the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The geomorphological and sedimentological legacy of the historical Lake Lorsch within the Weschnitz floodplain (northeastern Upper Rhine Graben, Germany)

Felix Henselowsky

Peter Fischer

Elena Appel

Barbara Jäger

Nicolai Hillmus

Helen Sandbrink

Thomas Becker

Roland Prien

Gerrit Jasper Schenk

Bertil Mächtle

Udo Recker

Olaf Bubenzer

Andreas Vött

Henselowsky, F., Fischer, P., Appel, E., Jäger, B., Hillmus, N., Sandbrink, H., Becker, T., Prien, R., Schenk, G. J., Mächtle, B., Recker, U., Bubenzer, O., and Vött, A.: The geomorphological and sedimentological legacy of the historical Lake Lorsch within the Weschnitz floodplain (northeastern Upper Rhine Graben, Germany), E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 75, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-75-1-2026, 2026.

The artificial historical Lake Lorsch (1474/1479 to 1718/1720 CE) in the northeastern Upper Rhine Graben (Germany) is known from various historical sources (e.g., for fish farming) as a significant anthropogenic imprint of the Weschnitz floodplain. Nevertheless, there have been no geomorphological and sedimentological investigations into the (quasi-)natural context for the creation of the lake, its importance as a potential sediment archive and the subsequent use of the lake area until modern times. No relics of the lake can be observed in today's landscape. We investigated the geomorphological setting of the area using a high-resolution digital elevation model, groundwater-level data, and geophysical prospection, as well as sedimentological information from four sediment cores. Results indicate that the location of the lake is topographically deeper in relation to its receiving waters of the old Weschnitz and that Lake Lorsch was fed by groundwater. Sedimentary analysis (core LOR 21A, unit 2; LOSE 4 and LOSE 5, unit 3) exhibits lake deposit, with characteristics indicative of a limnic environment and a high groundwater table. At the same time, adjacent stratigraphy shows channel deposits (core LOR 20A, unit 3), reflecting an anthropogenically controlled inflow via a channel (Renngraben). Our results, based on a relative elevation model, fit well with the historical records: that the inflow for the anthropogenic channel was via the old Weschnitz (topographically higher than the lake area) and that the artificial Landgraben canal (topographically lower than the lake area) was crossed by a water bridge. It is a good example of how humans have acted as fluvial- and water-related agents for at least 500 years in the Weschnitz floodplain.

Der anthropogen angelegte historische Lorscher See (1474/1479 bis 1718/1720 n. Chr.) im nordöstlichen Oberrheingraben (Deutschland) ist aus verschiedenen historischen Quellen, z. B. zur Fischzucht, als bedeutende anthropogene Prägung der Weschnitzaue bekannt. Dennoch fehlen geomorphologische und sedimentologische Untersuchungen über den (quasi-)natürlichen Kontext der Entstehung des Sees, seiner Bedeutung als potentielles Sedimentarchiv und die Nachnutzung des Seegebietes bis in die Neuzeit. Heute sind keine Relikte des Sees mehr in der Landschaft zu beobachten. Mit Hilfe eines hochaufgelösten digitalen Geländemodells, Grundwassersdaten, geophysikalischer Prospektion sowie sedimentologischen Analysen aus vier Bohrkernen haben wir die geomorphologischen Gegebenheiten des Gebiets untersucht. Daraus lässt sich ableiten, dass der Standort des Sees topographisch tiefer liegt als sein Vorfluter, die Weschnitz, und stark grundwassergespeist war. Die Sedimentanalyse (Kern LOR 21A, Einheit 2; LOSE 4 und LOSE 5, Einheit 3) zeigt Seeablagerungen mit Merkmalen, die auf ein limnisches Umfeld und einen hohen Grundwasserspiegel hinweisen. Gleichzeitig deuten die angrenzenden Ergebnisse (Kern LOR 20A, Einheit 3) auf Rinnenablagerungen eines anthropogen gesteuerten Zuflusses über einen Kanal (Renngraben) hin. Unsere Ergebnisse basierend auf einem relativen Geländemodell passen gut zu den historischen Aufzeichnungen über die Nutzung des Lorscher Sees die belegen, dass der Zufluss für den anthropogenen Kanal über die Alte Weschnitz (der topographisch höher als das Seegebiet liegt) erfolgte und dass der künstliche Landgraben-Kanal (topographisch tiefer als das Seegebiet) mit einer Brücke überströmt wurde. Die Untersuchungen sind ein exzellentes Beispiel dafür, in welchem Maße der Mensch seit mehr als 500 Jahren das hydrologische System in der Weschnitzaue und seinen angrenzenden Regionen beeinflusst hat.

- Article

(10827 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

River floodplains are highly dynamic landscapes and important nodes for livelihood, innovation and conflict in the history of a settlement (Werther et al., 2021). European floodplains in particular have been transformed over very long periods of time by natural and anthropogenic processes. Floodplains are almost undeveloped for large parts of the Holocene. Only since the mid to late Holocene – mainly due to increased soil erosion caused by deforestation and agriculture – have typical overbank silt-clay deposits with the disappearance of former wetlands existed (Brown et al., 2018). These changes started after 1000 years BCE with several engineering technologies (Gibling, 2018). Larger interventions have occurred in an initial phase since the Middle Ages and significantly with the industrialization of rivers in the technological era, starting around 1800 CE (Gibling, 2018). Based on these conditions, today it is often almost impossible to reconstruct the natural conditions (Brown et al., 2018). However, it is crucial to understand the long-term impact of human activity on fluvial systems, in particular in the context of contemporary river restoration measures (Maaß et al., 2021).

As part of the DFG Priority Program (SPP 2361) “On the Way to the Fluvial Anthroposphere”, we study the development of floodplain landscapes of German medium-sized rivers during the Middle Ages and the early modern period (Henselowsky et al., 2024). The river Weschnitz in the Upper Rhine Graben (URG) in southwestern Germany is the largest river entering the southern Hessisches Ried, a landscape representative of a coupled human–water system. Hydrological changes characterized by high groundwater tables, natural fluvial processes and anthropogenic impacts have influenced historical human–environment interactions. Since Roman times, river regulation and water management in the Hessisches Ried have affected the floodplain of several natural river courses, including the construction of anthropogenic watercourses (e.g., Hanel, 1995; Heising, 2012; Appel et al., 2024a, b) and the particular location of fortifications, exemplified by the Roman fortlet and medieval lowland castle at the Zullestein site (Prien et al., 2025).

Whereas a very early diversion of the Weschnitz River during Roman times was discussed, but refuted recently (Helfert, 2014; Appel et al., 2024b), the influence of human activity during the medieval period is particularly high. The foundation of the Lorsch Abbey at the start of the Carolingian period (763–764 CE) next to the Weschnitz marks the onset of the region's great supra-regional importance in Europe. The monastic library of Lorsch, Bibliotheca Laurashamensis, represents a vital contribution to the literary tradition of writings for this time frame and a center of knowledge for the early Middle Ages (Büttner and Kautz, 2015). Lorsch Abbey – a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1991 – was the legitimate power base of the Carolingians, with their dominion extending from the North Sea to south of the Alps (Schefers, 2023). As the core zone of the Holy Roman Empire, it is also possible to observe the negotiation of zones of influence between two electorates that were decisive throughout the empire (Electorate of Mainz and Electorate of Palatinate). Due to this high historical significance, a good understanding of the natural conditions under which the abbey as the center of power was created is important for transdisciplinary research, due to the strong human influence of the water-dominated floodplain landscape developing towards a fluvial anthroposphere (Schenk, 2024). This contributes to the improved understanding of how institutions and governance processes interact with hydrological processes (Di Baldassarre et al., 2013) and its impact on autonomous decisions from people and institutions about water and land management (Daniell and Barreteau, 2014).

One feature mentioned in the historical maps and sources of the local landscape surrounding the abbey is a lake that existed south of Lorsch. Although the former lake area is dry today, this so-called Lorscher See is sufficiently documented in older literature and current research, especially by historians (Lepper, 1938; Fecher, 1942; Koob, 1956; Platz, 2011; Schenk, 2024; Hillmus, 2025). The lake was, for example, very important for the supply of fish in the wider area (Schenk 2024; Lepper, 1938). As the lake is no longer present in the landscape today and its remnants are barely visible, our research targeted natural and anthropogenic factors for the creation and abandonment of Lake Lorsch. Reclamation work and anthropogenic drainage of lakes are a drastic form of human impact on ecosystems (e.g., Choinski et al., 2012), and in our case, the anthropogenic impact is even greater, as the lake was initially created by human activity. This means that the associated landscape changes are also part of landforms in the sense of anthropogenic geomorphology (Tarolli et al., 2019). The anthropogenic in- and outflows in the form of ditches represent, so far often neglected, an important feature that forced the development of human societies and affect environmental processes (cf. review by Clifford et al., 2025).

Overall, we aim to (1) identify the location of Lake Lorsch from a geomorphometric perspective by using a high-resolution digital elevation model, (2) determine the role of (past) groundwater levels, and (3) locate and characterize sedimentological remains of possible lake deposits within the identified morphometric location of Lake Lorsch. Through the additional integration of historical sources, we can compare the results from morphometry and sedimentology to see any possible link. This generally helps to determine whether the historical sources and natural scientific results are in agreement and to what extent they are suitable to detect specific landforms of interest. Overall, this addresses the legacy of Lake Lorsch, and we discuss its significance in historical times but also its contribution to the modern fluvioscape palimpsests. The overlapping of several natural and anthropogenic structures within the Weschnitz floodplain become recognizable, and the different features show certain path dependencies.

2.1 Natural environment

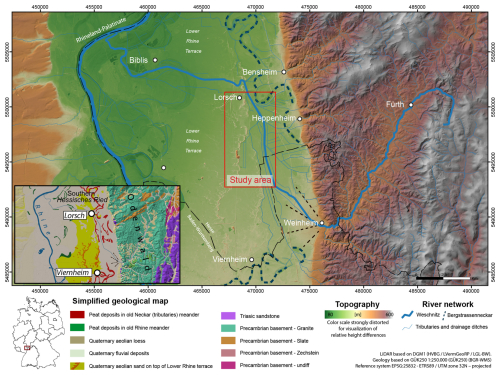

The general geological and geomorphological setting of the southern Hessische Ried with its location in the northeastern URG and the associated graben shoulder of the Odenwald Mountains is given in numerous regional studies (e.g., Dambeck and Thiemeyer, 2002; Pflanz et al., 2022; Appel et al., 2024b). The river Weschnitz has its source in the Odenwald Mountains at a height of 465 m a.s.l. and has a total length of 58.9 km with a catchment area of 438 km2. At the Lorsch River gauge, the average discharge during the years 1985 to 2025 is MQ 3.2 m3 s−1, max. observed discharge of HHQ 48.7 m3 s−1 and a mean high-discharge MHQ of 25 m3 s−1 (HLNUG, 2025). After a short course northward, the Weschnitz flows in southwesterly direction near Fürth and enters the URG at the city of Weinheim, with a large alluvial fan of Pleistocene age (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1988) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1Topographical overview of the Weschnitz catchment between the Odenwald Mountains and Upper Rhine Graben with a simplified geological map (general geological map of Germany 1 : 200 000 (GUEK200), modified after Engel et al., 2022). LiDAR based on DGM1 (HVBG/LVermGeoRP/LGL-BW). Reference system EPSG: 25832 – ETRS89/UTM zone 32N – projected.

Within the URG, the Weschnitz flows in northwestern and northern directions, parallel to the dune belt atop of the Lower Terrace of the river Rhine. During Holocene times, the Weschnitz followed a wider channel of the so-called Bergstraßenneckar (BSN), which represents the course of the Neckar between Heidelberg and the Palaeo-Neckar mouth near Trebur, until the onset of the Holocene (Dambeck and Bos, 2002; Dambeck and Thiemeyer, 2002; Bos et al., 2008; Engel et al., 2022; Appel et al., 2024b). In the area around Viernheim, the URG shows the largest accommodation space and depocenter for Quaternary sediments (the so-called Heidelberg basin) due to strong tectonic subsidence (Hoselmann, 2009; Gegg et al., 2024). This correlates with the absence of a clear BSN palaeo-meander between Weinheim and Heppenheim (Fig. 1) and is evidenced by low-sinuosity palaeo-channels of the BSN depicted on historical maps (Mangold, 1892).

At around 3000 BC, the Weschnitz changed its course near the city of Lorsch, cutting through the Lower Terrace towards its current mouth near Biblis (Appel et al., 2024b; Prien et al., 2025). Today, the floodplain of the Weschnitz is accompanied by numerous anthropogenic channels and dikes, some of them dating back to historical times. Here, the most important anthropogenic river courses are the so-called old Weschnitz, whose construction date is unknown, and the so-called new Weschnitz and the Landgraben, constructed between 1535 and 1544 (Koob, 1956). Some palaeo-channels of its original course are still visible on satellite images.

The study site is situated between two dune belts: a western one with dunes up to 10 m high and a smaller dune belt towards the eastern border of former Lake Lorsch, with dunes up to 6 m high. The dunes are part of a large eolian field between Viernheim and Lorsch, about 25 km long and 7 km wide. The dunes in the URG on top of the Lower Rhine Terrace are of late-glacial age (Holzhauer et al., 2017; Pflanz et al., 2022).

Hydrologically, the Hessische Ried is characterized by a high natural groundwater level and a large regional groundwater reservoir within the Quaternary sand and gravels of the URG (Wirsing and Luz, 2007). However, the natural groundwater level and the fluvial architecture were locally affected by melioration measures by Landgraf Georg I (1547–1596) as well as Count Palatine Ludwig V (1478–1544) during the 16th century (Noack, 1966; Koob, 1956), the Rhine rectification by Johann Gottfried Tulla between 1817 and 1876 and an associated river incision with accompanied groundwater lowering (Rösch, 2009), and more intensive melioration measures (Generalkulturplan) between 1933 and 1939 (Hanel, 1995). The most significant interventions affecting the groundwater aquifers have taken place since the 1960s in the context of abstraction for drinking water and integrated agricultural irrigation (Hessisches Ministerium für Umwelt, ländlichen Raum und Verbraucherschutz, 2005).

2.2 Historical background

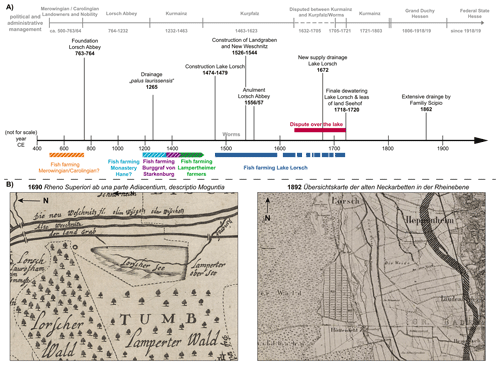

A short summary of specific important historical activities related to Lake Lorsch, based on historical sources and literature, is given in Fig. 2. Due to the natural environment, the area of Lake Lorsch was already rich in water and part of a large marshy area prior to human intervention. Before the foundation of the Lorsch Abbey between 763 and 764 CE, some sources indicate that fish farming occurred even in the early Middle Ages in the Weschnitz floodplain, although the region of the lake is not mentioned specifically (Schenk, 2021, p. 45; Codex Laureshamensis I 53; Codex Laureshamensis I 123b). It can be assumed that small lakes existed ephemerally or periodically in the swampy surroundings. This is also reflected in a document from 1265 CE, which mentions a planned drainage of the Lorsch marsh (“Palus Laurissensis”; Lepper, 1938). However, the historical sources do not directly refer to the area by name until the 15th century (Lepper, 1938; Fecher, 1942; Schenk, 2024). Since then, tt is reported that the area referred to as the Krähenbruch was used for fish farming by the Lampertheim farmers (Fecher, 1942) and that the Burgrave of Starkenburg had even constructed a lake for the same purpose before 1463 CE (Schenk, 2024).

Figure 2(A) Timeline of the historical overview of the political and administrative management in relation to Lake Lorsch and relevant historical events. (B) Details from old maps: 1690 (Nikolaus Person Rheno Superior) and 1892 (Mangold, 1892), showing the lake and post-lake phases.

In 1232 CE, Lorsch Abbey and all its possessions went to the Electorate of Mainz, so that the area of Lake Lorsch formally belonged to the Archbishop of Mainz. Subsequently, it became the subject of conflicts. It was therefore the Mainz cathedral chapter that tried to drain the Lorsch marsh in 1265 CE – probably unsuccessfully, because in the following period, people still spoke of the “bruch” (“swamp”; Lepper, 1938). In 1463 CE, there was another change of ownership when Lorsch Abbey and most of the Bergstrasse (Starkenburg district) were pledged to Count Palatine Frederick I (1425–1476). A document from Isaid Count in 1474 CE mentions the beginning of the official construction of Lake Lorsch as an artificial lake for fishing. While the charter also notes the amount of money paid to the church of Lampertheim for the usage rights, it is very likely that the fish were used to feed Friedrichsburg, which was later named Neuschloss – a hunting lodge in the Lorsch Forest where the document was signed (Schenk, 2021; 49. GLA K 67 812). Besides the “Neuschloss”, the lake could supply the court in Heidelberg with plenty of fish (Schenk, 2024; Lepper, 1938;). While the lake was fed from the southeast by an inflow from the Weschnitz, the water in the north flowed back into the Landgraben. It is also known that the lake was not continuously filled – there were times when it was drained completely to guarantee the quality of the lake water and to use it as a pasture (Fecher, 1942; Lepper, 1938). The information on the time frames for dry and filled periods ranges from every 3 years to “from time to time” (Lepper, 1938; Fecher, 1942, p. 43). Lake Lorsch was dry throughout the years 1595 to 1609 CE. In the following period, Lake Lorsch was repeatedly drained for 1 or more years (e.g., Lepper, 1938: the years 1599–1611, 1669, 1699, 1702, 1707, 1709, 1719), although the exact dates differ.

The year 1623 CE marked the beginning of a decades-long dispute over the ownership rights and the exact size of Lake Lorsch between the electors of Mainz and the Palatinate. Many of the boundary stones marking the maximum western extent of the Lake following this legal dispute can still be found in the lake area today (Schenk, 2024). Starting in 1718 CE, the Elector of Mainz had the lake finally drained, and in 1721 it was finally abandoned. From then, the area was used as a meadow and farmland, which was henceforth called “Seehof”, i.e., Hofgut am See (Lepper, 1938). However, the low yield of the land, its fragmentation through inheritance of the following generations and the growing population in a very poor economic situation led to a decision, and people from Seehof started to emigrate to America between 1852 and 1855 CE. The subsequent utilization was difficult, and the area was sold to the family Scipio with the condition that all remaining inhabitants of Seehof had to leave their village as well (Lepper, 1938). With great effort, the Scipio family had the Seehof area leveled and drained, completing the modern drainage and supply in 1862 CE.

3.1 GIS

The topographic relation between the proposed lake area with its surroundings in terms of height above/below the Weschnitz floodplain is used as a geomorphometric parameter derived from the LiDAR-based high-resolution 1 m digital elevation model (DEM) from Baden-Württemberg and Hessen (DGM1: HVBG/LVermGeoRP/LGL-BW). A relative elevation model (REM) based on the documentation by Dan Coe Carto (2016; https://dancoecarto.com/creating-rems-in-qgis-the-idw-method2016 (last access: 26 October 2024), referred to Olson et al., 2014, and Slaughter and Hubert, 2014) was produced for the characterization of the floodplain from both the “old” and “new” Weschnitz by detrending the baseline elevation. The old and new Weschnitz were digitized manually, and the respective elevations of their water levels were used as the stream thalweg. This is used for the computation of the topography along the stream line using the inverse distance weighting (IDW) method. The initial DEM is subtracted from the IDW-DEM to map areas below or above the reference stream line. Herewith, areas related to the height above/below the current reference of both streams are computed. All computation steps were performed with the software QGIS 3.4.10.

3.2 Hydrology and groundwater

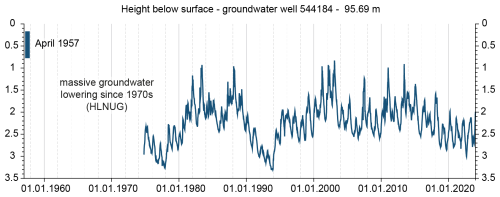

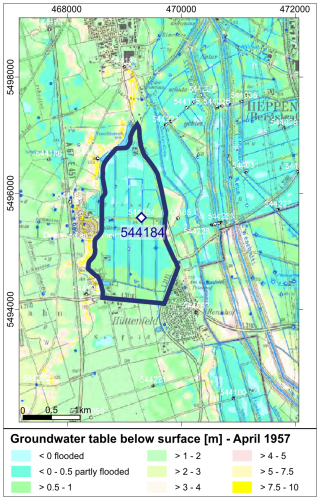

Modern groundwater changes are mapped based on the Fachinformationssystem Grund- und Trinkwasserschutz Hessen (GruSchu, https://gruschu.hessen.de/, last access: 15 January 2025) from the Hessian Agency for Nature Conservation, Environment and Geology (HLNUG). Area-wide maps for the depth of the groundwater table in the Hessisches Ried exist for single years, starting in 1957, whereas groundwater data from single wells start being collected in the 1970s. Weekly groundwater data from well 544184 (Lorsch), located in the central part of our study area, are extracted from GruSchu for the period 7 October 1974 to 30 December 2024. Although these data do not represent the actual groundwater levels in historical times, they give an impression of the general groundwater dynamics in the area.

3.3 Field investigations and sedimentological analysis

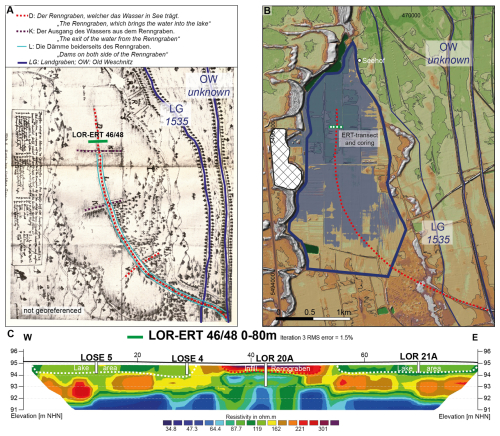

Sedimentological and stratigraphic investigations were carried out across a transect at the central part of the proposed Lake Lorsch following a historical map from 1700 (Lepper, 1938), which shows a large water supply channel (Renngraben; Fig. 6A).

3.3.1 Geophysical prospection using electrical resistivity measurements (ERT)

Geophysical prospection allows a non-invasive 2-D profile for subsurface prospection with the aim of studying the different stratigraphic and sedimentological structures. At the field site, ERT was done using a multi-electrode geophysical device (Syscal R1 Plus Switch 48, Iris Instruments) with two profiles using a Wenner–Schlumberger configuration, with an electrode spacing of 1 m (following Kneisel, 2003) for ERT transect 46 and 48 (Fig. 6C). The two ERT profiles were inverted and merged with RES2DINV software by applying least-squares inversion using a quasi-Newton method (Loke and Barker, 1996).

3.3.2 Direct push hydraulic profiling (DP-HPT)

Direct push logging allows an in situ measurement of different parameters (e.g., electrical conductivity, injection pressure, soil color) as minimal invasive subsurface prospection with real-time stratigraphic information during (geoarchaeological) fieldwork (e.g., Fischer et al., 2016; Rabiger-Völlmer et al., 2020). DP-HPT logging was conducted with a Geoprobe 540 MT system mounted on an automotive drill rig (type RS 0/2.3, Nordmeyer) and a K6050 hydraulic profiling tool (HPT, Geoprobe). The probe measures electrical conductivity (EC) with a Wenner array of four linear electrodes. Above the electrodes, water is injected at a constant flow rate through an injection screen, and hydraulic pressure is measured (McCall, 2011; Geoprobe Systems, 2015). Pre- and post-log calibration at the surface and measurement of the hydrostatic pressure in the groundwater by dissipation tests allows a correction of the total pressure (Ptotal) with the atmospheric (Patm) and hydrostatic pressure (Phydro), resulting in the corrected injection pressure (Pcorr). Data acquisition for EC and hydraulic pressure is at 2 cm vertical resolution.

3.3.3 Sediment coring

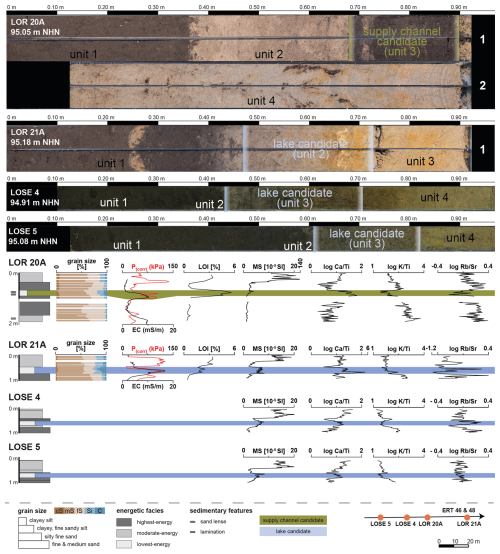

Sediment cores with closed steel augers (1 m) in combination with plastic liners (50 mm diameter) were collected at the same location as DP sensing with an automotive drill rig (type RS 0/2.3, Nordmeyer). The two master cores LOR 20A and LOR 21A are located 27 m apart on a west–east transect. In addition, two short cores were collected manually using a vibracorer, with LOSE 4 and LOSE 5 lying 15 and 30 m west of master core LOR 20A, respectively (Fig. 6C). After opening cores were cleaned and photo-documented, a description of sedimentary and pedogenic features followed on ad-hoc AG Boden (2005) KA5.

3.3.4 Laboratory analyses

The magnetic susceptibility (MS) was measured at 1 cm intervals on the core surface (LOR 20A, LOR 21A, LOSE 4 and LOSE 5) using a Bartington MS2 instrument with an MS2K surface sensor (Bartington Instruments Ltd., Witney, UK). Herewith, ferromagnetic minerals, e.g., iron oxides, as typical weathering products are detected, as well as (iron) oxides related to aerobic conditions within a fluctuating groundwater level (Evans and Heller, 2003). Slight degradation of the MS signal due to anaerobic conditions (e.g., Wang et al., 2018) are considered to be uniform across the stratigraphy for our case.

Sediment samples from representative cores (LOR 20A and LOR 21A) were extracted for grain-size analysis following the Köhn method (Köhn, 1929; DIN ISO 11277, 2002) and for measuring organic matter based on loss on ignition values at 550 °C (LOI550 °C; Blume et al., 2011). The grain-size distribution represents a proxy for the depositional environment, with fine-grained sediments associated with low-energy environments and coarse-grained sediments associated with high-energy environments. Varying values of LOI550 °C can indicate (palaeo-)surfaces and/or anaerobe conditions within a possible lake environment when LOI550 °C values are high.

Element composition for LOR 20A, LOR 21A, LOSE 4 and LOSE 5 was measured using a portable X-ray fluorescence device (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Niton XL3t GOLDD; soil mode 10 s main filter; 10 s high filter; 10 s low filter). Measurements were conducted at 2 cm vertical resolution on the surface of the cleaned cores covered by polypropylene X-ray film roll (TF-260, 6μ). Methodological issues with regard to grain-size effects, porosity or the water content for the XRF measurements are minimized by the use of element ratios instead of absolute data for single elements (e.g., Weltje and Tjallingii, 2008; Profe et al., 2016; Bertrand et al., 2024). The element ratios are used to detect syn-depositional and post-depositional changes in the sedimentary environment, and the high-resolution vertical sampling might detect thin layers for potential lake deposits. Proxies for potential lake deposits, non-perennial lake sedimentation and/or high groundwater levels are studied using log K Ti, log Ca Ti and log Rb Sr ratios.

K, Rb and Ti represent elements that are likely to be absorbed to fine-grained sediments, especially clay, where K and Rb are slightly more easily weathered than Ti (Fischer et al., 2012; Kabata-Pendias, 2010). Thus, changes in the log K Ti ratio are interpreted as grain-size proxy, with lower ratios indicating finer grain sizes. Log Ca Ti is generally seen as weathering proxy, with leaching of Ca and relative enrichment of Ti representing stronger weathering. The combination of both ratios allows us to detect masking effects, e.g., an enrichment of Ca along with constant or even increasing Ti values. Whereas a higher amount of Ca can also derive from Ca-rich allochthonous sediments, the log Rb Sr ratio can indicate autochthonous secondary carbonate precipitation, as Sr is highly absorbed to Ca (Fischer et al., 2012; Kabata-Pendias, 2010).

Selected samples from both master cores were chosen for their potential microfossils, but these yielded no findings. Numeric age control for sediment samples using radiocarbon dating is not available so far.

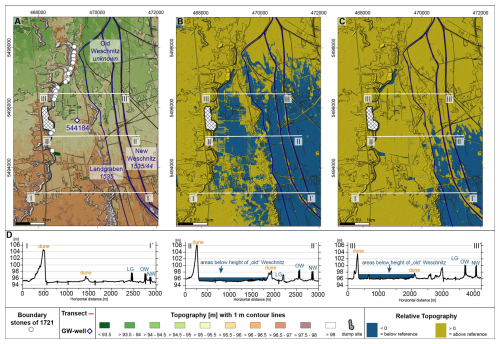

4.1 Geomorphological parameters for relative elevation models

Based on the high-resolution DEM, the spatial context for the area of Lake Lorsch in between the western and eastern dune belt becomes visible (Fig. 3A). The river Landgraben as well as the old and new courses of the river Weschnitz flow east of the smaller dune belt along a generally small topographical gradient, with decreasing altitudes towards the north. The extent of Lake Lorsch matches with an area situated between 94.5 and 95.5 m above Normalhöhennull (m NHN). Mapping of the boundary stones from 1721 CE (complemented to Schenk, 2024) marks the extent towards the northwestern part of the lake at the end of its existence.

Figure 3(A) DGM1 with 1 m contour lines for the Lake Lorsch area, mapping the boundary stones from 1721 (based on Schenk, 2024); (B) REM related to the course of the old Weschnitz; (C) REM related to the course of the new Weschnitz; (D) topographical cross-sections in the southern non-lake area (I–I′; LG 95.5 m a.s.l., OW 97.8 m a.s.l., NW 96.8 m a.s.l.), middle lake area (II–II′; LG 94.3 m a.s.l., OW 96.1 m a.s.l., NW 95.5 m a.s.l.) and northern lake area (III–III′; LG 95.9 m a.s.l., OW 94.3 m a.s.l., NW 94.3 m a.s.l.).

The old Weschnitz (the date of its construction is unknown) REM is used to illustrate the topographic relationship between the old Weschnitz and the surrounding areas as a reference level (Fig. 3B). It indicates that large areas are situated below its (current) water level. This applies to both the adjacent floodplain and the area between the dune belts. The dune itself is located above the old Weschnitz level. In comparison to the REM of the old Weschnitz, the new Weschnitz REM (Fig. 3C) has fewer areas below the elevation of the water surface, as the new Weschnitz flows at a topographic lower level. Only in the southeastern part of the study area, areas below the height of the new Weschnitz are observed.

Three topographic cross-sections (from south to north: I–I′, II–II′ and III–III′; Fig. 3D) show the relation of the watercourses Landgraben, old Weschnitz and new Weschnitz to the Lake Lorsch surroundings. In the west, each profile features a dune of 4–8 m height, with a flatter western and steeper eastern slope, which is typical for the parabolic dunes in the URG. The heights of the eastern dune belt are smaller. Whereas the southern cross-section I–I′ is just at the same topographic height as the Weschnitz channels, the middle cross-section and northern cross-section show areas that are significantly lower than the old Weschnitz channel. In comparison with the old Weschnitz, the presumed lake area lies much lower, showing height differences of up to 1.2 m in the middle and up to 1.8 m in the southern cross-section. Importantly, the elevation of the Landgraben is considerably lower compared to the old Weschnitz and similar to/just below the lake area.

4.2 (Past) groundwater levels

In April 1957, the region had some of the highest groundwater levels since extensive observations started and before groundwater extraction increased from the 1970s onwards. The area of Lake Lorsch had groundwater levels of between 0 to 0.5 m below (ground) surface (m b.s.), with some flooding in the northern part of the area (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Detail from the hydrological map series of the Hessian Rhine and Main Plain for April 1957. Editing: Wolf-Peter von Pape, HLUG, Department of Hydrogeology, Groundwater, Hessian State Office for Environment and Geology, Wiesbaden, 2013. Solid blue line: maximal extent of Lake Lorsch.

Weekly groundwater measurements at well 544184 range between 0.83 and 3.31 m b.s. for the period from 7 October 1974 to 30 December 2024 (Fig. 5). The groundwater level from April 1957 is around 0.5 m b.s. The groundwater level varies in an annual rhythm, with longer general fluctuations showing a low groundwater level (1992–1994) or higher levels (2001–2003). High groundwater levels up to 1 m below surface only exist for a short period of time with 24 data points (May–June 1983, February 1988, March 2001, January–February 2002, March 2003, June 2013). Lowest groundwater levels of 3 m below ground exist more often with 127 data points (1967, 1977, 1978, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 2022). The mean groundwater level for the entire observation period is 2.2 m b.s.

4.3 Stratigraphy

4.3.1 Geophysical prospection

The compiled ERT transect from LOR-ERT 46 and LOR-ERT 48 (Fig. 6C) has a length of 80 m and a depth of 4 m. The minimum apparent resistivity is 28.8 Ωm, whereas the maximum is 491.3 Ωm. The base of the profile in a depth of 4 to 3 m consists of low values around 35 to 50 Ωm. In the central part of the transect, these lower values reach up to 1 m b.s., covered by high resistivity of over 300 Ωm in the uppermost meter. East and west of this central part, the resistivity increases to around 100 to 200 Ωm in a depth of 3 to 1 m, followed by lower values in the uppermost meter.

Figure 6(A) Lake Lorsch on an old map from 1700 (map and description from Lepper, 1938) with emphasis on the artificial channel (Renngraben) for water input at Lake Lorsch; (B) digital elevation model and maximal extent of the lake (solid blue line) within the 94.5 to 95.5 m a.s.l. height level (semi-transparent blue area) (for the legend, see Fig. 3) with location of postulated course of the Renngraben; (C) ERT transect ERT 46/48 with location of sediment cores.

4.3.2 LOR HPT 20 and LOR HPT 21

In Fig. 7, results for the master cores derived from the DP sensing, core documentation and laboratory analyses, including grain sizes, LOI550 °C and geochemistry, are depicted, as well as MS and XRF data from short cores LOSE 4 and LOSE 5.

Figure 7Stratigraphy of sediment master cores LOR 20A and LOR 21A with results from direct push hydraulic profiling (DP-HPT), laboratory analyses (grain-size distribution, LOI, MS, log Ca Ti, Log K Ti and Log Rb Sr) and short cores LOSE 4 and LOSE 5.

Data from LOR HPT 20, logged to 2 m b.s., show a decreasing EC starting from the base with 10 to 1.9 mS m−1 at a depth of 1.15 m b.s. Between 1.15 and 1.05 m b.s., a slight increase up to 3.2 mS m−1 is followed by a strong increase up to the maximum of 10.3 mS m−1 at 0.95 m b.s. Values remain in a range of around 8 mS m−1, with a clearer decrease between 0.80 and 0.70 m b.s. down to 1.1 mS m−1. EC values are constant, with minor fluctuations up to the start of the EC log at 0.26 m b.s.

At the base of core LOR 20 between 2.00 and 1.40 m b.s., P(Corr) varies in the range of 20 to 30 kPa, with two maxima at 1.85 m b.s. (39 kPa) and at 1.58 m b.s. (45 kPa). Between 1.40 to 1.28 m b.s., P(Corr) shows a minor increase from 10 to 30 kPa, followed by a strong increase of up to 101 kPa (0.96 m b.s.) in the same depth of the EC maxima. After a short decrease to 54 kPa, there is another maximum at a depth of 0.80 m with 105 kPa, before a stronger decrease follows, comparable to the EC values to a depth of 0.70 m b.s. The maximum values for P(Corr) from LOR HPT 20 follow after 30 cm between 22 and 50 kPa in a depth between 0.38 and 0.30 m b.s. (108 to 137 kPa). The uppermost 0.3 m consists of slightly decreasing values in the range of 70 to 25 kPa.

LOR HPT 21 was logged to a depth of 1 m. The base starts with EC values of around 3 mS m−1 and shows a continuous increase up to the maximum of 16.5 mS m−1 at a depth of 0.60 m b.s. Only one minimum at 0.89 m represents a minimal decrease between 1.00 and 0.60 m b.s. EC strongly decreases in the following section from its maximum to around 5 mS m−1 at a depth of 0.50 m b.s., where minor fluctuations between 3 and 5 mS m−1 characterize the uppermost part up to a depth of 0.26 m b.s. P(Corr) from LOR HPT 21 represents in general two patterns. At the bottom of the profile, values starting from 37 kPa (1.00 m) increase up to its maximum of the whole profile at a depth of 0.66 m with 126 kPa. In between, a first maximum at a depth of 0.84 m b.s. (97 kPa) and a smaller decrease to a local minimum of 71 kPa (0.76 m b.s.) occurs. From its maximum, values strongly decrease until 0.54 m to 16 kPa, followed by a smaller decrease to the minimum of 11 kPa at a depth of 0.49 m b.s. This is followed by a second strong increase and a slightly fluctuation peak in the range of 90 to 120 kPa between a depth of 0.43 and 0.10 m b.s.

4.3.3 Sedimentological results of sediment master cores LOR 20A and LOR 21A

The stratigraphy of LOR 20A with a total length of 2 m and five sedimentary units starts at the base (unit 5) with an alternating layer of fine to medium sand and thin silt laminae between 1.89 and 1.65 m b.s. In total, grain sizes are dominated by sand with around 97 % and minor amounts of silt (1.7 %) and clay (1.3 %) resulting from the thin laminae. This unit is devoid of calcium carbonates (c0) and shows secondary iron oxides especially in the sand layers, whereas the fine silt laminae are gray. Between 1.65 m to 0.90 m b.s. (unit 4), gray-brown homogeneous sands (LOR 20A/15: 94.9 % sand; LOR 20A/14: 96.6 % sand) with patches of iron oxides and roots in the lower part of the unit are present. Calcium carbonate is absent (c0). Unit 3, between 0.89 and 0.68 m b.s., is characterized by a very dark color, a high amount of organic material (h3-4), iron concretions and scattered charcoal flakes. In particular, the lower part is slightly laminated. The grain sizes show an increased proportion of silt and clay, with up to 14 % silt and 7 % clay, representing the maximum of the entire core. This unit is capped with a brown-gray sand-dominated layer (unit 2; 0.68 to 0.37 m b.s.), a patchy gray-brown color and irregular small fragments of organic content and small roots. Clay is almost absent (0.5 % to 1.7 %), and minor amounts of silt (5.3 % to 6.5 %) complete the dominant sand component with 91.86 % to 94.25 %. The uppermost unit 1, 0.37 to 0.00 m b.s., consists of dark-brown color, slightly enhanced amounts of clay (3.8 % to 4.4 %) and silt (10 % to 11 %) and weakly rooted sand (85.2 % to 86.3 %). It represents the Ap horizon.

LOI550 °C ranges between 0.3 % and 0.7 % in unit 5 and 4, whereas unit 3 has an LOI550 °C of between 4.3 % and 5.6 % and is higher than unit 2 (0.6 % to 1 %) and unit 1 with 2.5 % to 3.3 %.

The MS in the lower units 5 and 4 is overall low, with minimally fluctuating values around 1.3 (10−5 SI). Unit 3 shows an increase in the MS from the base of the unit (0.89 m b.s.), starting at around 1.4 up to 4 (10−5 SI) at the top of the unit (0.69 m b.s.). Unit 2 shows again minor fluctuations, in this unit around 2.6 (10−5 SI), with a small increase towards the top. The highest values are found in the uppermost unit 1, with a strong increase up to a maximum MS of 127 (10−5 SI).

The results for the geochemistry show variable ratios of log Ca Ti in the lower part of the stratigraphy and a distinct increase towards higher Ca values in unit 3, before a strong decrease marks the transition to unit 2. Similarly, log K Ti shows an markable shift in unit 3, besides a general trend of lower values from the bottom to the top. Log Rb Sr has in general larger fluctuations throughout all units, but unit 3 is also characterized by minima values pointing to an increase of Sr in this unit.

Sediment core LOR 21A (1 m in length) comprises three stratigraphic units. Unit 3 consists of a yellowish-brown, calcium-carbonate-free (c0) fine and medium sand between 1.00 and 0.73 m b.s. Silt (around 6 %) and clay (around 3 %) are only minor components of the grain-size distribution. On top of this, stratigraphic unit 2 (0.73 to 0.47 m b.s.) shows a distinct shift towards finer-grained sediments, with 16 % silt and 8 % clay in the lower part of the unit up to 0.67 m b.s., and 10 % silt and up to 19 % clay in the upper part of the unit at around 0.55 m b.s. Here, a fining-upward trend is visible in the grain-size distribution. This unit shows hydromorphic features, with iron oxides as well as strong reducing conditions. A thick carbonate lens (c5) occurs at a depth of 0.62 m b.s. No sharp transition exists towards the uppermost unit of LOR 21A, starting with a smooth transition at 0.47 m b.s. upwards. A fine sand lens occurs at a depth of 0.25 m b.s., whereas the unit itself is in generally dominated by sand (around 80 %), with minor amounts of silt (14 %) and clay (6 %).

The LOI550 °C for LOR 21A shows a general increase from the base in unit 3 towards the top of unit 1. It starts with low values of 0.5 % between 1.00 and 0.78 m b.s., shows an increase with two relative maxima at a depth of 0.67 m b.s. (2.2 %) and 0.55 m b.s. (2.5 %), and a highest value at 0.36 and 0.08 m b.s., both with 3.4 %.

The MS for LOR 21A shows two distinct sections. A slight increase is observed between 1.00 and 0.75 m b.s. (1.5 to 2.5 × 10−5 SI), before a sharp increase up to 8 × 10−5 SI at 0.72 m b.s. The MS stays in this range up to 0.50 m b.s., where a sharp decrease to values of around 2.5 × 10−5 SI occur. A second sharp increase exists at a depth of 0.24 m b.s., where the maxima values of around 15 × 10−5 SI are given.

Log Ca Ti for this core exhibits constant variability apart from one large peak attributable to an increase of Ca at the base of unit 2 and one peak with enhanced K at the transition from unit 2 to 1. Log K Ti shows a continuous decrease from the base towards unit 2 and constant values for unit 1. The largest fluctuations are seen in log Rb Sr, with two significant peaks of enhanced Sr.

4.3.4 Sedimentological results of short cores LOSE 4 and LOSE 5.

Short cores LOSE 4 and LOSE 5 (Fig. 7), with a length of 1 m each, show a comparable structure of the stratigraphy. Both cores show well-sorted fine and medium sand as unit 4 at the base between 1 and 0.78 m b.s. (1 and 0.8 m b.s. at sites LOS4 and LOSE 5, respectively. These sands are free of carbonate (c0), with some spots of Fe and Mn enrichment and MS between 1 and 3 × 10−5 SI. Unit 3 (0.80 to 0.53 m b.s. LOSE 4; 0.8 to 0.62 m b.s. LOSE 5) consists of clayey fine sandy silt, showing a local maximum with a higher MS ranging from 5 to 8 × 10−5 SI. This is superimposed by a thin unit 2 consisting of carbonate-free well-sorted medium sand between 0.53 and 0.43 m b.s. (LOSE 4) and between 0.62 and 0.60 m b.s. (LOSE 5). Here, the MS shows a slight decrease in both cores. The uppermost unit 1 (0.43 to 0.06 m b.s. in LOSE 4; 0.5 to 0.12 m b.s. in LOSE 5) consists of organic-rich silty fine sand and an MS of 10 to 20 × 10−5 SI, showing the maximum of both cores. The uppermost 0.12 m b.s. in LOSE 5 and 0.06 m b.s. in LOSE 4 are lost due to sediment compaction and resulting core loss.

The geochemical proxies log Ca Ti and log K Ti show almost identical patterns in both cores. Starting from the base, log Ca Ti increases slightly in unit 4, with a distinct increase and local maxima in unit 3, followed by a sharp decrease at the boundary between unit 3 and unit 2 with a second minima. Unit 1 is characterized by increasing log Ca Ti values in both cores. Log K Ti decreases from the base of both cores towards a local minimum in unit 3, followed by an increase at the transition from unit 3 to unit 2 with a second maxima. A general trend to lower values towards the top is observed. The log Rb Sr shows the largest fluctuation across both cores, with some sharp changes at the boundaries of sedimentological units, e.g., from unit 4 to unit 3 in core LOSE 4.

The geomorphometric analyses show that the proposed area for Lake Lorsch between the two dune belts fits very well with historical sources and maps (comp. Figs. 3 and 5). The lake extent (around 3 km2) follows an area that is (currently) below the channel of the old Weschnitz. The morphometry and REM prove that only water from the old Weschnitz could be used for the water regulation of Lake Lorsch without additional damming or pumping, as the lake area is topographically lower than the old Weschnitz. Due to the low elevation of the Landgraben below the lake area, it would have needed pumping to feed water into the lake system. Although this argument is based on the current relief, these elevation differences can also be assumed for the lake phase due to the low sedimentation rate. The historical map from 1700 (from Lepper, 1938) shows that the artificial supply channel (D: “The Renngraben, which brings water into the lake”) crosses the Landgraben from 1535 with a small water bridge/canal. This is also visible in the historical map from 1690 (Fig. 2, Nikolaus Person Rheno Superior). As Lake Lorsch (1474/1479) also predates the construction of the Landgraben (1535), the Landgraben could not have been used in the initial phase of the lake. Thus, water management for Lake Lorsch was done via the old Weschnitz. The associated changes to the hydrological system are therefore examples of both embankments along channels and dams/irrigation systems during the Middle Ages as main anthropogenic activity during the phase of larger interventions on fluvial systems (Gibling, 2018).

The high groundwater level led to long-lasting surface water in the area before the construction of the canals (Schenk, 2021). Thus, historical sources on drainage of the wetlands south of Lorsch “palus laurissensis”, and the fish farming from the bailiff of Starkenburg and Lampertheimer farmers in the 14th and 15th centuries are clearly associated with a groundwater-dominated wetland, with generally higher groundwater levels in the URG during the medieval period (Tegel et al., 2020). The strong fluctuation of the log Rb Sr also points to these varying groundwater levels across time.

Two phenomena ensure that today's groundwater level is significantly lower than in the past and does not account for the time of the lake. The incision of the rivers Neckar and Rhine following major regulation measures in the early 19th century led to substantial groundwater lowering in the whole URG (Barsch and Mäusbacher, 1988; Dister et al., 1990). In addition, the modern groundwater level within the Hessische Ried has been significantly lowered due to substantial water abstraction for drinking and irrigation purposes, especially since the 1970s (Hessisches Ministerium für Umwelt, ländlichen Raum und Verbraucherschutz, 2005). Prior to this exploitation, the region had some of the highest recorded groundwater levels in the spring of 1957, which might be comparable to historical conditions before any larger water extraction since the 1970s.

Besides the long-term anthropogenic groundwater lowering over centuries, climatologically induced annual fluctuations in groundwater levels are characteristic for the region today but also very likely in the past. The lake was an artificially controlled lake during its main utilization phase. The inflows and outflows recorded in historical sources (e.g., Lepper, 1938, and historic maps within) allowed the maintenance of the lake in the long term despite annual groundwater variability and without sealing it off at the bottom. However, to what extent the lake level changes were dominated by natural processes or anthropogenic regulations remains quantitatively unknown at this point. Shallow lake conditions were ideal for carp farming, especially in summer, as carp grow best in shallow and warm waters (Oyugi et al., 2012). According to a historical map (Lepper, 1938), the deeper fish pits required for wintering were located to the east of the present-day Seehof site (Fig. 6).

The complex situation involving several drainage and supply channels, the depression of the lake itself and the relation to past groundwater levels also play an important role in the interpretation of the sedimentary sequence. Two layers – unit 3 in LOR 20A and unit 2 in LOR 21A – have important similarities but also striking differences and might be associated with the history of Lake Lorsch.

Stratigraphic unit 2 in LOR 21A shows a fining-upward sequence of sediments dominated by silt and clay, a higher EC and P(Corr) values, and enrichment in organic material. A striking feature in core LOR 21A is the distinct secondary carbonate precipitation at the depth of 0.67 m b.s., just at the significant shift in grain-size distribution between unit 2 and unit 3. These secondary carbonate features are commonly observed in the URG as an indication of distinct substrate boundaries within the groundwater fluctuation zone, called Rheinweiß (Dambeck, 2005; Engel et al., 2022). In relation to the development of groundwater levels, it is interpreted as a historical marker for higher groundwater levels. The associated fining-upward sequence of unit 2 in LOR 21A on top of this carbonate precipitation and the high amount of clay allows us to identify this unit as a potential lake deposit. This observation is also valid for unit 3 of LOSE 4 and LOSE 5, which have a similar enrichment of silt and clay with an associated higher MS, an enrichment of Ca and enriched Ti values related to clay-rich sediments.

A second possible source for the carbonate precipitation is bicarbonate (HCO) dissolved in the water. With the presence of photosynthesizing Charophyceae and aquatic plants, and their associated uptake of CO2, secondary carbonates precipitate (e.g., Bohncke and Hoek, 2007). This process is also discussed for fluvio-limnic environments in the URG (e.g., Engel et al., 2022). Here, both explanations are in good agreement with the expected sedimentological signal of Lake Lorsch and the interpretation of stratigraphic unit 2 from LOR 21A as lake deposits.

Sedimentation in unit 2 from LOR 21A seems continuous and comparable to unit 3 from LOSE 4 and LOSE 5. Due to the gradual transition towards unit 1, there seems to be no interruption of lake sedimentation, which possibly presents the silting up of the former lake. Following general sedimentation rates in natural lakes of about 1 mm a−1 (e.g., Jenny et al., 2019), the order of magnitude for deposits of Lake Lorsch with its existence for about 250 years between 1474/1479 and 1718/1720 CE is around 25 cm and fits the observations of unit 2 (LOR 21A) with a thickness of 26 cm. Therefore, we propose that even during the drainage of the lake, remnants of (shallow) lakes existed in a possibly heterogeneous spatial pattern, which is evident by the continuous sedimentation of LOR 21. If significant drainage also occurred at coring site LOR 21A, a strong intermixing of sediments, e.g., due to the use as a cattle field, would be expected. In addition, historical sources do not provide any indication as to whether the whole area was drained from time to time, or whether this phenomenon relates to specific areas of the lake, e.g., separate fishponds. However, due to the lack of chronometric age control, no sedimentation rates can be extracted. It is still open if sedimentation rates for Lake Lorsch are above average, e.g., due to eutrophication and anthropogenic water (and thus also sediment) supply, or below average, as a high sediment influx is limited due to the location outside of the Weschnitz floodplain. Hence, we can only assume that the close link between the sedimentation rates in natural lakes and the observed agreement with the detected sedimentation thickness represents a quite undisturbed setting with regard to sedimentation.

The highest amounts of clay and silt are indicative of the lowest depositional energy pointing to limnic conditions in unit 3 in LOR 20A, in accordance with higher EC and higher P(Corr) values, which indicate finer grain-sizes. Both DP proxies show the decrease in grain sizes from 0.70 to 0.80 m b.s. The lower boundary of the fine-grained sediments in the DP data are situated lower than in the core. Whereas DP data show the exact depth, coring is affected by compression and/or core loss, so the exact depth of each stratigraphic unit based on core data can be inaccurate. We interpret the slight shift for the lower boundary of unit 3 in the core at 0.90 and 0.96 m b.s. in the DP data as evidence for a compression of this unit. The log K Ti ratio also indicates finer-grained sediments associated with relative increasing Ti values related to clay-rich sediments. At the same time, the higher values of the log Ca Ti ratio indicate an enrichment of Ca in this unit in phase with the increasing amount of silt and clay. Altogether, this points to depositional conditions associated with a possible lake environment. The high LOI550 °C for this unit (absolute maximum for the whole core) and its dark color indicate very high amounts of organic input into the lake, either allochthonous or autochthonous. With the creation of the lake and the channels, a new anthropogenic carbon sink was created within the Weschnitz floodplain, which has changed the role of floodplains as ecosystem services. Although the absolute amount of altered carbon balances is relatively small on a supra-regional scale due to the size of the lake, local effects are significant because even today, the long-term balance of carbon storage is being altered by rewetting and river restoration measures (Brown et al., 2018; Maaß et al., 2021).

Striking differences in the ERT profile indicate that LOR 21A, LOSE 4 and LOSE 5, along with the lake candidate deposits, are associated with much lower resistivity values in contrast to LOR20A, which represents the central part associated with the highest resistivities of the transect. These higher values are associated with the uppermost 0.7 m from LOR 20A, showing sand-dominated sediments and, thus, higher resistivity. Below, the organic and clay- to silt-rich sediments of unit 3 from LOR 20A possibly represent the remains of the supply channel. Although unit 3 in LOR 20A has some comparable proxies for a lake candidate as in LOSE 4, LOSE 5 and LOR 20A, the organic content in the latter ones is not as high as in LOR 20A. Also, the grain size in unit 3 (supply channel candidate) from LOR 20A is slightly coarser than in unit 2 (lake candidate) from LOR 21A, which points to a slightly higher transport energy. These differences are only very small, as the supply channel also would not have any significantly greater topographic gradient as the surroundings. The significantly increased organic content in the supply channel candidate is presumably due to strong vegetation growth along the channel. We interpret these deposits as infill of this anthropogenic channel, most presumably the former Renngraben, even though the historical map from 1700 (Fig. 6A) cannot be georeferenced for exact location. The absolute height of the supply channel sediments (base at 94.16 m a.s.l.) are topographically deeper than the lake candidate deposits (base at 94.45 m a.s.l.). This indicates that the Renngraben was dug out. So far, we do not find any hints for the possible dams of the Renngraben in our stratigraphic and geophysical data.

Unit 2 from core LOR 20A could represent such backfilling of the channel (and additional cover), as the transition from unit 3 to 2 is very sharp, with unit 2 consisting of sand, organic fragments and an overall mixed character. This sharp sedimentary transition does not exist above the lake candidate unit in sediment cores LOR 21A, LOSE 4 and LOSE 5. The sandy sediment from units 1 and 2 in LOR 20A are also responsible for the high electrical resistivities in the center of the ERT transect (comp. Fig. 6C) at the former Renngraben. We suggest that this high resistivity zone depicts the extent of the former Renngraben. Electrical resistivities decrease east and west of the anomaly, thus corresponding to the lake phase in sediment cores LOR 21A, LOSE 4 and LOSE 5 (Fig. 6C).

The assumed “young” age of unit 1 from LOR 20A could also explain the sharp transition to the (modern) plow horizon and fewer pedogenic features below 0.37 m b.s.

As radiocarbon ages from unit 3 of sediment core LOR 20A are not yet available, a water supply channel of the lake phase (late 15th to early 18th century) is likely, but a drainage channel of the post-lake phase (19th to 20th century) remains possible. The repeated draining and conversion of the area since 1862 are attributed to the large-scale irrigation and drainage system (Fig. 2B) installed by the Scipio family. This adds another phase of water governance and coupling water management in the area, where competing interests and consequences to the social-hydrological system can occur (Daniell and Barreteau, 2014). The subsequent backfilling of these drainage channels occurred since the middle of the 20th century. The striking layer boundary between units 1 and 2 of LOR 20A may represent these anthropogenic interventions such as leveling. The drainage channels since the late 19th century are much smaller in comparison to the high resistivity anomaly observed in the central part of the ERT profile, thus it is more likely that our supply channel candidate represents the Renngraben channel from the lake phase. Future work will also integrate a stronger focus on the pre-lake phase, where a dominant wetland environment is suggested from historical sources. Our available sedimentary record with limited coring depth so far cannot give more details about this.

The geomorphological context of the artificial Lake Lorsch (1474/1479 to 1718/1720) points to a lake favored by a high groundwater level. This is in accordance with historical sources from the pre-lake phase, which provide indications of a landscape characterized by permanent water abundance. During the main phase for the use of the lake, information about controlled inflows and the regulation of the water level, including a complete draining of the lake, shows the ability for sophisticated water management and engineering during this time. It provides us with important insights into historical social-hydrological system changes, whose effects have lasted up to the present day. For example, the inflow to Lake Lorsch took place via the old Weschnitz, which flowed on a level topographically higher than the lake area. Furthermore, the Landgraben, which was created later and is topographically lower, had to be bridged. These structures are still visible in the landscape today. Although some of these spatial findings can also be derived from historical sources and old maps, the morphometric approach provides important additional insights into the corresponding context of the relative differences in elevation between locations. Such quantitative findings cannot be obtained from historical sources alone, just as, conversely, our findings cannot be explained without historical studies.

Our study represents an early example of strong intervention in the natural water system affecting the Weschnitz floodplain and its surroundings. However, any quantitative information to what extent natural hydrological variability or human intervention dominated or varied throughout time remains open and could be addressed with future paleohydrological modeling. Here, our results from a morphometric and sedimentological perspective serve as important input data.

The location of Lake Lorsch between the two dune belts and to the west of the former natural course of the Weschnitz means that the lake was not strongly affected by sediment-laden water during floods. We were able to identify a potential lake deposit, exhibiting characteristics indicative of a limnic environment and a high groundwater table. The supply channel deposits from core LOR 20A reflect the artificial nature of the lake, also demonstrated using the historical map with the Renngraben.

The integration of geomorphological parameters, groundwater-related proxies and a comparison with (sub-)modern groundwater levels in addition to sedimentological results helps in understanding the numerous historical traditions from an integrative landscape perspective. It reveals that the legacy of Lake Lorsch is spatially and temporally heterogeneous and characterized by a strong anthropogenic influence during and after the use of the lake. It is a phenomenon that is becoming increasingly significant in understanding an early fluvial anthroposphere. Thus, the Weschnitz floodplain and Lake Lorsch are a good example of a complex fluvial anthroposphere where humans have started to act as fluvial- and water-related agents at least 500 years before present.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon request.

The concept of the study presented in this paper was developed by FH, OB and AV. GIS investigations were done by FH. Fieldwork and laboratory analyses were carried out by PF, EA, OB, BM and AV. Research on the historical background was carried out by BJ, NH, GS, TB, RP and UR. Figures and tables for this paper were created by FH, EA and NH. All authors commented on and approved the article.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a guest member of the editorial board of E&G Quaternary Science Journal for the special issue “Floodplain architecture of fluvial anthropospheres”. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Floodplain architecture of fluvial anthropospheres”. It is not associated with a conference.

We thank Gerlinde Borngässer for laboratory work at the GEOLabor, Institute of Geography, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz. We would also like to thank Max Engel (University of Heidelberg) for his support during the fieldwork.

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the editor and reviewers for their comments, which have led to improvements in the manuscript.

This research has been supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. 509913470).

This open-access publication was funded by Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

This paper was edited by Ulrike Werban and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Ad-hoc AG Boden: Bodenkundliche Kartieranleitung, 5th edn., Schweizerbart, Hannover, 438 pp., ISBN 978-3-510-95920-4, 2005.

Appel, E., Becker, T., Wilken, D., Obrocki, L., Fischer, P., Willershäuser, T., Henselowsky, F., and Vött, A.: The Roman burgus at Trebur-Astheim and its relation to the Schwarzbach/Landgraben watercourse (Hessisches Ried, Germany) based on geophysical and geoarchaeological investigations, Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie, 20 pp., https://doi.org/10.1127/zfg/2024/0791, 2024a.

Appel, E., Becker, T., Wilken, D., Fischer, P., Willershäuser, T., Obrocki, L., Schäfer, H., Scholz, M., Bubenzer, O., Mächtle, B., and Vött, A.: The Holocene evolution of the fluvial system of the southern Hessische Ried (Upper Rhine Graben, Germany) and its role for the use of the river Landgraben as a waterway during Roman times, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 73, 179–202, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-73-179-2024, 2024b.

Barsch, D. and Mäusbacher, R.: Zur fluvialen Dynamik beim Aufbau des Neckarschwemmfächers, Berlin. Geogr. Abh., 47, 119–128, https://doi.org/10.23689/fidgeo-3194, 1988.

Bertrand, S., Tjallingii, R., Kylander, M. E., Wilhelm, B., Roberts, S. J., Arnaud, F., Brown, E., and Bindler, R.: Inorganic geochemistry of lake sediments: A review of analytical techniques and guidelines for data interpretation, Earth Sci. Rev., 249, 104639, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104639, 2024.

Blume, H.-P., Stahr, K., and Leinweber, P.: Bodenkundliches Praktikum: eine Einführung in pedologisches Arbeiten für Ökologen, insbesondere Land- und Forstwirte, und für Geowissenschaftler, 3rd edn., Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg, 255 pp., ISBN 978-3-8274-1553-0, 2011.

Bohncke, S. J. P. and Hoek, W. Z.: Multiple oscillations during the Preboreal as recorded in a calcareous gyttja, Kingbeekdal, The Netherlands, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 26, 1965–1974, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.02.017, 2007.

Bos, J. A. A., Dambeck, R., Kalis, A. J., Schweizer, A., and Thiemeyer, H.: Palaeoenvironmental changes and vegetation history of the northern Upper Rhine Graben (southwestern Germany) since the Lateglacial, Neth. J. Geosci., 87, 67–90, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016774600024057, 2008.

Brown, A. G., Lespez, L., Sear, D.A., Macaire, J.-J., Houben, P., Klimek, K., Brazier, R. E., Van Oost, K., and Pears, B.: Natural vs anthropogenic streams in Europe: History, ecology and implications for restoration, river-rewilding and riverine ecosystem services, Earth-Science Reviews, 180, 185–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.02.001, 2018.

Büttner, A. and Kautz, M.: From a dispersed medieval collection to one international library: the virtual reconstruction of the monastic library of Lorsch', Art Libraries Journal, 40, 11–20, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307472200000304, 2015.

Choinski, A., Ptak, M., and Strzelczak, A.: Examples of lake disappearance as an effect of reclamation works in Poland, Limnological Review, 12, 161–167, 2012.

Clifford, C., Bieroza, M., Clarke, S., Pickard, A., Michael J. Stratigos, M. J., Hill, M. J., Raheem, N., Tatariw, C., Wood, P. J., Arismendi, I., Audet, J., Aviles, D., Bergman, J. N., Brown, A. G., Burns, E. A. Connolly, J., Cook, S., Crabot, J., Cross, W. F., Dean, J. F., Evans, C. D., Fenton, O., Friday, L., Gething, K. J., Guillermo Giannico, G., Wahaj Habib, W., Eliza Maher Hasselquist, E. M., Nathaniel, M., Heili, N. M., van der Knaap, J., Kosten, S., Law, A., van der Lee, G. H., Mathers, K. L., Morgan, J. E., Rahimi, H., Sayer, C. D., Schepers, M., Shaw, R. F., Smiley Jr., P. C., Speir, S. L., Strock, J. S., Struik, Q., Tank, J. L., Wang, H., Webb, J. R., Webster, A. J., Yan, Z., Zivec, P., and Peacock, M.: Lines in the landscape, Commun. Earth Environ., 6, 693, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02699-y, 2025.

Codex Laureshamensis, edited by: Glöckner, K., Karl Glöckner, 3 Vol. (Darmstadt 1929/1933/1936).

Dambeck, R.: Beiträge zur spät- und postglazialen Fluss- und Landschaftsgeschichte im nördlichen Oberrheingraben, PhD thesis, University of Frankfurt/Main, Germany, urn:nbn:de:hebis:30-0000009080, 2005.

Dambeck, R. and Bos, J. A. A.: Lateglacial and Early Holocene landscape evolution of the northern Upper Rhine River valley, south-western Germany, Z. Geomorph. Suppl., 128, 101–127, 2002.

Dambeck, R. and Thiemeyer, H.: Fluvial history of the northern Upper Rhine River (southwestern Germany) during the Lateglacial and Holocene times, Quaternary Int., 93–94, 53–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-6182(02)00006-X, 2002.

Daniell, K. A. and Barreteau, O.: Water governance across competing scales: Coupling land and water management, Journal of Hydrology, 519, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.10.055, 2014.

Di Baldassarre, G., Kooy, M., Kemerink, J. S., and Brandimarte, L.: Towards understanding the dynamic behaviour of floodplains as human-water systems, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 3235–3244, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-17-3235-2013, 2013.

DIN ISO 11277: Bodenbeschaffenheit – Bestimmung der Partikelgrößenverteilung in Mineralböden – Verfahren mittels Siebung und Sedimentation, 38 pp., https://doi.org/10.31030/9283499, 2002.

Dister, E., Gomer, D., Obrdlik, P., Petermann, P., and Schneider, E.: Water management and ecological perspectives of the upper Rhine's floodplains, Regul. River., 5, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/rrr.3450050102, 1990.

Engel, M., Henselowsky, F., Roth, F., Kadereit, A., Herzog, M., Hecht, S., Lindauer, S., Bubenzer, O., and Schukraft, G.: Fluvial activity of the late-glacial to Holocene “Bergstraßenneckar” in the Upper Rhine Graben near Heidelberg, Germany – first results, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 71, 213–226, https://doi.org/10.5194/egqsj-71-213-2022, 2022.

Evans, M. and Hellers, F.: Environmental Magnetism Principles and Applications of Enviromagnetics, International Geophysics Volume 86, Academic Press/Elsevier Science & Technology, 299 pp., ISBN 0122438515, 2003.

Fecher, M.: Die Namen der Gemarkungen Kleinhausen und Seehof (Hessisches Flurnamenbuch Band 24), Elwert, Gießen, 79 pp., 1942.

Fischer, P., Hilgers, A., Protze, J., Kels, H., Lehmkuhl, F., and Gerlach, R.: Formation and geochronology of Last Interglacial to Lower Weichselian loess/palaeosol sequences – case studies from the Lower Rhine Embayment, Germany, E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 61, 48–63, https://doi.org/10.3285/eg.61.1.04, 2012.

Fischer, P., Wunderlich, T., Rabbel, W., Vött, A., Willershäuser, T., Baika, K., Rigakou, D., and Metallinou, G.: Combined Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT), Direct-Push Electrical Conductivity (DP-EC) Logging and Coring – A New Methodological Approach in Geoarchaeological Research, Archaeological Prosepction, 23, 213–228, https://doi.org/10.1002/arp.1542, 2016.

Gegg, L., Jacob, L., Moine, O., Nelson, E., Penkman, K. E. H., Schwahn, F., Stojakowits, P., White, D., Ulrike Wielandt-Schuster, U., and Preusser, F.: Climatic and tectonic controls on deposition in the Heidelberg Basin, Upper Rhine Graben, Germany, Quat. Sci. Rev., 345, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.109018, 2024.

Geoprobe Systems: Geoprobe Hydraulic Profiling Tool (HPT) System, Standard Operating Procedure, Tech. Bull., MK3137, 22 pp., 2015.

Gibling, M. R.: River Systems and the Anthropocene: A Late Pleistocene and Holocene Timeline for Human Influence, Quaternary, 1, 21, https://doi.org/10.3390/quat1030021, 2018.

Hanel, N.: Ein römischer Kanal zwischen dem Rhein und Groß-Gerau?, Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 25, 107–116, 1995.

Heising, A.: Der Schiffslände-Burgus von Trebur-Astheim: Schicksal einer Kleinfestung in Spätantike und frühem Mittelalter, in: Das Gebaute und das Gedachte: Siedlungsform, Architektur und Gesellschaft in prähistorischen und antiken Kulturen, edited by: Raeck, W. and Steuernagel, D., Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt, Bonn, 151–166, 2012.

Helfert, M.: Die Weschnitz und die ecclesia sancti Petri. Zur Gründung des Klosters in Lorsch im frühen Mittelalter und zur topographischen Lage des sogenannten Altenmünsters, in: Lege artis: Festschrift für Hans-Markus von Kaenel, edited by: Kemmers, F., Maurer, T., and Rabe, B., Verlag Dr. R. Habelt GmbH, Bonn, 99–117, 2014.

Henselowsky, F., Becker, T., Bubenzer, O., Mächtle, B., Schenk, G. J., and Vött, A.: Wechselbeziehungen zwischen der Flusslandschaft der Weschnitz und dem Kloster Lorsch, in: HessenArchäologie. Jahrbuch Für Archäologie und Paläontologie in Hessen, edited by: Recker, U., 294–299, ISBN 978-89822-254-6, 2024.

Hessisches Landesamt für Naturschutz, Umwelt und Geologie (HLNUG): Lorsch Weschnitz Gewässerdurchfluss Tagesmittelwerte, Messstellennummer 23942300, https://www.hlnug.de/static/pegel/wiskiweb3/webpublic/#/overview/Wasserstand/station/41276/Lorsch/download (last access: 4 June 2025), 2025.

Hessisches Ministerium für Umwelt, ländlichen Raum und Verbraucherschutz (Ed.): Das Hessische Ried. Zwischen Vernässung und Trockenheit: eine komplexe wasserwirtschaftliche Problematik, Wiesbaden, 70 pp., https://doi.org/10.1201/b10158, 2005.

Hillmus, N.: Kunde für den Landesherren. Berichte von Kosten und Nutzen menschlicher Eingriffe in Flusslandschaften zu Gedeih und Verderb der Anwohner des Lorscher Sees in der frühneuzeitlichen Kurpfalz, in: Flusslandschaften im Wandel. Kleine multidisziplinäre Quellenkunde der Fluvialen Anthroposphäre, edited by: Schenk, G. J. and Hillmus, N., TUprints, Darmstadt, 212–221, https://doi.org/10.26083/tuprints-00030117, 2025.

Holzhauer, I., Kadereit, A., Schukraft, G., Kromer, B., and Bubenzer, O.: Spatially heterogeneous relief changes, soil formation and floodplain aggradation under human impact – geomorphological results from the Upper Rhine Graben (SW Germany), Z. Geomorph., 61, 121–158, https://doi.org/10.1127/zfg_suppl/2017/0357, 2017.

Hoselmann, C.: The Pliocene and Pleistocene fluvial evolution in the northern Upper Rhine Graben based on results of the research borehole at Viernheim (Hessen, Germany), E&G Quaternary Sci. J., 57, 286–314, https://doi.org/10.3285/eg.57.3-4.2, 2009.

Jenny, L., Koirala, S., Gregory-Eaves, I., Francus, P., Niemann, C., Ahrens, B., Brovkin, V., Baud, A., Ojala, A. E. K., Normandeau, A., Zolitschka, B., and Carvalhais, N.: Human and climate global-scale imprint on sediment transfer during the Holocene, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 22972–22976, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908179116, 2019.

Kabata-Pendias, A.: Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 4th edn., CRC Press, Boca Raton, 520 pp., 2010.

Kneisel, C.: Electrical resistivity tomography as a tool for geomorphological investigations – some case studies, Z. Geomorph. Suppl., 132, 37–49, 2003.

Köhn, M.: Korngrößenbestimmung mittels Pipettanalyse, Tonind.-Ztg., 55, 729–731, 1929.

Koob, F.: Die Weschnitz und ihre Probleme in den vergangenen Jahrhunderten, Verlag der Südhessischen Post, Heppenheim, 83 pp., 1956.

Lepper, C.: Seehof. Geschichte eines verschwundenen Dorfes, Verlag Stadtbibliothek, Worms, 105 pp., 1938.

Loke, M. H. and Barker, R. D.: Rapid Least-Squares Inversion of apparent resistivity pseudosections by a quasi-Newton method, Geophys. Prospect., 44, 131–152, 1996.

Maaß, AL., Schüttrumpf, H., and Lehmkuhl, F.: Human impact on fluvial systems in Europe with special regard to today's river restorations, Environ. Sci. Eur., 33, 119, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-021-00561-4, 2021.

Mangold, A.: Die alten Neckarbetten in der Rheinebene, Abh. Großherzogl. Hess. Geol. Landesanst. Darmstadt, 2, 75–114, 1892.

McCall, W.: Application of the Geoprobe HPT Logging System for Geo-Environmental Investigations, Geoprobe Tech. Bull., MK3184, 1–36, 2011.

Noack, W.: Landgraf Georg I. von Hessen und die Obergrafschaft Katzenelnbogen (1567–1596), Historischer Verein für Hessen, Darmstadt, 242 pp., 1966.

Olson, P. L., Legg, N. T., Abbe, T. B., Reinhart, M. A., and Radloff, J. K.: A Methodology for Delineating Planning-Level Channel Migration Zones, Washington State Department of Ecology, Publication no. 14-06-025, 83 pp., 2014.

Oyugi, D. O., Cucherousset, J., Baker, D. J., and Britton, J. R.: Effects of temperature on the foraging and growth rate of juvenile common carp, Cyprinus carpio, Journal of Thermal Biology, 37, 89–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2011.11.005, 2012.

Pflanz, D., Kunz, A., Hornung, J., and Hinderer, M.: New insights into the age of aeolian sand deposition in the northern Upper Rhine Graben (Germany), Quaternary Int., 625, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.03.019, 2022.

Platz, M. M.: Von Römern, Turmschädeln und Klosterruinen. Befunde und Funde vom Seehof, in: Kloster Lorsch. Vom Reichskloster Karls des Großen zum Weltkulturerbe der Menschheit, edited by: Zeeb, A., Pinsker, B., zu Erbach-Schönberg, M., and Untermann, M., 126–133, 2011.

Prien, R., Appel, E., Becker, T., Bubenzer, O., Fischer, F., Mächtle, B., Willershäuser, T., and Vött, A.: A Roman Fortlet and Medieval Lowland Castle in the Upper Rhine Graben (Germany): Archaeological and Geoarchaeological Research on the Zullestein Site and the Fluvioscape of Lorsch Abbey, Heritage, 8, 180, https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050180, 2025.

Profe, J., Zolitschka, B., Schirmer, W., Frechen, M., and Ohlendorf, C.: Geochemistry unravels MIS 3/2 paleoenvironmental dynamics at the loess–paleosol sequence Schwalbenberg II Germany, Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol., 459, 537–551, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.07.022, 2016.

Rabiger-Völlmer, J., Schmidt, J., Linzen, S. Schneider, M., Werban, U., Dietrich, P., Wilken, D., Wunderlich, T., Fediuk, A., Berg, S., Werther, L., and Zielhofer, C.: Non-invasive prospection techniques and direct push sensing as high-resolution validation tools in wetland geoarchaeology – Artificial water supply at a Carolingian canal in South Germany?, Journal of Applied Geophysics, 173, 103928, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jappgeo.2019.103928, 2020.

Rösch, N.: Die Rheinbegradigung durch Johann Gottfried Tulla, Zfv – Zeitschrift für Geodäsie Geoinformation und Landmanagement, 4, 242–248, 2009.

Schefers, H.: Das Kloster Lorsch, in: Die geistlichen Territorien und die Reichsstädte, Handbuch der hessischen Geschichte 7, edited by: Gräf, H. T. and Jendorff, A., Marburg, 191–266, ISBN 978-3942225571, 2023.

Schenk, G. J.: Lorsch und das Wasser, in: Laureshamensia. Forschungsberichte des Experimentalarchäologischen Freilichtlabors Karolingischer Herrenhof Lauresham, 3, 34–57, ISSN 3053-5700, 2021.

Schenk, G. J.: Lorsch and the Weschnitz Floodplain. Questions about the Long History of Resource Use and Conflicts of Use on the Way to a “Fluvial Anthroposphere” (8th–18th century), in: Conflicts over Water Management and Water Rights from the end of Antiquity to Industrialisation, edited by: Campopiano, M. and Schenk, G. J., 159–187, ISBN 978-3-515-13724-9, 2024.

Slaughter, S. L. and Hubert, I. J.: Geomorphic Mapping of the Chehalis River Floodplain, Cosmopolis to Pe Ell, Grays Harbor, Thurston, and Lewis Counties, Circular 118, 59 pp. map book, scale 1 : 28 000 and 2 pp. text, Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Information, Washington, 2014.

Tarolli, P., Cao, W., Sofia, G., Evans, D., and Ellis, E.: From features to fingerprints: A general diagnostic framework for anthropogenic geomorphology, Progress in Physical Geography, 43, 95–128, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133318825284, 2019.

Tegel, W., Seim, A., Skiadaresis, G., Ljungqvist, F. C., Kahle, H.-P., Land, A., Muigg, B., Nicolussi, K., and Büntgen, U.: Higher groundwater levels in western Europe characterize warm periods in the Common Era, Sci. Rep., 10, 16284, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73383-8, 2020.

Wang, J.-S., Grimley, D. A., Yu, C., and Dawson, J. O.: Soil magnetic susceptibility reflects soil moisture regimes and the adaptability of tree species to these regimes, Forest Ecology and Management, 255, 1664–1673, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.11.034, 2018.

Weltje, G. J. and Tjallingii, R.: Calibration of XRF core scanners for quantitative geochemical logging of sediment cores: Theory and application, Easrt and Planetary Science Letters, 274, 423–438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2008.07.054, 2008.

Werther, L., Mehler, N., Schenk, G. J., and Zielhofer, C.: On the way to the Fluvial Anthroposphere – Current limitations and perspectives of multidisciplinary research, Water, 13, 2188, https://doi.org/10.3390/w13162188, 2021.

Wirsing, G. and Luz, A.: Hydrogeologischer Bau und Aquifereigenschaften der Lockergesteine im Oberrheingraben (Baden-Württemberg), vol. 19, LGRB Informationen, 2007.