the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Nomes of Lower Egypt in the early Fifth Dynasty

Mohamed Ismail Khaled

Khaled, M. I.: Nomes of Lower Egypt in the early Fifth Dynasty, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 70, 19–27, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-70-19-2021, 2021.

Having control over the landscape played an important

role in the geography and economy of Egypt from the predynastic period

onwards. Especially from the beginning of the Old Kingdom, we have evidence

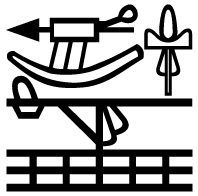

that kings created new places (funerary domains) called ![]() (centers) and

(centers) and

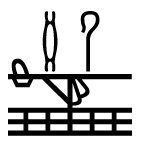

![]() (Ezbah) for the equipment of the building projects of the royal tomb and

the funerary cult of the king, as well as to ensure the eternal life of both

kings and individuals. Kings used these localities in order to do so, and they

oftentimes expanded the border of an existing nome and created new

establishments. Consequently, these establishments were united or divided

into new nomes. The paper discusses the geography of Lower Egypt and the

associated royal domains in the early Fifth Dynasty based on the new

discoveries from the causeway of Sahura at Abusir.

(Ezbah) for the equipment of the building projects of the royal tomb and

the funerary cult of the king, as well as to ensure the eternal life of both

kings and individuals. Kings used these localities in order to do so, and they

oftentimes expanded the border of an existing nome and created new

establishments. Consequently, these establishments were united or divided

into new nomes. The paper discusses the geography of Lower Egypt and the

associated royal domains in the early Fifth Dynasty based on the new

discoveries from the causeway of Sahura at Abusir.

Die geographische Unterteilung des Landes als Voraussetzung des Zugriff auf die Ressourcen des Landes spielte für die Wirtschaft Ägyptens und königliche Bauprojekte seit der prädynastischen Zeit eine wichtige Rolle. Um die landwirtschaftliche Nutzung des Landes auszuweiten und diesen Zugriff gleichzeitig zu sichern, begründeten die ägyptischen Könige Wirtschaftsanlagen (Grabdomänen) an schon bestehenden oder neu geschaffenen Siedlungen. Da sich der größte Teil der agrarisch nutzbaren Fläche im Delta befand, wurde im Laufe der Zeit auch das bestehende Gausystem dieses Gebietes mehrfach verändert. Das Papier erörtert die Geographie des Deltas in der frühen fünften Dynastie auf der Grundlage neuer Entdeckungen vom Aufweg des Pyramidenbezirkes des Sahure in Abusir (Abstract was translated by Eva Lange-Athinodorou.).

- Article

(19733 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The term nome is a territorial division in ancient Egypt; it comes from the ancient Greek word νoμóς, nomós. The term was used when the Greek language was common in Egypt, and this made the Greek historian adapt the term nome to identify the large lists of depictions of nomes with its divisions that are depicted in the late Greco-Roman temples. They usually take the shape of personified male or female figures, and they sometimes carry offerings; above their head is the sign of the nome that they represent, which is depicted on a standard.

In 1907–1908, Ludwig Borchardt carried out the principal exploration of the pyramid complex of Sahura, the second king of the Fifth Dynasty (2490–2475 BCE). Here, he discovered a large number of decorated wall reliefs which until today are considered the most complete example of a decorative program of a royal pyramid complex from the Old Kingdom. His publication still remains the most important source of information about the monument (Borchardt, 1910, 1913).

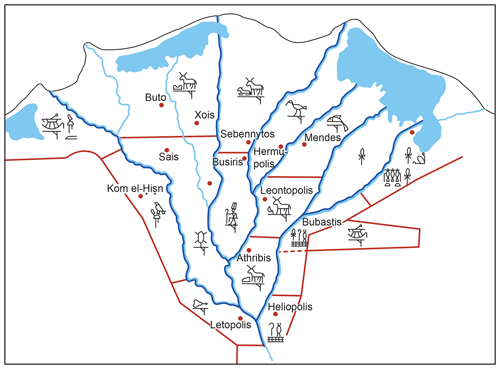

Figure 1The map of the delta showing the distribution of nomes during the Fifth Dynasty based on the work of Helck (1974), redrawn by Svenja Dirksen based on Helck (1974).

The decoration of the south wall of the southern portico of the side entrance to the king's pyramid temple shows different nomes from Lower Egypt in the form of a procession of the personifications of nomes and funerary domains of Sahura. Reflecting the physical geography of Egypt, the scene is divided symmetrically into a southern and a northern section. Unfortunately, only fragments depicting female personifications (most probably from Upper Egypt) were found by Borchardt (1913, 45–46, 106–109, plate 28).

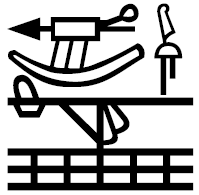

On the opposite north wall of the side entrance, the personifications of

Lower Egypt are depicted (Borchardt, 1913, 46, 109–111, plate 31). The scene shows two male and one female bearer of the nomes. The males

wear a long wig, necklace and false beard tied to the long wig by means of

straps. They also wear a short kilt. Their right hand holds a ![]() scepter,

while the loosely hanging left hand carries an

scepter,

while the loosely hanging left hand carries an ![]() sign. On a fragment

published by Borchardt (1913, 42, 105, plate 26), the symbol of the

first nome can be seen on the head of the male figure; a complete relief

depicting the 10th and 11th nomes of Lower Egypt was also

found by Borchardt (1913, 41, 105, plate 31). The female nome

personification wears a long wig with a lappet falling over her left

shoulder, which hangs down to the top of her long tight-fitting dress held

up by shoulder straps that expose her right breast. She wears a broad collar

consisting of several layers of beads and a tight choker necklace,

bracelets and anklets. Her right hand holds a

sign. On a fragment

published by Borchardt (1913, 42, 105, plate 26), the symbol of the

first nome can be seen on the head of the male figure; a complete relief

depicting the 10th and 11th nomes of Lower Egypt was also

found by Borchardt (1913, 41, 105, plate 31). The female nome

personification wears a long wig with a lappet falling over her left

shoulder, which hangs down to the top of her long tight-fitting dress held

up by shoulder straps that expose her right breast. She wears a broad collar

consisting of several layers of beads and a tight choker necklace,

bracelets and anklets. Her right hand holds a ![]() scepter, while the

loosely hanging left hand carries an

scepter, while the

loosely hanging left hand carries an ![]() sign. On the head of the female

figure is the symbol of the 16th nome of Lower Egypt. Two female

bearers of the

sign. On the head of the female

figure is the symbol of the 16th nome of Lower Egypt. Two female

bearers of the ![]() type, representing the centers that the king created in

each Egyptian nome, follow each of these figures.

type, representing the centers that the king created in

each Egyptian nome, follow each of these figures.

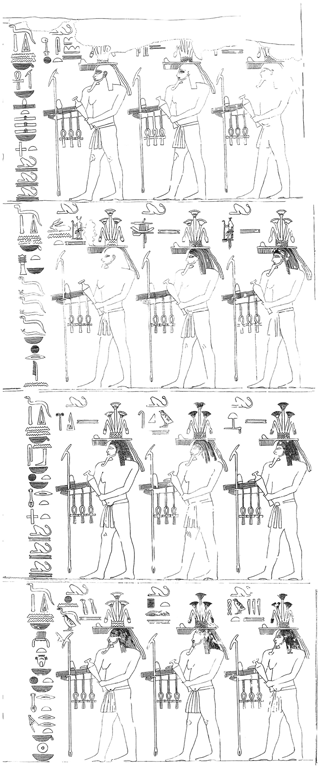

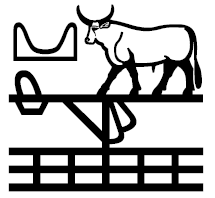

The recent excavation by the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) along the

upper part of the north wall of Sahura's causeway revealed the most complete

example of an Old Kingdom procession of funerary domains. The domains are

represented as both the ![]() and

and ![]() types. However, the majority are of

the

types. However, the majority are of

the ![]() type, and there are only six figures of the

type, and there are only six figures of the ![]() type. In addition

to the domains, the 10th nome and western part of the seventh nome of Lower Egypt are represented (Khaled, 2008, 101, 131–132). The procession

of the funerary domains of Sahura's causeway ends with an additional

section which shows a group of fecundity figures in four registers with

each register containing three figures. This list represents the northern

borders (subdivision) of the nomes depicted in the procession, representing

what is called the pehou (

type. In addition

to the domains, the 10th nome and western part of the seventh nome of Lower Egypt are represented (Khaled, 2008, 101, 131–132). The procession

of the funerary domains of Sahura's causeway ends with an additional

section which shows a group of fecundity figures in four registers with

each register containing three figures. This list represents the northern

borders (subdivision) of the nomes depicted in the procession, representing

what is called the pehou (![]() ) list, i.e., a list of the names of the

backwaters of each nome (Khaled, 2018, 235–42).

) list, i.e., a list of the names of the

backwaters of each nome (Khaled, 2018, 235–42).

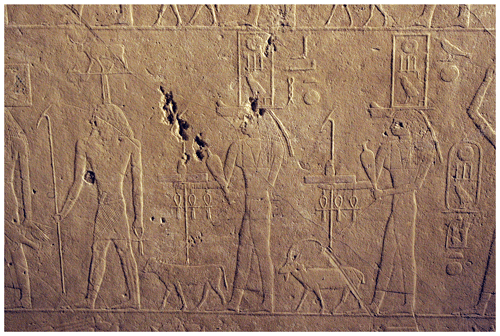

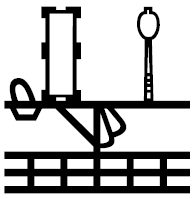

Figure 2Depiction of the 10th nome of Lower Egypt from a newly discovered block from the causeway of Sahura (photo by Martin Frouz).

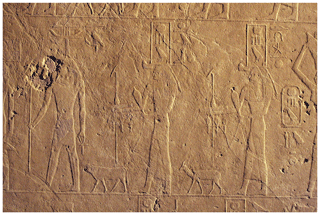

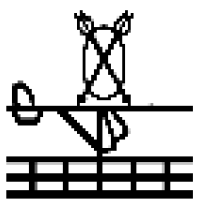

Figure 3Depiction of the western part of the seventh nome of Lower Egypt from a newly discovered block from the causeway of Sahura (photo by Martin Frouz).

Figure 4The earliest list of pehou from a newly discovered block from the causeway of Sahura drawn by Jolana Malátková based on the photo of Martin Frouz.

The depiction of the nome as a male figure occurs for the first time in the pyramid temple of Sahura, and, as in the case of Userkaf, only the standard of the nome is attested (Labrousse and Lauer, 2000, 85–86, Fig. 133a, b). Afterwards, this method of depiction became standard in the royal decorative programs of Sahura's successors. What remains unclear is the depiction of a female personification of a nome in the same scenes, which opens a new debate on the attestation of nomes in the form of males and females. Of course, this leads to the suggestion that the depiction of these figures is found only in scenes from the pyramid temple as female personifications as nomes have not yet been discovered in the recently excavated scenes from the causeway. Future exploration of the remaining blocks should clarify this unresolved dilemma.

Additional scenes of nomes are attested on an alabaster altar in the open courtyard on which offerings were presented to the deceased king. These scenes consist of the personifications of male and female figures representing the nomes of Egypt (Megahed, 2014, 58).

1.1 Nomes of Lower Egypt in the Old Kingdom

The late Greco-Roman temples introduced Egyptology to the list of nomes

with their division by mr, “canal”, ww, “farmland”, and ![]() , “swamp”

(Gauthier, 1935; Helck, 1974; Leitz,

2014, 69–126, plate 1b). They usually take the shape of personified male or

female figures, and they sometimes carry offerings. Above their head is the

sign of the nome that they represent, which is depicted on a standard.

, “swamp”

(Gauthier, 1935; Helck, 1974; Leitz,

2014, 69–126, plate 1b). They usually take the shape of personified male or

female figures, and they sometimes carry offerings. Above their head is the

sign of the nome that they represent, which is depicted on a standard.

Jacquet-Gordon (1962, 113) believed that the lists of the nomes from the Old Kingdom to the New Kingdom are different in several aspects from the standard list of later periods. She added that the reasons behind such changes are vague, and they were perhaps due to some administrative requirements.

The new discovery from the northern wall of the causeway of Sahura presents two more nomes of Lower Egypt in addition to the already known Lower Egyptian nomes depicted on the walls of the pyramid temple. Furthermore, the above-mentioned so-called pehou list, which brings up the rear of the procession of the funerary domains of Sahura, represents the northern border of the Lower Egyptian nomes. It is the only example of the listing of pehou areas from the Old Kingdom.

Comprehensive information regarding the nomes of Lower Egypt during the Old Kingdom can be derived from different sources. First, there are the royal monuments, such as pyramid complexes belonging to Snefru, Userkaf and Sahura, or the solar temple of Niuserra where nearly complete lists of Lower Egyptian nomes are attested (von Bissing, 1955, 319–38; Kees, 1956, 33–40; Nuzzolo, 2018, 188–198; Seyfried, 2019, 39–42, plates 1–3). Second, there are non-royal tombs where several other nomes from the delta also occur. Nevertheless, only the symbol of the nomes was depicted on a standard. These are usually portrayed within the procession of the funerary domains, referring to the location of the domains that follow. Most of them are incorporated with a royal name. However, in a few cases, nomes also are attested with some private names in the non-royal tombs, such as the tomb of Nikaura (L.G. 87; G 8158), which is attributed to the reign of Khafra (Jacquet-Gordon, 1962, 219–221), and the tombs of Akhethotep and Ptahhotep II (D 64), which are attributed to the reign of Djedkara (Griffith and Davies, 1900, 8–9, plate 13; Baer, 1960, 75 [161]; Strudwick, 1985, 88 [50]; Harpur, 1987, 274 [400]). The tomb of Kairer is attributed to the reign of Unas and Teti (Jacquet-Gordon, 1962, 428–429). The tomb of Sabu/Ibebi (E1, 2+ H3) dates back to the reign of Teti (Baer, 1960, 118 [402]; Strudwick, 1985, 128 [113]; Harpur, 1987, 216–217; El-Khadragy, 2005, 169–199, plates 16–19). The tomb of Khnumenti (G 2374) was created in the reign of Teti (Jacquet-Gordon, 1962, 310–312; Brovarski, 2001, 122–123, plate 92, Fig. 87a). The tomb of Hesi is attributed to the reign of Pepi I (Kanawati and Abder-Raziq, 1999, 13:42, plate 62); however, Silverman (2000, 1–13; Kloth, 2002, 25–26) attributed it to the reign of Teti. Correspondingly, the tomb of Mehou dates to the reign of Pepi I (Baer, 1960, 83 [202]; Strudwick, 1985, 101–102 [69]; Harpur, 1987, 274 [424]), while Altenmüller (1998, 202–205), on the other hand, dates the tomb to the reign of Teti.

Furthermore, nomes are sometimes attested in the autobiography and the titles of the high officials who were in charge of such nomes in the delta; for example, in the biographical inscription of Metjen (tomb: L.S. 6) (Goedicke, 1966, 1–71) and Pehernefer (Junker, 1939, 63–84).

In addition to the nomes attested in the royal annals on the Palermo stone, the Abusir Papyri and other written documents are useful here as will be shown in the following survey.

1.1.1 The first nome

Royal complexes: the first nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the pyramid complex of Sahura (Borchardt, 1913, 42, 105, plate 26). A possible likeness of the same depiction was found in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

However, it is not clear since it does not appear on top of a standard like the other nomes (von Bissing, 1955, 321, plates 3, 4; Nuzzolo, 2018, 188–198; Seyfried, 2019, plate 3).

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the first nome has appeared in the royal annals of Sahura on the Palermo stone (Wilkinson, 2000, 160–161).

Non-royal tombs: the first nome has appeared in the tomb of Akhethotep (D 64) with a private domain incorporated with his name; however, the nome is not depicted on a standard.

1.1.2 The second nome

Royal complexes: the second nome of Lower Egypt has been depicted in the pyramid complex of Userkaf (Labrousse and Lauer, 2000, 88, Doc. 62, Fig. 134a–b).

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the second nome has been attested in the biographical inscription of Metjen. Also, it occurs in the Abusir Papyri in an administrative title (Posener-Kriéger, 1976, 595).

Non-royal tombs: the second nome appears in the tombs of Akhethotep (D 64) on a standard in front of two Hwt centers incorporated with the name of king Isesi, of Ptahhotep II with a private name of a domain, of Sabu/Ibebi with a domain with the name of king Teti, of Khnumenti with the names of both kings Unas and Teti, and of Hesi with the name of king Teti.

1.1.3 The third nome

Royal complexes: the third nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the third nome can be found in the biographical inscription of Metjen.

Non-royal tombs: the third nome occurs in the procession of the funerary domains of the tombs of Akhethotep (D 64) on a standard followed by two domains incorporated with the name of Isesi and his queen Setibhor (Megahed, 2011, 616–634; Megahed et al. 2019, 44), of Ptahhotep II and also incorporated with the name of queen Setibhor, of Kairer with the name of Teti, of Sabu/Ibebi with the name of Teti, of Khnumenti with the name of Teti, of Hesi with the name of Teti, and of Mehou incorporated with the names of Isesi, Unas and Teti in addition to a private domain incorporated with his name.

1.1.4 The fourth and fifth nomes

Royal complex: both the fourth and fifth nomes of Lower Egypt have been attested in the pyramid complex of Niuserra (Jacquet-Gordon, 1962, 155), as well as in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the fourth and fifth nomes have occurred in the biographical inscription of Metjen. Also, they have been attested in an administrative title in the Abusir Papyri of the Fifth Dynasty (Posener-Kriéger, 1976, 594).

Non-royal tombs: the fourth and fifth nomes have appeared in the tomb of Khnumenti preceding a domain incorporated with the name of Teti. Also, they can be found in the tomb of Hesi above a name of a domain incorporated with the name of Teti.

1.1.5 The sixth nome

Royal complex: the sixth nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the pyramid complex of Userkaf (Labrousse and Lauer, 2000, 87–88, DOC. 61 A–C, Fig. 133a, b). Another depiction can be seen in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab in addition to the last available attestation of this nome in the time of the Old Kingdom in the pyramid complex of Unas (Labrousse and Moussa, 2002, 97–98 Doc. 107, Fig. 139, plate 19a.).

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the sixth nome has occurred in the biographical inscription of Metjen.

Non-royal tombs: the sixth nome has appeared in the tomb of Hesi above a name of a domain incorporated with the name of Teti.

1.1.6 The seventh nome (west)

Royal complex: the seventh nome of Lower Egypt has been attested on the newly discovered blocks from the northern side of the causeway of Sahura. Also, it has appeared in the pyramid complex of Unas, but it is worth noting that Jacquet-Gordon marked it as the 11th nome of Lower Egypt (Jacquet-Gordon, 1962, 173). Labrousse and Moussa (2002, 98–99 Doc. 108, Fig. 140), on the other hand, believed that this nome is the eighth Lower Egyptian nome. However, based on our new list, we can conclude now that the seventh nome (west) is the best candidate since the same nome is attested in the procession of domains in the non-royal tombs incorporated with the name of Unas. In contrast, the eighth nome with the name of Unas never occurs.

Non-royal tombs: the seventh nome (west) appears in the tomb of

Akhethotep (D 64) on a standard followed by eight domains, two of which are in

the form of Hwt incorporated with the name of Niuserra, while the rest are

depicted in the form of ![]() incorporated with the name of Userkaf (once,

possibly twice through reconstruction) and Isesi (four times). It is also

noteworthy that the writing of the name in the tomb shows a different

writing for the sign for the west, Z 11 in Gardiner's sign list

(Gardiner, 1957). Also, the name has been attested in the tomb of

Kairer preceding the name of two domains incorporating the names of Unas and

Teti. In the tomb of Khnumenti, it appears incorporated with the name of

Teti and, in the tomb of Hesi, with the name of Teti. Finally, it can be seen in

the tomb of Mehou incorporated with the birth names of Niuserra (Ini), Unas

and Teti.

incorporated with the name of Userkaf (once,

possibly twice through reconstruction) and Isesi (four times). It is also

noteworthy that the writing of the name in the tomb shows a different

writing for the sign for the west, Z 11 in Gardiner's sign list

(Gardiner, 1957). Also, the name has been attested in the tomb of

Kairer preceding the name of two domains incorporating the names of Unas and

Teti. In the tomb of Khnumenti, it appears incorporated with the name of

Teti and, in the tomb of Hesi, with the name of Teti. Finally, it can be seen in

the tomb of Mehou incorporated with the birth names of Niuserra (Ini), Unas

and Teti.

1.1.7 The seventh/eighth nome (harpoon)

Royal complex: the seventh and eighth nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the name of the seventh/eighth nome has appeared in the biographical inscription of Metjen. The name of the harpoon nome is also attested on Ostracon Leiden J 427 (Goedicke, 1968, 27).

Non-royal tombs: the name of the seventh/eighth nome has been

attested three times in the tomb of Ptahhotep II (D 64) incorporated with

the name of Sahura followed by a domain in the form of Hwt and with the

names of Ikauhor and Isesi, followed by domains in the form of ![]() .

.

1.1.8 The eighth nome

Royal complex: the eighth nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the pyramid complex of Pepi II as a sign on a standard preceding two domains in the form of Hwt (Jéquier, 1940, plate 25).

Non-royal tombs: the name of the eighth nome has been attested in the tomb of Mehou incorporated with the name of Isesi.

1.1.9 The ninth nome

Royal complex: the ninth nome of Lower Egypt has never been attested in any royal complexes of the Old Kingdom; however, it appeared as a name of a pehou from the newly discovered blocks from the causeway of Sahura (Khaled, 2018, 238–239, Fig. 1).

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the name of the ninth nome has been attested in the biographical inscription of Pehernefer (Junker, 1939, 68 Nr. 24). Also, it occurred in the royal annals of Sahura on the Palermo stone (Wilkinson, 2000, 160–161).

Non-royal tombs: the ninth nome has been attested twice in the procession of the funerary domains in the tomb of Ptahhotep II (D 64) incorporated with the names of Userkaf and the sanctuary of Nekhen Osiris. It also appeared in the tomb of Kairer with the name of Teti preceding a domain in the form of Hwt and in the tomb of Hesi incorporated with the names of Unas and Teti. Finally, it can be found in the tomb of Mehou incorporated with the name of Teti.

1.1.10 The 10th nome

Royal complex: the 10th nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the pyramid complex of Sahura (Borchardt, 1913, 42, 105, plate 31), as well as in the newly discovered blocks from the northern side of the causeway of Sahura. The same depiction can be found in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the name of the 10th nome has occurred in the royal annals of Sahura on the Palermo stone (Wilkinson, 2000, 160–161).

Non-royal tombs: The 10th nome has occurred twice in the procession of the funerary domains in the tomb of Ptahhotep II (D 64) incorporated with the names of Snefru and the birth name of Neferirkara (Kakai); unfortunately, the nome sign is destroyed so that only the rear part of the bull can still be seen. Jacquet-Gordon (1962, 401, 13) reconstructed this nome as the 12th nome; however, based on this present study, it is apparent that this nome is either the 10th or 11th Lower Egyptian nome. Also, the name of the 10th nome has been attested in the tomb of Hesi incorporated with the name of Unas and Teti. Moreover, the same depiction of the bull alone on a standard is depicted in the tomb of Mehou with two domains incorporated with the name of Teti. Jacquet-Gordon (1962, 424, 25) reconstructed this nome as the 12th nome. At any rate, it is far more likely that this depiction also shows the 10th nome since the name of the domain is similar to the name of the domain in the tomb of Hesi.

1.1.11 The 11th nome

Royal complex: the attestation of the 11th nome of Lower Egypt has occurred in the pyramid complex of Sahura (Borchardt, 1913, 42, 105, plate 31). The nome has also been attested in the pyramid complex of Niuserra (Borchardt, 1907, plate 14), as well as in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the 11th nome has occurred in an administrative title in the Abusir Papyri (Posener-Kriéger, 1976, 594).

Non-royal tombs: the 11th nome has been attested in the tomb of Akhethotep (D 64) incorporated with the name of Djedfra, as well as in the tomb of Ptahhotep II with the name of Isesi. This depiction also occurred in the tomb of Sabu/Ibebi with the name of Teti. Jacquet-Gordon (1962, 417, 2) was confused because the bull was depicted alone on a standard, and she preferred to identify it as the 12th nome. Correspondingly, the recent publication by El-Khadragy followed Jacquet-Gordon, Still, the current study shows that this is in fact the 11th Lower Egyptian nome as a recent publication of the tomb of Hesi shows a similar name for the domain of Teti located in the 11th nome.

1.1.12 The 12th nome

Non-royal complex: the 12th nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the royal complexes, namely in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the name of the 12th nome has occurred in the biographical inscription of Pehernefer (Junker, 1939, 6).

Non-royal tombs: the 12th nome has been attested in the tomb of Ptahhotep II with a domain incorporated with the name of Isesi. Furthermore, the name of the 12th nome has also been attested in the tomb of Hesi incorporated with the name of Teti.

1.1.13 The 13th nome

The depiction of the 13th nome has not been attested in any royal complex from the Old Kingdom. The 13th and 14th nomes were both most probably united until the end of the Fifth Dynasty; consequently, both of them were split into two separate nomes after that time (Fischer, 1959, 129–142; Jacquet-Gordon, 1962, 110; Altenmüller, 1998, 124).

Non-royal tombs: the 13th nome has been attested in the tomb of Sabu/Ibebi incorporated with the name of Teti. The same nome has occurred in the tomb of Hesi with the name of Teti, as well as in the tomb of Mehou with the names of Unas and Teti, which could serve as proof that the nome was divided during the reign of Unas as this is the oldest attestation.

1.1.14 The 13th/14th nome (east nome)

Royal complex: the two nomes have been attested before the division in the pyramid complex of Snefru (Fakhry, 1961, 50. Fig. 24); they are also depicted on the alabaster altar of Niuserra (Borchardt, 1907, plate 14).

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the nome has been documented in the autobiography of the official Nesutnefer (Junker, 1938, 172–175, Abb. 27).

Non-royal tombs: the two nomes have occurred before their division in the tomb of Sabu//Ibebi in the procession of his funerary domains incorporated with the names of Khafra and Isesi. This also serves as proof that, until the time of the Isesi, there was no splitting up of the 13th and 14th nomes.

1.1.15 The 14th nome

Royal complex: the 14th nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the pyramid complex of Sahura (Borchardt, 1913, 42, 105, plate 26). Another possible depiction comes from the pyramid complex of Niuserra (von Bissing, 1955, 321, plates 3, 4).

Non-royal tombs: the 14th nome has occurred in the tomb of Khnumenti with the name of Teti. Also, it occurred in the tomb of Hesi with the name of Teti. This could serve as proof that the division was already completed during the reign of Teti.

1.1.16 The 15th nome

Royal complex: the 15th nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the “room of the seasons” in the solar temple of Niuserra at Abu Ghurab.

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the nome has also been documented in the autobiography of the official Sehetepu, however, in opposition to Montet (1946, 219–220) who reads it as a name of the god Thoth.

Non-royal tombs: the 15th nome has occurred in the tomb of Kairer with the names of Unas and Teti, as well as in the tomb of Sabu/Ibebi with the names of Unas and Teti. Finally, in the tomb of Mehou, the nome precedes a number of domains of Kaki, Isesi, Unas, queen Seshseshet and Teti in addition to the name of prince Ptahshepses.

1.1.17 The 16th nome

Royal complex: the 16th nome of Lower Egypt has been attested in the royal complexes in the pyramid complex of Sahura (Borchardt, 1913, 42, 105, plate 31).

Administrative titles, royal annals, etc.: the nome has also been documented in the autobiography of the official Metjen.

Non-royal tombs: the 16th nome has occurred in the tomb of Nikaura with the name of Khafra, as well as in the tomb of Khnumenti with the name of Teti. Finally, in the tomb of Mehou the name is attested with the name of Teti and the royal mother Seshseshet.

From the current study, it is apparent that, during the reign of Niuserra, Lower Egypt had its complete division and number of nomes; in addition, the changes in the administration of high regional officials outside the Memphite region serve as other evidence of expanding the land of the delta (Willems, 2014, 20–23). As Helck mentioned, the delta contained 16 nomes by the Fifth Dynasty (Helck, 1974, 199–203). On the other hand, one can observe that the delta had only 12 nomes in the time of Sahura at the beginning of the Fifth Dynasty. Some are attested in his pyramid temple and causeway, while the others are mentioned in the non-royal tombs. Other nomes already occur prior to Sahura's reign, such as the nomes of the delta mentioned in the autobiography of Metjen and also those attested with the names of Snefru, Khafra and Userkaf.

According to Helck, the fourth and fifth nomes of Lower Egypt were counted as one nome in the Old Kingdom (Helck, 1974, 158–163). Therefore, this paper proposes that the existing nomes of Lower Egypt in the time of Sahura were only 12 in number and include the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th/5th and 6th and the west of the 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 13th/14th and 16th nomes. The new discovery of the pehou list from the causeway of Sahura somewhat confirms this number.

Scholars have already observed that the order of the nomes is not consistent, especially in the list of Niuserra in which the ninth nome is followed by the 12th and then the 11th and 10th nomes. Therefore, based on this observation, it is logical to accept variation in the names and their locations within the lists, which do not necessarily follow the numerical order of our modern view. However, it seems impossible to know the exact number of nomes, especially during the Old Kingdom, because these numbers were created according to later lists.

For example, the geographical location of the 16th nome of Lower Egypt depicted in the pyramid temple of Sahura is unknown, and this nome might have occupied the 12th position at the time of this king.

An important observation can be made, however, on the basis of the new data: the organization of the nomes was fluid in a way that the territory assigned to them and their borders was altered from time to time by the requirements of ancient Egyptian administration. The new reliefs from the causeway of Sahura at Abusir show how the kings were concerned about the geography of the country besides the important information that can be generated from the scenes that the territory of the delta was growing and expanding very quickly. Kings used to expand the borders of an existing nome and to create new establishments. Consequently, these establishments were united or divided into new nomes. (See above the division of the 13th and 14th nomes.) This could also serve as evidence for the changes in the names of the list of nomes. Of course, future excavation and discoveries will add more new information to the subject.

All data relevant for this contribution are presented within the article itself (see Sects. 1 and 2).

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Geoarchaeology of the Nile Delta”. It is a result of the workshop “Geoarchaeology of the Nile Delta: Current Research and Future Prospects”, Würzburg, Germany, 29–30 November 2019.

This article was completed within the framework of the DFG project ID 389349558 (see https://gepris.dfg.de/gepris/projekt/389349558, last access: 8 July 2020). “Archäologie des ägyptischen Staates und seiner Wirtschaft im 3. Jahrtausend v. Chr.: eine neue Untersuchung des Sahurê-Aufwegs in Abusir”.

This open-access publication was funded by

Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg.

This paper was edited by Eva Lange-Athinodorou and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Altenmüller, H.: Die Wanddarstellungen Im Grab Des Mehu in Saqqara, Archäologische Veröffentlichungen 42, Mainz am Rhein, von Zabern, 1998.

Baer, K.: Rank and Title in the Old Kingdom: The Structure of the Egyptian Administration in the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Borchardt, L.: Das Grabdenkmal Des Königs Ne-User-Re', Leipzig, Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, 1907.

Borchardt, L.: Das Grabdenkmal Des Königs S'ahu-Re. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1910.

Borchardt, L.: Das Grabdenkmal Des Königs Sahu-Re: Abbildungsblätter, Leipzig: Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, 1913.

Brovarski, E.: The Senedjemib Complex. Pt. 1, [Ill.]: The Mastabas of Senedjemib Inti (G2370), Khnumenti (G2374), and Senedjemib Mehi (G2378), Giza Mastabas 7, Boston, Art of the Ancient World, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2001.

Fakhry, A.: The Monuments of Sneferu at Dahshur II. The Valley Temple, Part I. The Temple Reliefs, Cairo: General Organization for Government Printing Offices, 1961.

Fischer, H. G.: Some Notes on the Easternmost Nomes of the Delta in the Old and Middle Kingdoms, in: Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 18, 129–42, 1959.

Gardiner, A. H.: Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Third revised edition, London, Oxford University Press, 1957.

Gauthier, H.: Les Nomes d'Égypte Depuis Hérodote Jusqu'à La Conquête Arabe, Vol. 25. Mémoires de l'Institut d'Égypte, Le Caire: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 1935.

Goedicke, H.: Die Laufbahn Des MTn: in: Mitteilungen Des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo, 21, 1–71, 1966.

Goedicke, H.: Four Hieratic Ostraca of the Old Kingdom, J. Egypt. Archaeol., 54, 23–30, 1968.

Griffith, F. Ll. and Davies, N. de G.: The Mastaba of Ptahhetep and Akhethetep at Saqqareh, Vol. 8–9. 2 vols. Archaeological Survey of Egypt, London, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1900.

Harpur, Y.: Decoration in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom: Studies in Orientation and Scene Content, Studies in Egyptology, London; New York: New York, NY, USA: KPI; Distributed by Methuen, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1987.

Helck, W.: Die Altägyptischen Gaue, TAVO, B/5, Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert, 1974.

Jacquet-Gordon, H.: Les Noms Des Domaines Funéraires Sous l'Ancien Empire Égyptien. BdÈ 34, Caire: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, 1962.

Jéquier, G.: Le Monument Funéraire de Pepi II: Tome 3. Les Approches Du Temple. Fouilles à Saqqarah, Le Caire: l'Institut francais d'archeologie orientale, 1940.

Junker, H.: Giza III: Bericht Über Die von Der Akademie Der Wissenschaften in Wien Auf Gemeinsame Kosten Mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus Unternommenen Grabungen Auf Dem Friedhof Des Alten Reiches Bei Den Pyramiden von Giza. Band III, Die Mastabas Der Vorgeschrittenen V. Dynastie Auf Dem Westfriedhof, Wien – Leipzig: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1938.

Junker, H.: PHrnfr, in: Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 75, 63–84, 1939.

Kanawati, N. and Abder-Raziq, M.: The Teti Cemetery at Saqqara. Volume V: The Tomb of Hesi. Vol. 13. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Reports, Warminster: Aris & Phillips, 1999.

Kees, H.: Zu Den Gaulisten Im Sonnenheiligtum Des Neuserrê, in: Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 81, 33–40, 1956.

El-Khadragy, M.: The Offering Niche of Sabu/Ibebi in the Cairo Museum, in: Studien Zur Altägyptischen Kultur, 33, 169–99, 2005.

Khaled, M. I.: The Old Kingdom Royal Funerary Domains: New Evidence from the Causeway of the Pyramid Complex of Sahure, PhD thesis, Prague: Charles University in Prague (PhD dissertation), 2008.

Khaled, M. I.: The Earliest Attested Pehou List in the Old Kingdom, in: The Art of Describing: The World of Tomb Decoration as Visual Culture of the Old Kingdom. Studies in Honour of Yvonne Harpur, edited by: Peter Jánosi and Hana Vymazalová, Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts, 235–247, 2018.

Kloth, N.: Die (Auto-) Biographischen Inschriften Des Ägyptischen Alten Reiches: Untersuchungen Zur Phraseolohgie Ung Entwicklung, SAK 8, Hamburg: Buske, 2002.

Labrousse, A. and Lauer, J. P.: Les Complexes Funéraires d'Ouserkaf et de Néferthétepès. BdE 130, Le Caire, Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 2000.

Labrousse, A. and Moussa, A. M.: La Chaussée Du Complexe Funéraire Du Roi Ounas. BdE 134, Le Caire: Institut francais d'archéologie orientale, 2002.

Leitz, C.: Geographische Soubassementtexte Aus Griechisch-Römischer Zeit Eine Hauptquelle Altägyptischer Kulttopographie, in: Altägyptische Enzyklopädien, Die Soubassements in Den Tempeln Der Griechisch-Römischen Zeit, Studien Zur Spätägyptischen Religion 7, Wiesbaden, I, 69–126, 2014.

Megahed, M.: The Pyramid Complex of Djedkare's Queen' in South Saqqara Preliminary Report 2010, in: Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010, edited by: Bárta, M., Coppens, F., and Krejčí, J., Prague, Czech Institute of Egyptology Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, 616–634, 2011.

Megahed, M.: The Altar of Djedkare's Funerary Temple, from South Saqqara, in: Cult and Belief in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress for Young Egyptologists, 25–27 September 2012, Sofia, edited by: Lekov, T. and Buzov, E., Sofia: Bulgarian Institute of Egyptology, New Bulgarian University, 56–62, 2014.

Megahed, M., Hashesh, Z., Jánosi, P., and Vymazalová, H.: Djedkare-Isesis Pyramidenkomplex: Grabungskampagnen 2018, in: Sokar 38, 24–49, 2019.

Montet, P.: Tombeaux de La Ière et de La IVe Dynasties à Abou-Roach: Deuxième Partie, Inventaire Des Objets, in: Kêmi, 8, 157–227, 1946.

Nuzzolo, M.: The Fifth Dynasty Sun Temples: Kingship, Architecture and Religion in Third Millenium BC Egypt, Prague: Charles University Faculty of Arts, 2018.

Posener-Kriéger, P.: Les Archives Du Temple Funéraire de Néferirkare-Kakai (Les Papyrus d'Abousir): Traduction et Commentaire I-II. BdÈ 65, Caire: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, 1976.

Seyfried, K. J.: Jahreszeitenreliefs Aus Dem Sonnenheiligtum Des Koenigs Ne-User-Re, 1st edition, Boston, MA, De Gruyter, 2019.

Silverman, D.: The Threat Formula and Biographical Text in the Tomb of Hezi at Saqqara, in: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 37, 1–13, 2000.

Strudwick, N.: The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders, Studies in Egyptology, London, KPI, 1985.

von Bissing, F. W.: La Chambre Des Trois Saisons Du Sanctuaire Solaire Du Roi Rathourès (Ve Dynastie) à Abousir, in: Annales Du Service Des Antiquités de l'Égypte, 53, 319–38, 1955.

Wilkinson, T.: Royal Annals of Ancient Egypt: The Palermo Stone and Its Associated Fragments, Studies in Egyptology, London, Kegan Paul International, 2000.

Willems, H.: Historical and Archaeological Aspects of Egyptian Funerary Culture: Religious Ideas and Ritual Practice in Middle Kingdom Elite Cemeteries, Culture and History of the Ancient Near East, volume 73, Leiden, Boston, Brill, 2014.