, Archaeometry, 41, 339–364, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.1999.tb00987.x, 1999.

Gibling, M. R.: River systems and the Anthropocene: A Late Pleistocene and Holocene timeline for human influence, Quaternary, 1, 21, https://doi.org/10.3390/quat1030021, 2018.

Godfrey-Smith, D. I., Huntley, D. J., and Chen, W.-H.: Optical dating studies of quartz and feldspar sediment extracts, Quat. Sci. Rev., 7, 373–380, https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-3791(88)90032-7, 1988.

Goemaere, E., Sosnowska, P., Golitko, M., Goovaerts, T., and Leduc, T.: Archaeometric and archaeological characterization of the fired clay brick production in the Brussels Capital Region between the XIV and the third quarter of the XVIII centuries (Belgium), ArcheoSciences, 43, 107–132, https://doi.org/10.4000/archeosciences.6429, 2019.

Greyer, W., Kandt, K., Kokes, I., and Schuler, H.: Die Römische Sumpfbrücke bei Bickenbach (Kreis Darmstadt), Saalburg-Jahrb., 34, 42–77, 1977.

Günther, J.: Torf als (nachwachsender) Rohstoff?, TELMA Beih. Ber. Dt. Ges. Moor- u. Torfk., 6, 369–379, 2020.

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T., and Ryan, P.D.: PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis, Palaeontol. Electron., 4, 2001.

Heiri, O., Lotter, A. F., and Lemcke, G.: Loss on ignition as a method for estimating organic and carbonate content in sediments: reproducibility and comparability of results, J. Paleolimnol., 25, 101–110, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008119611481, 2001.

Holzhauer, I., Kadereit, A., Schukraft, G., Kromer, B., and Bubenzer, O.: Spatially heterogeneous relief changes, soil formation and floodplain aggradation under human impact – geomorphological results from the Upper Rhine Graben (SW Germany), Z. Geomorph., 61, 121–158, https://doi.org/10.1127/zfg_suppl/2017/0357, 2017.

Hutton, J. T. and Prescott, J. R.: Field and laboratory measurements of low-level thorium, uranium and potassium, Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instr. D, 20, 367–370, https://doi.org/10.1016/1359-0189(92)90066-5, 1992.

Kalis, A. J., Merkt, J., and Wunderlich, J.: Environmental changes during the Holocene climatic optimum in central Europe – human impact and natural causes, Quat. Sci. Rev., 22, 33–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(02)00181-6, 2003.

Kasse, C., Hoek, W. Z., Bohncke, S. J. P., Konert, M., Weijers, J. W. H., Cassee, M. L., and Van Der Zee, R. M.: Late Glacial fluvial response of the Niers-Rhine (western Germany) to climate and vegetation change, J. Quaternary Sci., 20, 377–394, https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.923, 2005.

Kneisel, C.: Electrical resistivity tomography as a tool for geomorphological investigations – some case studies, Z. Geomorph. Suppl., 132, 37–49, 2003.

Kolb, T., Tudyka, K., Kadereit, A., Lomax, J., Poręba, G., Zander, A., Zipf, L., and Fuchs, M.: The μDose system: determination of environmental dose rates by combined alpha and beta counting – performance tests and practical experiences, Geochronology, 4, 1–31, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-4-1-2022, 2022.

König, P.: Eine vorgeschichtliche und frühmittelalterliche Siedlung von Heddesheim, Rhein-Neckar-Kreis, Fundber. Baden-Württemb., 35, 141–204, https://doi.org/10.11588/fbbw.2015.0.44523, 2015.

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B., and Rubel, F.: World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated, Meteorol. Z., 15, 259–263, https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130, 2006.

Kreutzer, S., Schmidt, C., Fuchs, M. C., Dietze, M., Fischer, M., and Fuchs, M.: Introducing an R package for luminescence dating analysis, Ancient TL, 30, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.26034/la.atl.2012.457, 2012.

Lang, A.: Die Infrarot-Stimulierte-Lumineszenz als Datierungsmethode für holozäne Lössderivate. Ein Beitrag zur Chronometrie kolluvialer, alluvialer und limnischer Sedimente in Südwestdeutschland, Heidelb. Geogr. Arb., 103, 1–137, 1996.

Lehouck, A.: The very beginning of brick architecture north of the Alps: the case of the Low Countries in the question of the Cistercian origin, in: L'industrie cistercienne (XIIe–XXIe siècle), edited by: Baudin, A., Benoit, P., Rouillard, J., and Rouzeau, B., Somogy Éditions d'Art, Paris, 41–56, 2019.

Liang, P. and Yang, X.: Grain shape evolution of sand-sized sediments during transport from mountains to dune fields, J. Geophys. Res. Earth, 128, e2022JF006930, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JF006930, 2023.

Löscher, M.: Die quartären Ablagerungen auf der Mannheimer Gemarkung, in: Mannheim vor der Stadtgründung. Teil 1, Band 1, edited by: Probst, H., Friedrich Pustet Verlag, Regensburg, 28–47, 2007.

Löscher, M. and Haag, T.: Zum Alter der Dünen im nördlichen Oberrheingraben bei Heidelberg und zur Genese ihrer Parabraunerden, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 39, 98–108, https://doi.org/10.3285/eg.39.1.10, 1989.

LUBW (Landesanstalt für Umwelt Baden-Württemberg): Digitales Geländemodell 1 Meter (DGM1), Object ID: 271f9e5b-6f12-4fc9-b692-cb7828e8c170, https://rips-metadaten.lubw.de/startseite (last access: 28 February 2025), 2024

LUBW (Landesanstalt für Umwelt Baden-Württemberg): Abfluss-BW – regionalisierte Abfluss-Kennwerte Baden-Württemberg, https://udo.lubw.baden-wuerttemberg.de/projekte/ (last access: 28 Febrary 2025), 2025a.

LUBW (Landesanstalt für Umwelt Baden-Württemberg): Klima der Vergangenheit, https://www.klimaatlas-bw.de/ (last access: 16 June 2025), 2025b.

Maggetti, M. and Galetti, G.: Die Baukeramik von Augusta Raurica – eine mineralogisch-chemisch-technische Untersuchung, Jahresber. Augst Kaiseraugst, 14, 199–225, 1993.

Mangold, A.: Die alten Neckarbetten in der Rheinebene, Abh. Großherzogl. Hess. Geol. Landesanst. Darmstadt, 2, 75–114, 1892.

Mone, F. J.: Ueber den alten Flußlauf im Oberrheintal, Badisch. Arch. z. Vaterlandsk. in allseit. Hinsicht, 1, 1–47, 1826.

Munsell Color Company: Munsell Soil Color Chart, New Windsor, 2000.

Murray, A. S. and Wintle, A. G.: The single aliquot regenerative dose protocol: potential for improvements in reliability, Radiat. Meas., 37, 377–381, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1350-4487(03)00053-2, 2000.

Nickel, E. and Fettel, M.: Odenwald – Vorderer Odenwald zwischen Darmstadt und Heidelberg, Sammlung Geologischer Führer Vol. 65, Bornträger, Stuttgart, 1979.

Obrocki, L., Becker, T., Mückenberger, K., Finkler, C., Fischer, P., Willershäuser, T., and Vött, A.: Landscape reconstruction and major flood events of the River Main (Hesse, Germany) in the environs of the Roman fort at Großkrotzenburg, Quaternary Int., 538, 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.08.009, 2020.

Pflanz, D., Kunz, A., Hornung, J., and Hinderer, M.: New insights into the age of aeolian sand deposition in the northern Upper Rhine Graben (Germany), Quaternary Int., 625, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.03.019, 2022.

Prescott, J. R. and Hutton, J. T.: Cosmic ray and gamma ray dosimetry for TL and ESR, Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instr. D, 14, 223–227, https://doi.org/10.1016/1359-0189(88)90069-6, 1988.

Przyrowski, R. and Schäfer, A.: Quaternary fluvial basin of northern Upper Rhine Graben, Z. Dt. Ges. Geowiss., 166, 71–98, https://doi.org/10.1127/1860-1804/2014/0080, 2015.

Roth, F.: Lithofazielle Differenzierung zur Aktivität und Verlandung ehemaliger Flussschleifen im Oberrheingraben – ein Beitrag zur Landschaftsgeschichte des südlichen Bergstraßenneckars, MSc thesis, Heidelberg University, 2020.

Scalenghe, R., Barello, F., Saiano, F., Ferrara, E., Fontaine, C., Caner, L., Olivetti, E., Boni, I., and Petit, S.: Material sources of the Roman brick-making industry in the I and II century A.D. from Regio IX, Regio XI and Alpes Cottiae, Quaternary Int., 357, 189–206, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2014.11.026, 2015.

Stordeur, D. and Khawam, R.: Les crânes surmodelés de Tell Aswad (PPNB, Syrie), Premier regard sur l'ensemble, premières réflexions, Syria, 87, 5–32, https://doi.org/10.4000/syria.321, 2007.

Tasche, H.: Kurzer Ueberblick über das Berg-, Hütten- und Salinen-Wesen im Grossherzogthum Hessen, G. Jonghaus, 1858.

Tolksdorf, J. F., Turner, F., Kaiser, K., Eckmeier, E., Stahlschmidt, M., Housley, R. A., Breest, K., and Veil, S.: Multiproxy analyses of stratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of the late Palaeolithic Grabow floodplain site, northern Germany, Geoarchaeology, 28, 50–65, https://doi.org/10.1002/gea.21429, 2013.

Toonen, W. H. J., Kleinhans, M. G., and Cohen, K. M.: Sedimentary architecture of abandoned channel fills, Earth Surf. Processes Landforms, 37, 459–472, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3189, 2012.

Tudyka, K., Miłosz, S., Adamiec, G., Bluszcz, A., Poręba, G., Paszkowski, Ł., and Kolarczyk, A.: μDose: A compact system for environmental radioactivity and dose rate measurement, Radiat. Meas., 118, 8–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radmeas.2018.07.016, 2018.

Van Beek, G. W. and Van Beek, O.: Glorious Mud! Ancient and Contemporary Earthen Design and Construction in North Africa, Western Europe, the Near East, and South Asia, Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, Washington, 2008.

Van Dinter, M.: The Roman Limes in the Netherlands: how a delta landscape determined the location of the military structures, Neth. J. Geosci., 92, 11–32, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600000251, 2013.

Vanzani, F., Fontana, A., Vinci, G., and Ventura, P.: The legacy of the Roman pottery production in the alluvial landscape in Italy: traces of relict clay pits and their ancient environmental impact, Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci., 17, 91, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02202-w, 2025.

Wagner, P. (Ed.): Die Holzbrücken bei Riedstadt-Goddelau, Kreis Groß-Gerau, Mater. Vor- und Frühgesch. Hessen, 5, 1–180, 1990.

Werther, L., Mehler, N., Schenk, G. J., and Zielhofer, C.: On the way to the Fluvial Anthroposphere–Current limitations and perspectives of multidisciplinary research, Water, 13, 2188, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13162188, 2021.

Wirth, K.: Ein Bohlenweg oder eine Sumpfbrücke aus römischer Zeit in Mannheim-Straßenheim, in: Archäologie der Brücken, Vorgeschichte, Antike, Mittelalter, Neuzeit, edited by: Pflederer, T. and Sommer, C., Friedrich Pustet Verlag, Regensburg, 102–105, 2011.

Wójcicki, K. J.: The oxbow sedimentary subenvironment: its value in palaeogeographical studies as illustrated by selected fluvial systems in the Upper Odra catchment, southern Poland, Holocene, 16, 589–603, https://doi.org/10.1191/0959683606hl953rp, 2006.